CHARLESTON, Mo. — More than a decade ago, a 14-year-old boy killed his stepbrother in a scuffle that escalated from goofing around with a blowgun to an angry threat with a bow and arrow to the fatal thrust of a hunting knife.

|

|

DILIP VISHWANAT FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

|

| Quantel Lotts was 14 when he killed his stepbrother. Now 25, he is serving life without parole. |

The boy, Quantel Lotts, had spent part of the morning playing with Pokémon cards. He was in seventh grade and not yet five feet tall.

Mr. Lotts is 25 now, and he is in the maximum-security prison here, serving a sentence of life without the possibility of parole for murder.

The victim’s mother, Tammy Lotts, said she lost two children on that November day in 1999. One was a son, Michael Barton, who was 17 when he died. The other was a stepson, Mr. Lotts.

“I don’t feel he’s guilty,” she said of Mr. Lotts in the living room of her modest St. Louis apartment, growing emotional. “But if he was, he’s already done his time. He should be released. Time served. If they think that’s too easy, let somebody look over his case.”

As things stand now, though, the law gives Mr. Lotts no hope of ever getting out.

Almost a year ago, the Supreme Court ruled that sentencing juvenile offenders to life without the possibility of parole violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment — but only for crimes that did not involve killings. The decision affected around 130 prisoners convicted of crimes like rape, armed robbery and kidnapping.

Now the inevitable follow-up cases have started to arrive at the Supreme Court. Last month, lawyers for two other prisoners who were 14 when they were involved in murders filed the first petitions urging the justices to extend last’s year’s decision, Graham v. Florida, to all 13- and 14-year-old offenders.

The Supreme Court has been methodically whittling away at severe sentences. It has banned the death penalty for juvenile offenders, the mentally disabled and those convicted of crimes other than murder. The Graham decision for the first time excluded a class of offenders from a punishment other than death.

This progression suggests it should not be long until the justices decide to address the question posed in the petitions. An extension of the Graham decision to all juvenile offenders would affect about 2,500 prisoners.

Mr. Lotts, a stout man with an easy manner, said he was not reconciled to his sentence. “I understand that I deserve some punishment,” he said. “But to be put here for the rest of my life with no chance, I don’t think that’s a fair sentence.”

Much of the logic of the Graham decision and the court’s 2005 decision banning the death penalty for juvenile offenders, Roper v. Simmons, would seem to apply to the new cases.

The majority opinions in both were written by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who said teenagers deserved more lenient treatment than adults because they are immature, impulsive, susceptible to peer pressure and able to change for the better over time. Justice Kennedy added that there was an international consensus against sentencing juveniles to life without parole, which he said had been “rejected the world over.”

One factor cuts in the opposite direction. Justice Kennedy relied on what he called a national consensus against the punishment for crimes that did not involve killings. Juvenile offenders were sentenced to life without parole for such nonhomicide crimes, he wrote, in only 12 states and even then rarely.

There does not appear to be such a consensus against life without parole sentences for juveniles who take a life. That may be why opponents of the punishment are focusing for now on killings committed by very young offenders like Mr. Lotts.

That strategy follows the one used in attacking the juvenile death penalty, which the Supreme Court eliminated in two stages, banning it for those under 16 in 1988 and those under 18 in 2005.

Kent S. Scheidegger, the legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, a victims’ rights group, said that categorical approaches were misguided in general and particularly unjustified where murders by young offenders were involved.

“Since I think Graham is wrong,” he said, “extending it to homicides would be wrong squared.”

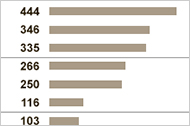

“Sharp cutoffs by age, where a person’s legal status changes suddenly on some birthday, are only a crude approximation of correct policy,” he added. There are around 70 prisoners serving sentences of life without parole for homicides committed when they were 14 or younger, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law firm in Alabama that represents poor people and prisoners.

The effort to extend the Graham decision has so far been unsuccessful in the lower courts. According to a study to be published in The New York University Review of Law and Social Change by Scott Hechinger, a fellow at the Partnership for Children’s Rights, 10 courts have decided not to apply Graham to cases involving killings committed by the defendants, and seven others have said the same thing where the defendants were accomplices to murders. Courts have reached differing results, though, where the offense was attempted murder.

All of this suggests that the question left open in Graham may only be answered by the Supreme Court. In March, lawyers with the Equal Justice Initiative asked the justices to hear the two cases raising the question.

One concerns Kuntrell Jackson, an Arkansas man who was 14 when he and two older youths tried to rob a video store in 1999. One of the other youths shot and killed a store clerk.

The second case involves Evan Miller, an Alabama prisoner who was 14 in 2003 when he and an older youth beat a 52-year-old neighbor and set fire to his home after the three had spent the evening smoking pot and playing drinking games. The neighbor died of smoke inhalation.

In Mr. Lotts’s case, too, state and federal courts in Missouri have said that his sentence is constitutional. In December, in a different case, the Missouri Supreme Court divided 4-to-3 over the constitutionality of the punishment in a case involving the killing of a St. Louis police officer.

A dissenting judge, Michael A. Wolff, wrote that “juveniles should not be sentenced to die in prison any more than they should be sent to prison to be executed.”

At the prison here, about 130 miles south of St. Louis, Mr. Lotts said he had grown up around drugs and violence, and he acknowledged that he used to have a combustible temper. But he said the years he spent living with his father and Ms. Lotts were good ones.

He and his brother Dorell were inseparable, he recalled, from Ms. Lotts’s three boys. The group was sometimes taunted because Quantel and Dorell were black and the other boys were white.

“If you wanted to fight one of us,” he said, “you had to fight all of us.”

He said he recalled very little about assaulting Michael. But he said he knew some things for sure.

“That’s my brother,” he said. “Why would I want to kill my brother? That’s not what I set out to do. That’s not what I meant to do. That’s not what I intended to do.”

Tammy Lotts said race figured in her stepson’s trial. “They said a black boy stabbed a white boy,” she said. For years, state officials prohibited her from visiting Mr. Lotts, fearing she would try to harm him. “I’m the victim’s mother,” she said, shrugging.

At the prison last week, Mr. Lotts was wearing a handsome wedding ring, and it prompted questions. Beaming, he said he had been married just a few weeks before to a woman who had written to him after hearing him interviewed. He pointed to where the ceremony had taken place, a couple of yards away, near the vending machines.

Ms. Lotts attended the wedding, but only after satisfying herself that the bride was a suitable match.

“She’s marrying my son,” Ms. Lotts explained.