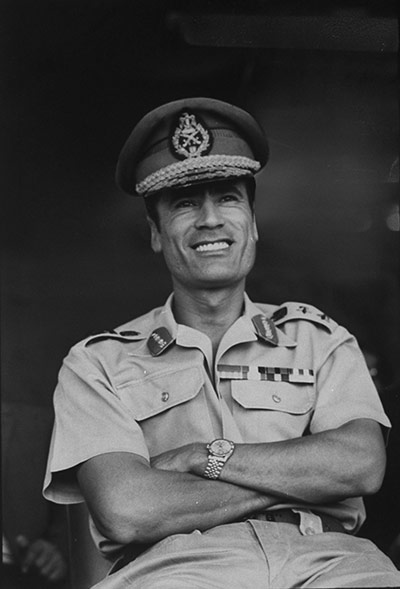

FORTY-TWO years after he took power in a coup as a handsome 27-year-old captain, Africa’s longest-serving dictator was finally brought to bay on October 20th in his home town of Sirte. At first it was said that Muammar Qaddafi had been wounded. Later reports, as The Economist went to press, suggested he had died.

Either way, his demise spells the end of a vile reign. He tormented his own people and made mischief far and wide—in his own country, across Africa and the Arab world, and in the skies and cities of Europe. Some, among his own tribesmen and in parts of sub-Saharan Africa that received his largesse, may mourn his demise. But for the overwhelming mass of humanity, at home and abroad, his capture is a cause of undiluted celebration.

The fall of Sirte, which followed that of the other surviving holdout town of Bani Walid, means that virtually the whole of Libya is in the hands of the forces that took up arms against the colonel in February. The country is not entirely safe, however. In Abu Salim, a suburb of Tripoli where support for the colonel was deemed strongest, there was a recent armed eruption of opposition to the new rulers, albeit quickly put down. In the vast desert to the south of the coastal strip where more than 90% of Libyans reside, there may be pockets of resistance. It could take time for pro-Qaddafi people to be fully defeated and rounded up. The whereabouts of the colonel’s most prominent son, Seif, are not yet known.

The fall of the colonel marks only the beginning of a hoped-for political, economic and moral renaissance. Justice will need to be done, and be seen to be done; but reconciliation must also be pursued. It is up to the new ruling authorities, led by the avuncular chairman of the transitional national council, Mustafa Abdul Jalil, to balance the two.

The fledgling government’s behaviour in Tripoli and elsewhere suggests that it will go out of its way to avoid undue triumphalism. Leaders of the transitional council have said that all of the body’s members will step down within a month of the total liberation of the country and that a new government, also transitional, will be set up leading to elections within a fairly short time; some say less than a year, others perhaps two years.

Meanwhile, the economy has shown early signs of bouncing back, as the country’s plentiful oil wells begin pumping again. Production has already exceeded 350,000 barrels a day (b/d) and is set to rise to 1m b/d within four months or so. Libya’s 6m-plus people should, if a more efficient and decent system of government is established, become some of the most prosperous in the world.

But politics is another matter. There is already rivalry between Islamists and secular-minded people, between tribesmen and urbanites, between east and west, between Tripoli and Benghazi, the original rebel headquarters in the east. Some Western observers already fear the Islamists have the upper hand—and may not remain pro-Western for long. But so far Mr Abdul Jalil and his de facto prime minister, Mahmoud Jibril, seem level-headed and sincere in their insistence that they want to help build a pluralistic and democratic state.

Fallen at last

The colonel’s final fall is also welcome news for David Cameron, Nicolas Sarkozy and for NATO. Heavily criticised for willing an end without having the means to achieve it, both the British prime minister and the French president stuck to their guns even when some of the military advice they were receiving was glumly predicting a long-drawn-out stalemate and the division of the country into a pro-Qaddafi west and an anti-Qaddafi east.

NATO too came under fire, particularly in America, for its at times cautious approach to targeting and for lacking the firepower without greater American participation to bring about a decisive conclusion. In fact, the extreme accuracy of the thousands of missions flown by NATO aircraft (mainly British and French) patiently ground down the regime and reduced its ability to carry on fighting. Moreover, it did so with remarkably few civilian casualties.

More importantly for the Arab world in general, it will provide a fillip for those who seek to build democracy and the rule of law elsewhere. Tunisia is due on October 23rd to hold an election to a constituent assembly. Egypt, though passing through a rocky patch, is still on course to hold an election next month that should lead to the removal of the military authorities and the establishment of a proper democracy. So, with luck, a belt of countries across north Africa should now see democracies gradually entrenched. The demise of Colonel Qaddafi is a vital piece of the jigsaw falling into place.

Use the interactive "carousel" to browse our coverage of the Arab uprising through graphics

Use the interactive "carousel" to browse our coverage of the Arab uprising through graphics

The rest of the Arab world still has a long way to go. Syria remains turbulent. Week after week, protesters are continuing courageously to demonstrate against the regime of President Bashar Assad, perhaps the nastiest in the region after Colonel Qaddafi’s. The forces of democracy there too will be given a big boost.

The end of Colonel Qaddafi may be a largely symbolic moment. It will not necessarily spell the onset of sweetness and light across the region. But it is a turning point all the same.

AFTER days of shelling during which untold numbers of diehard loyalists and unfortunate civilians were traumatised, maimed and killed, the despised dictator was cornered like an exhausted fox at the end of the hunt. How he took the bullet that killed him was disputed—in crossfire, the confusion of battle, or in what amounted to an execution. But so what? It was kinder than the lingering, agonising death he deserved and he was better dead than alive. Whoever pulled the trigger should be counted a hero, not investigated as a war-criminal. This was a time for rejoicing: a war over at last, and one of the great villains of the past half-century rendered incapable of causing further cruelty.

AFTER days of shelling during which untold numbers of diehard loyalists and unfortunate civilians were traumatised, maimed and killed, the despised dictator was cornered like an exhausted fox at the end of the hunt. How he took the bullet that killed him was disputed—in crossfire, the confusion of battle, or in what amounted to an execution. But so what? It was kinder than the lingering, agonising death he deserved and he was better dead than alive. Whoever pulled the trigger should be counted a hero, not investigated as a war-criminal. This was a time for rejoicing: a war over at last, and one of the great villains of the past half-century rendered incapable of causing further cruelty.