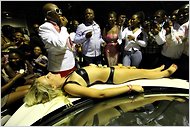

SANDTON, South Africa — Kenny Kunene, a former gangster turned businessman, gave what he called “the mother of all parties” for his 40th birthday. With his small paunch protruding from a white tuxedo and his eyes hidden behind Roberto Cavalli sunglasses, he ate sushi from the belly of a woman who was wearing nothing but black lingerie and high heels while hundreds of guests looked on.

|

By CELIA W. DUGGER |

As the revelers got tipsy on his liquor, he says he treated the most important among them — including Zizi Kodwa, President Jacob Zuma’s stylish spokesman, and Julius Malema, the rabble-rousing leader of the governing party’s youth wing — to $1,300 bottles of Dom Pérignon. Like the American rappers he emulates, Mr. Kunene himself swigged a bottle of Armand de Brignac Champagne that goes for more than $1,500 at his posh nightclub, ZAR, perched on the roof of a five-star hotel.

|

|

GREG MARINOVICH FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| Kenny Kunene, center, a convicted swindler whose business dealings have gained him access to South Africa's elite, has raised eyebrows with his lifestyle. |

His October bash here in Sandton, a Johannesburg suburb often described as the wealthiest square mile in Africa, and another sushi-eating party that Mr. Kunene hosted recently in Cape Town, have turned him into a peculiarly South African sensation. His antics set off raucous bickering in the governing alliance about the conspicuous consumption of a politically networked black elite in a country where the majority of young blacks do not even have jobs.

Zwelinzima Vavi, leader of Cosatu, the powerful trade union federation allied with the governing African National Congress, accused Mr. Kunene of “spitting on the face of the poor” and declared that parties where people who have gotten rich in dubious ways flaunt their wealth “turn my stomach.”

Mr. Kunene, who says he supports the A.N.C.’s Youth League with his time and money, promptly retorted that his was “honest money spent on honest fun.” He describes his success as proof of the nation’s democracy, and he told Mr. Vavi, who is also black: “You remind me of what it felt like to live under apartheid. You are telling me, a black man, what I can and cannot do with my life.”

The Kunene story has crystallized a recurring question about life in post-apartheid South Africa: Is the accumulation and exhibition of such wealth a sign that blacks have finally arrived after an era when whites hogged the high life, or is it evidence of a moral decay undermining Nelson Mandela’s once great liberation movement?

“It raises in such wonderfully stark terms what freedom is and what one does with it,” said Jonny Steinberg, an author and one of the many newspaper columnists who commented on the events. “The idea that one uses it to get rich, and ostentatiously so, and that this is the most important dividend of freedom, is very powerful.”

In recent months, the spectacle of eating sushi from a woman’s body — perhaps familiar to Americans from Samantha’s escapades on “Sex and the City” — has been a source of both lurid fascination and ridicule here. A cartoon by the Mail & Guardian’s Zapiro, titled “The Last Sushi,” depicts a naked woman lying on a long table with well-known businessmen and politicians feasting on the fishy bits that decorate her curves.

That Mr. Kunene, a small-time player in South African politics, has vaulted onto the front pages underscores how salient the issue of economic inequality has become in South Africa, a country that by some estimates has the worst disparities of wealth in the world.

But the focus on Mr. Kunene, nicknamed the Sushi King by headline writers, is also a tribute to his obvious gifts for self-promotion and self-reinvention.

He was raised by his unemployed mother (an evangelical faith healer), his grandfather (a retired English teacher), and his grandmother (a midwife and the family’s only earner) in a black township outside of Odendaalsrus in what is now the Free State. The family could never afford to give him a birthday party, he said, and he always craved luxuries.

When he was a teenager during apartheid, he said he and his friends picked out the houses and cars in wealthy white areas they fantasized would one day be theirs. He dreamed of Porsches. “The objective was to overthrow the government and take everything that the white man had,” he said.

Like his grandfather, he became a high school English teacher. To earn extra money, he opened a small saloon, eavesdropped on gangsters and joined them, hijacking cars, robbing businesses and dreaming up ways to trick people out of their money, he said.

“My heart was not into armed robberies,” he said. “My heart was more into fraud because I’m a thinker.”

But he was caught and convicted in 1997 of helping run a Ponzi scheme. His case alone listed more than 1,900 victims, he said. He served six years in prison. After his release, he went into business with Gayton McKenzie, a bank robber he had befriended behind bars. They sold a book that Mr. McKenzie wrote about quitting a life of crime, and marketed Mr. McKenzie’s motivational speeches to schools and corporate groups.