| |

|

|

TODD HEISLER/THE NEW YORK TIMES

|

| A mural in the Bronx memorializing Amadou Diallo, the Guinean immigrant who was shot by police officers in 1999. |

But by the time she began her job as a housekeeper at the Sofitel in 2008, she had legal status and working papers, her lawyers said.

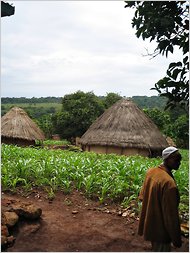

After coming to the United States, she settled in the Bronx, where many in New York City’s small Guinean population have blended in among other West African immigrant groups in neighborhoods like High Bridge, north of Yankee Stadium, Claremont and Morrisania.

The community was still recovering from the killing of Amadou Diallo, a street vendor from the woman’s region and ethnic group, who was shot to death by the police in 1999 in a case that received widespread attention. The officers were acquitted after testifying that they had mistakenly thought he was pulling out a weapon.

The woman melted into this community. She did not seem to be well known even in the neighborhoods where Guineans often lived.

After prayers at a few West African mosques, Guineans often go to Guinean-owned restaurants to eat cooked cassava leaf and beef stew, drink homemade juice made from hibiscus flowers and watch television broadcasts of African news and sports. They shop at Guinean stores that sell West African staples like cornmeal, yams, palm oil and spices.

In Guinea, a former French colony, many people closely follow the news from France. In fact, one of the oddities of this case is that before he was arrested, Mr. Strauss-Kahn — often referred to in the Francophone world as DSK — was probably better known in Guinea, at least among the educated, than in the United States. (It does not appear that the woman knew of Mr. Strauss-Kahn before the encounter in the hotel room.)

After arriving from Guinea, the woman showed up one day at African American Restaurant Marayway, near Grand Concourse in the Bronx, looking for a job, recalled the owner, Bahoreh Jabbie, who hired her.

For several years, she worked the busy evening shift, helping Mr. Jabbie and his wife, Fatima, in the kitchen behind smudged bulletproof glass or serving customers at the restaurant’s three tables. Her daughter sometimes stopped by to visit.

Mr. Jabbie, an immigrant from Gambia, in West Africa, said the woman revealed little about her private life, but was a steady worker. “She was good with me,” he recalled.

During this period, she received asylum, her lawyers have said, though they have not revealed the basis of her asylum petition to federal immigration authorities.

According to community leaders and immigration lawyers, most Guineans who have received asylum in recent years have sought sanctuary from political persecution in their homeland, though others have petitioned to avoid social practices, like female genital cutting and forced marriage.

One day, the woman told Mr. Jabbie that she was leaving the restaurant for a better paycheck at the Sofitel hotel.

With that, she entered a new world, with a grand, golden canopy and wood-paneled suites, blocks from Times Square. She was considered a good employee there.

In her telephone calls home to Guinea, her brothers recalled, she talked only about her daughter, now in her teens, and never about the rest of her life.

Still, she could have drawn on the company of a growing extended family, with one relative living among a cluster of West Africans on Wheeler Avenue in the Bronx, where a street sign and mural commemorate Mr. Diallo near the building where he was shot.

“On Sundays, he had 50 to 60 people over in the backyard,” recalled Andre Landers, a retired police officer and neighbor, referring to the woman’s relative. “When they had a baby born, they had ceremonial get-togethers.”

The only other hint of the woman’s social life came from acquaintances who said she would sometimes stop by a West African restaurant, Café 2115, on Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Harlem, where livery-cab drivers and others eat, socialize and watch French news programs on widescreen televisions.

“She isn’t a fiery woman,” said a friend, who did not want to be identified so as not to appear to be meddling in the case.

At home, for fun, the woman watched Nigerian comedies on DVD, the friend said. “She was watching that every day,” he added.

Newfound Scrutiny

For now, her life, once unremarkable, is under intense scrutiny — by journalists and lawyers, and investigators working for the prosecution or the defense. Mr. Strauss-Kahn’s lawyers have already suggested that any sexual encounter was consensual, an assertion that her lawyer has called preposterous.

Her lawyer is a former federal prosecutor whose practice includes criminal defense and employment discrimination matters, and who has obtained large civil settlements for his clients.

Meanwhile, in the immigrant neighborhoods that she has called home for the past nine years, residents are also trying to get a sense of a woman very few have met.

For many in the Guinean population, which has fierce ethnic rivalries that reflect tensions back home, the case has taken on a special resonance.

The woman is a member of the Fulani ethnic group, Guinea’s largest, which has suffered years of persecution by other ethnic groups. Many Fulani feel that their grievances have never been fully addressed.

“It wakes up the trauma that we have,” said Mamadou Maladho Diallo, a Fulani journalist in New York.

The woman’s brothers in Guinea said they had not spoken with her since the hotel encounter with Mr. Strauss-Kahn. One brother produced a notebook with several New York cellphone numbers that he said were his sister’s. He has tried calling them, but no one has answered.

The brothers seemed worried and confused about what was happening.

But they said their sister’s upbringing would anchor her as the case against Mr. Strauss-Kahn proceeded.

“She has faith,” her brother Mamadou said. “She will never change that.”

Adam Nossiter reported from Guinea, and Anne Barnard and Kirk Semple from New York. Reporting was contributed by John Eligon, William K. Rashbaum and Rebecca White from New York, and Abdourahmane Diallo from Guinea.