When Molly Easo Smith delivered her inaugural address as president of Manhattanville College last spring, she opened with an unusual line: “Welcome, namaste, vannakkam, namaskaaram, bienvenidos and welcome.”

By LISA W. FODERARO

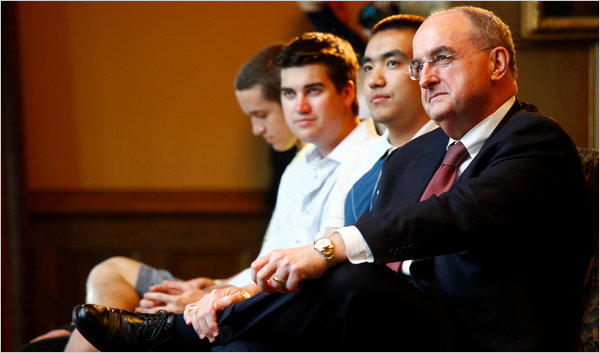

Joyce Dopkeen for The New York Times

Molly Easo Smith, president of Manhattanville College, grew up in India.

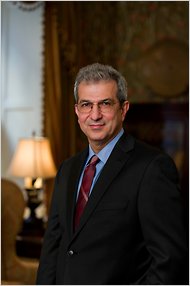

Stevens Institute of Technology

Nariman Farvardin was named president of Stevens Institute of Technology in January.

Three of the greetings were in languages from her native India: Hindi, Tamil and Malayalam. They reflected the striking journey Dr. Smith had made from her birthplace in Chennai — where she had never dated or been outdoors past 6 p.m. when she left at age 23 — to the pinnacle of American higher education: a college presidency.

As colleges in the United States race to expand study-abroad programs and even to create campuses overseas, they are also putting an international stamp on the president’s office. Dr. Smith, 52, has joined an expanding roster of foreign-born college and university leaders.

The Association of American Universities, which represents most of the large research campuses in the United States and Canada, said that 11 of its 61 American member institutions have foreign-born chiefs, up from 6 five years ago. In the past two months, three colleges in the New York region have appointed presidents born abroad: Cooper Union tapped a scholar originally from India; Seton Hall University, a candidate from the Philippines; and Stevens Institute of Technology, a native of Iran.

The globalization of the college presidency, higher-education experts say, is a natural outgrowth of the steady increase of international students and professors on American campuses over the past four decades. And it will most likely lead to more relationships and exchanges abroad, they say, while giving students a stronger sense that they are world citizens — a widely advertised goal in academia.

“There’s a logic to seeing individuals born in other nations, who have excelled in their scholarly work, now move into college presidencies,” said Molly C. Broad, president of the American Council on Education, which represents two- and four-year colleges. “I think the trend will continue and maybe even accelerate as more people move up in the faculty ranks, becoming deans and provosts.”

That trend extends to Washington, where a year ago President Obama named a native of Argentina, Eduardo M. Ochoa, to be his top adviser on higher education, as an assistant secretary in the Department of Education.

The number of international scholars working at colleges and universities in the United States — as researchers, instructors and professors — rose to 115,000 last year, an all-time high, from 86,000 in 2001. That growth, documented by the Institute of International Education, a nonprofit group in New York, came despite the problems in obtaining visas after 9/11.

Allan E. Goodman, the institute’s president, said he had an “epiphany” two years ago about the changing landscape at a banquet in Washington. The gathering honored about 40 scholarship recipients — undergraduates at the nation’s strongest institutions in math and science.

“The first thing I noticed was that nobody looked like me,” said Dr. Goodman, who is white. “At least half, if not two-thirds, were international students. They were from India, Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and yet they were Harvard students, Stanford students, Rice students. It just reminded me that American higher education is not American. It’s for the whole world.”

Still, academic leaders from foreign countries where English is an official language, or is at least widely spoken, may have an edge. Of the 11 foreign-born presidents of institutions that belong to the Association of American Universities, 3 are from Canada (including Shirley M. Tilghman, at Princeton), 1 is from South Africa and 1 is from Australia. The rest hail from China, Greece, France and Cyprus.

While many presidents first arrived in the United States as unproven graduate students, Michael A. McRobbie, president of Indiana University, was recruited 14 years ago from Australia National University to be Indiana’s vice president of information technology, as well as a professor of computer science. He became provost in 2006 and president the following year.

Dr. McRobbie found the Midwestern university to be remarkably diverse, with several thousand international students representing some 100 countries. There are now about 50 students from Australia alone.

He also encountered a warm welcome, feeling every bit a Hoosier. Last fall, on his 60th birthday, Dr. McRobbie took the oath of allegiance as an American citizen, along with his three grown children. “I have been here a long time and have become well accepted in this state,” he said. “They treat me like a local with a funny accent.”

Other journeys to American academia have been more turbulent. Nariman Farvardin, who in January was named president of Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J., recalls struggling to finish college in Iran in the late 1970s, just as the Islamic Revolution broke out.

“The government decided to shut down the university completely,” he said. “I remember there was a tank parked in front of the main entrance of the university. There were daily strikes and demonstrations, and buildings were on fire.”

Then 22 and only a semester shy of graduation, he contacted the American colleges that had accepted him to graduate school. He asked if they would take him instead as a transfer student — immediately. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute said yes, and within weeks, he was en route to Troy, N.Y., from Tehran.

“I was in a state of shock,” Dr. Farvardin, 54, recalled. “I had very little money and no knowledge of the English language.”

He went on to earn a bachelor’s, a master’s and a doctorate from Rensselaer. He then spent the next 27 years at the University of Maryland, where he rose from assistant professor to provost, becoming an American citizen along the way.

“I give an enormous amount of credit to this country,” he said. “There would have been no other place in the world that would have judged me by the value of my contributions and the content of my character. Quite frankly, right now I look at myself as an American, and I think others do as well.”

Although many colleges have tentacles firmly planted abroad, the influx of foreign-born presidents could extend that reach. Dr. Smith, president of Manhattanville College in Purchase, N.Y., where 16 percent of the student body is from outside the United States, said she was interested in exploring an exchange with her alma mater, Madras Christian College, one of India’s leading schools.

“I would love to make that connection,” said Dr. Smith, who became an American citizen in 1989.

Dr. Farvardin, too, wants to ensure that Stevens Institute of Technology is making the most of international study. “We live in an increasingly interconnected world,” he said. “If you haven’t given students the exposure and appropriate experience in how to deal with the global economy, you’ve done them a disservice.”

Copyright 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Education, of Wednesday, March 9, 2011.