What’s the debt ceiling?

The legal limit on borrowing by the federal government. Before 1917, Congress had to approve borrowing each time it came up. In order to allow for more flexibility as the nation entered World War I, lawmakers agreed to give the federal government blanket approval for most types of borrowing — as long as the total was less than an established limit.

|

Why is this an issue now?

The nation’s debt is inching closer to the legal limit of $14.3 trillion. According to

Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner, the ceiling could be breached as soon as May 16, though the government could take unconventional measures such as halting contributions to pension funds to delay that point until July 8.

What happens if the debt ceiling is breached?

If Congress does not increase the limit, borrowed funds would not be available to pay bills and the United States may be forced to default on its debt obligations. There’s no precedent for this situation. Treasury has never been unable to make payments as a result of reaching the debt limit. With a fragile global recovery counting on U.S. economic stability, the debt limit issue could roil international financial markets. Democrats and Republicans agree that if the debt limit is not raised we would be inviting economic catastrophe.

So if both parties agree, why not just raise the limit? What is everyone arguing about?

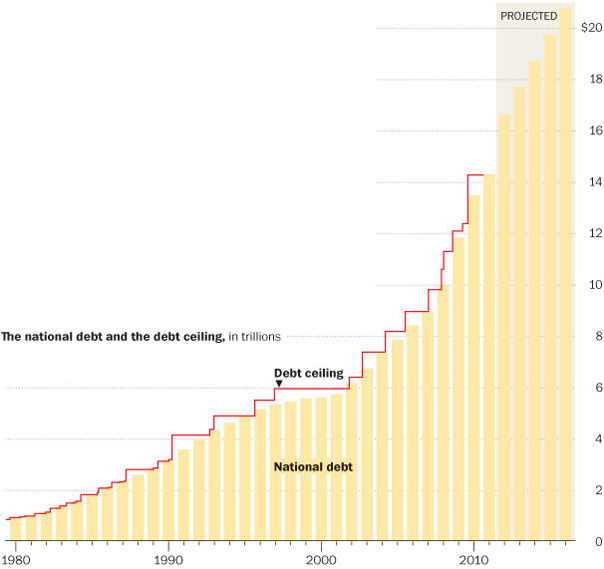

In the past, raising the debt ceiling has mostly been a perfunctory matter. The ceiling has been raised almost 100 times since it was established and has gone from less than $1 trillion in the 1980s to $6 trillion in the 1990s. The most recent time the ceiling was boosted was in February 2010. Legislation to raise the debt limit usually prompts partisan posturing about fiscal responsibility, but little real drama. This time is different.

With the national debt at its highest point in 50 years compared with the size of the U.S. economy, the debate about the ceiling has become entwined in the larger issue about slashing the budget. The budget debate is shaping up around trying to balance two perhaps equally unpopular remedies: sharp cuts to popular government-funded programs and major tax increases. Republican lawmakers say that if they raise the limit they need a commitment from the White House for more spending cuts. The Obama administration has resisted the idea of including spending caps or other budget-process reforms in legislation to raise the debit ceiling, arguing that ensuring the government’s solvency is too important to be held hostage to other issues.

How much money are we talking about?

Under the spending plan President Obama submitted to Congress in February, lawmakers would have to raise the limit by nearly $2.2 trillion just to see the nation through next year. Under the more austere blueprint that House Republicans approved last week, the government would require about $1.9 trillion in fresh debt by October 2012 — a month before the next presidential election.

Why does the United States have so much debt anyway?

There are numerous reasons. Here are some major ones: Under President George W. Bush, the national debt soared to $4.36 trillion because of the cost of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and new tax cuts, and again under Obama, an additional $3.9 trillion, because of the economic stimulus and decreased tax revenue during the recession.

The Washington Post Company