PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — It may seem odd at first glance — the first democratically elected president here, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, returning from exile on Friday, days before Haiti’s elections, after a vow not to insert himself in its democracy.

News Analysis

Not on the Ballot, but on All Minds in Haiti

By RANDAL C. ARCHIBOLD

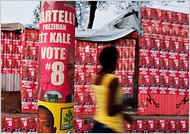

Shannon Stapleton/Reuters

Campaign posters for Michel Martelly, one of Haiti's presidential candidates.

Related

-

Just Days Before Election, Aristide Returns to Cheers and Uncertainty in Haiti (March 19, 2011)

-

Times Topic: Jean-Bertrand Aristide

There is, of course, debate over whether Mr. Aristide has already inserted himself through his very return. He received a celebratory welcome from hundreds, if not thousands, of supporters who overran his home and made it clear that his cult of personality, particularly among the poor who make up the majority here, remained strong.

Upon arriving after seven years of exile in South Africa, he also promptly took a swipe at the exclusion of his political party, over a technical matter, from the presidential election, which is culminating in a runoff on Sunday.

But whether Mr. Aristide eventually backs down from the stated reason for his return — to work on social causes like education in a country still battered by the earthquake last year — his re-emergence carries its own risks and obstacles, along with the obvious rewards.

“I think whether he means it or not, he really is a political figure, and there is no way he can avoid being a part of politics,” said Robert Fatton, a professor at the University of Virginia and the author of two books on Haitian political history.

“Too many social forces want to use him or depend on him,” he added. “He is almost condemned to be a political figure.”

Many of the people who massed at his home on Friday said they were waiting for cues from Mr. Aristide on whom to vote for.

Some wondered whether his comments about the exclusion of his former party, Fanmi Lavalas, were a coded message to stay home, the kind of disruption feared by American officials, who worked feverishly to keep Mr. Aristide out of the country before Sunday.

Such is his power, or fear of it, that the two presidential candidates, Mirlande Manigat, a former first lady with establishment ties, and Michel Martelly, a popular singer running as a populist, both set aside their past opposition to Mr. Aristide for a softer line.

Analysts agreed that Mr. Martelly had more to lose. His base of the young, disaffected poor parallels Mr. Aristide’s, and his appearances — in an echo of Mr. Aristide’s headiest days — draw the largest, most passionate crowds, though it is unclear how many of those followers have registered to vote.

Still, no matter who wins, Mr. Aristide confronts a political landscape that has drastically changed since he left for exile in 2004, facing pressure from American diplomats and an uprising that threatened to topple him.

Mr. Aristide had been ousted once before, in 1991, just months after an election he won largely on the strength of his longtime efforts to end the Duvalier family dictatorship. He was restored in 1994 with the help of 20,000 American troops.

Alex Dupuy, a Wesleyan University sociologist who wrote “The Prophet and Power: Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the International Community, and Haiti,” said Mr. Aristide’s former party was now in tatters, riven by internal discord and with no members in Parliament. Some former members have joined other parties.

“He would have to rebuild that party, and that would be a daunting task,” Mr. Dupuy said.

It is also unclear why Mr. Aristide would take on that job. Technically, the Constitution bars Mr. Aristide from a third term. But as his enthusiasts here and abroad have noted, he did not complete his last term, raising thorny legal questions over whether he would have the right to run again in five years. His arrival now appears to be satisfying one requirement, that a presidential candidate live in the country for five years before the campaign begins.

Still, in a country exhausted by disaster and political strife, Mr. Aristide may also choose to play spoiler or kingmaker from the sidelines, even if it means using subtle gestures or statements. “He is going to have to tread carefully to not ruffle the nest, because who knows what they could come back with against him,” Mr. Dupuy said.

When Mr. Aristide left in 2004, allegations of corruption and associates’ ties to drug trafficking swirled around his administration, tarnishing his image as an up-with-the-poor reformer and helping to fuel the rebellion against him. He was also accused of orchestrating armed gangs to intimidate opponents.

“He is unlikely to cause trouble, because he does not really know what people think of him and does not want legal trouble or lawsuits for damages,” said Henry Carey, a political scientist at Georgia State University who studies Haiti. “He probably feels he needs to redeem his democratic credentials and reputation.”

The what-does-he-really-want questions will no doubt carry on for some time, with predictions particularly perilous here. Mr. Aristide’s nemesis, Jean-Claude Duvalier, the former dictator known as Baby Doc, returned suddenly here in January and is living quietly under threat of a criminal case.

“Haiti is unpredictable,” Mr. Fatton said. “If you told me a few months ago Aristide and Duvalier would be sharing the same soil I would have told you, no, you’re crazy.”

Copyright 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Sunday, March 20, 2011.