| Want to send this page to a friend? Click

on the heart at the top of this window. |

| A rickety island becomes yet more unstable |

SEVEN years after American troops intervened to oust a brutal military regime and

reinstate Haiti's democratically elected president, little has changed in Latin America's

poorest country. Although civilians still rule, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide - elected

again last year after a five-year gap - is hardly living up to expectations as the great

democratic hope.

| Serious signs of political instability have also returned.

After almost a decade without a coup, there were two attempts last year,

in July and December. Opposition politicians and journalists have been hounded, and their

offices and homes burned, by the chimère, Mr. Aristide's hired thugs from the slums.

Meanwhile, the economy

has stagnated. Two-thirds of Haiti's 7.8m inhabitants live in poverty, half of all adults

are illiterate, and less than a quarter of rural children attend primary school.

Infant and maternal mortality rates remain among the highest in the world, and Haiti

produces more new cases of HIV*AIDs each year than the entire United States. |

|

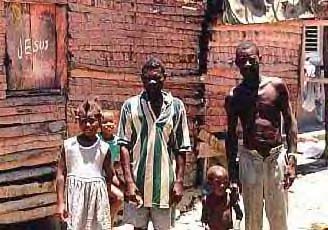

| Well dressed, they pose for the photograph of the

century in front of their hilltop |

|

The government has failed to past a budget in six years. Instead, diplomats suspect,

the country's depleted coffers are being filled with pay-offs from drug-dealers who use

the country to trans-ship an estimated 10-15% of the cocaine that enters the United

States. With notable exceptions - one big tabacco group is investing $40m in a Hilton

franchise by the airport - private industry is struggling to stay afloat. Some of Haiti's

rich families are selling up and moving abroad. They complain of government

corruption and a dramatic rise in kidnappings by armed gangs, some of whom are thought to

have close links to Mr. Aristide's Lavalas Family party.

| The Haitian government blames the rest of the world for

blocking $500m in foreign aid, calling it "economic terrorism". But the

government spent an estimated $7m to buy four official mansions, including a $1.5m hilltop

spread for the prime minister. Within the broad ranks of the Lavalas movement, which first

swept Mr. Aristide to power in 1990 as the champion of the poor, discontent is growing.

For the first time, "Down with Aristide" graffiti have begun to appear. Small

anti-government demonstrations have taken place around the country, and are ruthlessly put

down. On January 27th, the police used tear-gas and live bullets to disperse a crowd of

hundreds who storming a warehouse in Port-au-Prince in protest against corruption in a

rice-importing programme. |

|

A prospective Hilton Hotel |

|

So far, Mr. Aristide has managed to dodge most of the blame. Last week it was the turn

of his prime minister (boyhood friend), Jean-Marie Cherestal, to take the fall after the

chimère demanded his head. "The Mafia wing of the party is trying to take Aristide

hostage," said one member of Lavalas. "It's a bunch of thieves, murderers and

racketeers." The president hangs on largely because of fear of what may follow him.

"Aristide is one of the more moderate in his party," says Richard Coles, a

former president of the Haitian Manufacturing Association. Mr. Coles, one of a small group

of progressive businessmen, worries that the severing of international aid merely plays

into the hands of those in Lavalas "who don't believe in democracy".

Mr. Aristide himself appears to be aware of the threat from within. A few days before

the attempted coup of December, he delivered a dressing-down to top Lavalas officials,

specially warning them against any ties to drugs. Government officials now admit that the

attempted coup may have involved dissident Mafia elements within Lavalas, led by a group

of disgraced former officers in Haiti's now-disbanded armed forces under a former

policeman, Guy Philippe. Mr. Philippe, now under arrest in the Dominican Republic, is one

of nine officers who fled Haiti in November 2000 after foolishly approaching the American

embassy to seek backing for a coup. Several are believed to have drug connections.

The government refuses to take any responsibility for its woes. Instead, it hints at an

international conspiracy to sink Mr. Aristide. Its critics are unimpressed.

The Economist, February 2nd 2002

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of

democracy and human rights |