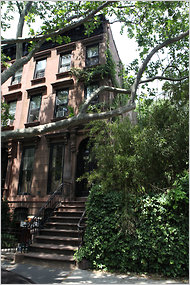

When Mildred Furiya moved to a 19th-century town house on State Street in Brooklyn from a cramped walkup in Greenwich Village in 1967, a boarding house known for prostitution stood across a barren street, groups of unemployed men hung out on the corner and the Brooklyn House of Detention was a defining presence a block away. Standing in the garden — which functioned as a garbage dump for the apartment building next door — her husband, George, was almost hit in the head by a plaster Madonna statue someone had thrown from a window.

The Appraisal

Her $16,000 Town House, Now Available for Just $1.879 Million More

Mildred Furiya, 89, bought her town house at 299 State Street in Brooklyn in 1966. It cost $16,000.

By DIANE CARDWELL

The jail, on hiatus from housing inmates, still looms over State Street, but Mrs. Furiya’s block, between Smith and Hoyt Streets, is much changed.

Sunlight filters through the trees, the unemployed men are long gone and the boarding house prostitutes have given way to middle-class and affluent families. The apartment building that once abutted Mrs. Furiya’s Italianate brownstone, which was declared a city landmark in 1973, is now a parking lot slated for nine new town houses, siblings to a row of 14 down the block that were among the first to sell for more than $2 million in Downtown Brooklyn.

And now Mrs. Furiya, 89, says the time has come for her to sell as well. Mr. Furiya died in 1994, her daughters have homes of their own, and she would like to live more simply: an apartment in the neighborhood or on the Upper East Side, perhaps, a place where she could walk around at night. She has also grown accustomed to being near the subway she rides to the classes in Sanskrit that help keep her mind agile and her outlook on life positive.

Given how values have climbed in the area, she said, “I knew I could be provided for by selling the house and how it could benefit the children.”

It is the gentrifier’s holy grail: a fixer-upper in a marginal area with potential. After the renovations, the lobbying for community improvements with like-minded neighbors, the holding on through the ups and downs, the scrappy, savvy buyer trades it in for a bigger, better place — or cashes out and retires in luxury.

It happens all the time in New York, but not usually at as high a level as at 299 State Street, in part because Mrs. Furiya held on so long. She bought the house for $16,000 in 1966 with a cash gift from her father, the economist Alvin H. Hansen; her brokers, Ross Brown and Florence Ng of Citi Habitats, plan to list the house at about $1.895 million. A sale at that price would represent an increase of nearly 12,000 percent over 45 years — or an annual return of about 11 percent.

And that kind of increase does not happen everywhere. It is often in neighborhoods with fast access to Manhattan’s business districts, helped along by forces like rezonings and redevelopment plans, said Jonathan J. Miller, president of Miller Samuel, an appraisal and consulting company.

This has been the case in the neighborhood, where property owners have benefitted from proximity to the BAM Cultural District, the rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn and the redevelopment of land around Mrs. Furiya’s house through a public-private partnership that brought in the new town houses and a mixed-use building with subsidized apartments, performance spaces and social services.

For Mrs. Furiya and her husband, the neighborhood’s potential was clear, she said, abutting both affluence and poverty, with excellent public transportation and within walking distance of good private schools. But the public schools left something to be desired, so she made sure her daughters would be able to stay at Public School 41 in the Village before the purchase. For her husband, an electrical engineer who had studied architecture but was planning to live with sumo wrestlers in Japan as research for a novel he had in mind, the house became his creative project instead.

Over the years, the Furiyas scraped layers of paint off a half-dozen marble mantles, refinished the floors, laid slate tile in the kitchen and made a garden out back with gray stone walkways, bamboo, and a large, productive apple tree.

They were active in the neighborhood, she said, helping ward off the widening of Atlantic Avenue, encouraging the designation of the 19th-century town houses on the block as landmarks, and making friends with the other families and creative types — including a drama professor and a stage manager for “Hair,” she said.

They quickly came to look upon the unemployed men on the corner as a built-in security force, a version of what Jane Jacobs called “eyes on the street.”

“They were what some would call bums on the street, but they were more welcome than anyone to be here,” Mrs. Furiya said. “We realized we were lucky. No one was getting mugged walking from Flatbush to Court.”

There were inevitable stresses and conflicts, with political battles among neighbors, and couples divorcing, Mrs. Furiya said. Eventually, the original homesteaders began to sell and move away, often to be replaced by people who could afford to pay for their renovations all at once. One man, a poet, who had planned to put a loft bed over his front parlor door, never finished his house because a troubled relative stabbed him on State Street.

Now, Mrs. Furiya is hopeful that another buyer will see in the house what she and her husband saw so many years ago: a diamond in the rough — albeit far less rough this time around.

“We live in New York, we live here adjusting, adapting, hearts hurting, helping, ignoring — everything we do to live here,” she said. “On this block it all happened, from the best to the most tragic.”