| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted April 3, 2004 |

Taking the Liberalism out of Liberal Arts |

| ___________ |

By YILU ZHAO |

| ___________ |

City halls where gay marriage vows are uttered, the Superbowl half-time show and movie theaters showing "The Passion of the Christ" would seem to be prime battlegrounds in the latest culture wars. But to conservative crusaders like David Horowitz, the main action is still on college campuses, which he insists have been colonized by "tenured leftists" and turned into "their political base."

|

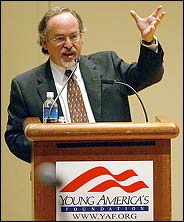

AP Photo |

| David Horwitz, a conservative author who has written a "bill of rights for academics, speaking at Brown University last October. |

So Mr. Horowitz, author of "Left Illusions: An Intellectual Odyssey" (Spence Publishing, 2003) and the president of the Center for the Study of Popular Culture, is spearheading a campaign to end what he calls discrimination against conservative faculty and students. At its core is an "academic bill of rights," written by Mr. Horowitz, that asks universities, among other things, to include both conservative and liberal viewpoints in their selection of campus speakers and syllabuses for courses and to choose faculty members "with a view toward fostering a plurality of methodologies and perspectives."

The campaign, which is resurrecting the disputes that characterized the culture wars' first wave in the 1980's, has caught the attention of Republican legislators and conservative student groups, much to the chagrin of many university administrators and faculty members. On March 23 the Georgia Senate passed a nonbinding resolution almost identical to the bill of rights drawn up by Mr. Horowitz, who had flown in to testify before the senators on liberal bias. In mid-March a similar bill was withdrawn from the Colorado legislature after the presidents of four universities, including the University of Colorado, agreed to publicize their grievance policies on campus and pledged to make their institutions open to all political viewpoints.

|

|||

| A 'bill of rights' for conservative scholars. | |||

| _______________ |

| A 'bill of rights' |

Meanwhile, Jack Kingston, a Republican congressman from Georgia, has introduced Mr. Horowitz's bill as a nonbinding resolution in the House of Representatives.

"We are only trying to get their attention," Mr. Horowitz said, referring to university administrations. He said he was turning to legislative lobbying only as a last resort, after having waited unsuccessfully for a year for the State University of New York to adopt his bill of rights. "I am using the legislative resolutions as an inducement to have universities look into this. I have no intention of going to Congress to impose a politically correct faculty on a university."

"Some people have no problem to have the government come in to meddle on the basis of skin color," he added.

The bill, he says, is based on the tradition of academic freedom, but many scholars argue that the legislative approach adopted by him and his followers could erode the very freedom the bill champions.

Although several Congressional aides said Mr. Horowitz's bill of rights had little chance of passing, the American Association of University Professors, a Washington-based nonprofit organization that first codified principles of academic freedom in 1940, has posted a rebuttal to the bill on its Web site, www.aaup.org.

"The danger of such guidelines is that they invite diversity to be measured by political standards that diverge from the academic criteria of the scholarly profession," the statement says. It also argues, for example, that "no department of political theory ought to be obligated to establish `a plurality of methodologies and perspectives' by appointing a professor of Nazi political philosophy, if that philosophy is not deemed a reasonable scholarly option within the discipline of political theory."

At the heart of the dispute is whether the kind of bias cited by Mr. Horowitz — the discrimination against scholars with right-leaning views in hiring and promotion and the stifling of conservative student opinions — is indeed prevalent.

Last year the Center for the Study of Popular Culture surveyed the political opinions of professors in the humanities and social sciences at 32 top universities and concluded that Democratic views vastly outnumbered Republican ones at each of them. To many of Mr. Horowitz's supporters, that is strong evidence.

"We have 60 members in the department of government," said Harvey Mansfield, a well-known Harvard professor. "Maybe three are Republicans. How could that be just by chance? How could that be fair? How could it be that the smartest people are all liberals? Many liberals simply don't care for the kind of work conservatives do."

Many academics interviewed for this article who described themselves as Democrats acknowledged that college faculties were dominated by liberals, partly as a result of leftist activists' entering academia in the 1960's. The question, which has been roiling for nearly two decades now, is whether that has meant a smothering of conservative views.

Stanley Fish, the dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago, fumed at the suggestion that a liberal conspiracy existed among faculty. "I have interviewed 250 job candidates in the last five years," he said. "There is no room at all, in the hiring process, which is heavily scripted, for revealing political and religious orientation." "The question you should ask professors," he said, "is whether your work has influence or relevance."

"A public resolution that is on the record has its own coercive force," added Mr. Fish, whose work on postmodernism as an English professor has long drawn the ire of conservatives. "It can lead faculty members and students to feel that they are under surveillance."

Mary Burgan, the general secretary of the American Association of University Professors, said that universities already had guidelines against any kind of discrimination — including political — and that each year the organization itself looked into 6 to 10 accusations of bias, including ones made by conservatives.

Students for Academic Freedom, a campus organization working closely with Mr. Horowitz, has a Web site, studentsforacademicfreedom.org, where students can report incidents of discrimination.

In 2001 Mr. Horowitz led a campaign to place advertisements in college newspapers denouncing calls for slavery reparations to black Americans. At Brown University, where one of the ads ran, student protesters destroyed copies of The Brown Daily Herald and demanded it pay "reparations" by giving free advertising space to proponents of reparations. (The paper refused but expanded space for opinion articles the day after the incident.)

Mr. Horowitz spoke at Brown in October at the invitation of The Brown Spectator, a conservative magazine founded by Stephen Beale, a senior, and Christopher McAuliffe, a junior, who have asked the student council to pass the academic bill of rights. "We are trying to get the university to say on the record that we embrace intellectual diversity," said Mr. Beale, the son of a theology professor from Massachusetts.

Mr. McAuliffe, a Florida native, said: "I have been assigned Marx four times at Brown. Adam Smith? Not even once."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, April 3, 2004.

*Though not related, please see also: Putting former Haitian murderous dictator Aristide in tight handcuffs, whose job is that?.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |