Washington

Economic Scene

Why Budget Cuts Don’t Bring Prosperity

By DAVID LEONHARDT

Remember the German economic boom of 2010?

Germany’s economic growth surged in the middle of last year, causing commentators both there and here to proclaim that American stimulus had failed and German austerity had worked. Germany’s announced budget cuts, the commentators said, had given private companies enough confidence in the government to begin spending their own money again.

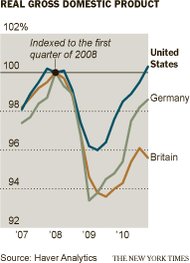

Well, it turns out the German boom didn’t last long. With its modest stimulus winding down, Germany’s growth slowed sharply late last year, and its economic output still has not recovered to its prerecession peak. Output in the United States — where the stimulus program has been bigger and longer lasting — has recovered. This country would now need to suffer through a double-dip recession for its gross domestic product to be in the same condition as Germany’s.

Yet many members of Congress continue to insist that budget cuts are the path to prosperity. The only question in Washington seems to be how deeply to cut federal spending this year.

If the economy were at a different point in the cycle — not emerging from a financial crisis — the coming fight over spending could actually be quite productive. Republicans could force Democrats to make government more efficient, which Democrats rarely do on their own. Democrats could force Republicans to abandon the worst of their proposed cuts, like those to medical research, law enforcement, college financial aid and preschools. And maybe such a benevolent compromise can still occur over the next several years.

The immediate problem, however, is the fragility of the economy. Gross domestic product may have surpassed its previous peak, but it’s still growing too slowly for companies to be doing much hiring. States, of course, are making major cuts. A big round of federal cuts will only make things worse.

So if the opponents of deep federal cuts, starting with President Obama, are trying to decide how hard to fight, they may want to err on the side of toughness. Both logic and history make this case.

Let’s start with the logic. The austerity crowd argues that government cuts will lead to more activity by the private sector. How could that be? The main way would be if the government were using so many resources that it was driving up their price and making it harder for companies to use them.

In the early 1990s, for instance, government borrowing was pushing up interest rates. When the deficit began to fall, interest rates did too. Projects that had not previously been profitable for companies suddenly began to make sense. The resulting economic boom brought in more tax revenue and further reduced the deficit.

But this virtuous cycle can’t happen today. Interest rates are already very low. They’re low because the financial crisis and recession caused a huge drop in the private sector’s demand for loans. Even with all the government spending to fight the recession, overall demand for loans has remained historically low, the data shows.

Similarly, there is no evidence that the government is gobbling up too many workers and keeping them from the private sector. When John Boehner, the speaker of the House, said last week that federal payrolls had grown by 200,000 people since Mr. Obama took office, he was simply wrong. The federal government has added only 58,000 workers, largely in national security, since January 2009. State and local governments have cut 405,000 jobs over the same span.

The fundamental problem after a financial crisis is that businesses and households stop spending money, and they remain skittish for years afterward. Consider that new-vehicle sales, which peaked at 17 million in 2005, recovered to only 12 million last year. Single-family home sales, which peaked at 7.5 million in 2005, continued falling last year, to 4.6 million. No wonder so many businesses are uncertain about the future.

Without the government spending of the last two years — including tax cuts — the economy would be in vastly worse shape. Likewise, if the federal government begins laying off tens of thousands of workers now, the economy will clearly suffer.

That’s the historical lesson of postcrisis austerity movements. The history is a rich one, too, because people understandably react to a bubble’s excesses by calling for the reverse. When Franklin Roosevelt was running for president in 1932, he repeatedly called for a balanced budget.

But no matter how morally satisfying austerity may be, it’s the wrong answer. Hoover’s austere instincts worsened the Depression. Roosevelt’s postelection reversal helped, but he also prolonged the Depression by raising taxes and cutting spending in 1937. Only the giant stimulus program known as World War II finally ended the Depression. When the private sector is hesitant to spend, the government has to — or no one will.

Our recent crisis serves up the same lesson. Germany isn’t even the best example. Its response to the crisis has had some successful features, like an hours-reduction program to minimize layoffs, and Germany’s turn to austerity has not been radical. Britain’s has been radical, with a tax increase having already taken effect and deep spending cuts coming. Partly as a result, Britain’s economy is now in worse shape than Germany’s.

“It’s really quite striking how well the U.S. is performing relative to the U.K., which is tightening aggressively,” says Ian Shepherdson, a Britain-based economist for the research firm High Frequency Economics, “and relative to Germany, which is tightening more modestly.” Mr. Shepherdson adds that he generally opposes stimulus programs for a normal recession but that they are crucial after a crisis.

The trick is finding the political will to end the stimulus when the time comes. That is not easy, especially for Democrats, given that stimulus programs tend to include policies they favor. But the wave of recently elected Republicans, in Congress and the states, will no doubt be happy to help summon that political will.

For the sake of the economy, the best compromise in coming weeks would be one that trades short-term spending for medium- and long-term cuts. Beef up the cost-control measures in the health care overhaul and add new ones, like malpractice reform. Cut more wasteful military programs, like the F-35 jet engine. Force more social programs to prove they work — and cut their funding in future years if they don’t.

By all means, though, don’t follow the path of the Germans and the British just because it feels morally satisfying.