It sounds like the plot of a movie: “Catch Me if You Can,” the 2002 high-spirited Steven Spielberg thriller about a serial impostor named Frank Abagnale Jr., who managed to pass himself off as an airline pilot, a doctor and a lawyer, while making millions of dollars forging checks. Or maybe something darker, like Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 classic, “Shadow of a Doubt,” about a man wanted for murder who hides out with his sister’s family in a quiet California community where he charms the unsuspecting townsfolk.

|

| Mark Schafer |

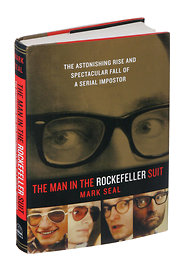

In the real-life story recounted in the journalist Mark Seal’s fascinating but weirdly incomplete new book, “The Man in the Rockefeller Suit,” one Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter arrives in America from Germany at 17 and over the years assumes a succession of identities, eventually passing himself off as Clark Rockefeller, “reluctant scion of the family with the country’s most famous name.” He finagles jobs with a succession of Wall Street firms; marries a woman named Sandra Boss, who quickly ascends the corporate ladder at the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company; and insinuates himself into the privileged world of prep-school-and-Ivy-League-educated, upper-crust New York and Boston.

Mr. Seal, who interviewed almost 200 people for this book, fashions a brisk narrative that has all the pace and drive of a suspense novel. He also adroitly orchestrates two dovetailing plotlines that lead to the investigation and exposure and arrest of this con man: one involving Mr. Gerhartsreiter’s pre-Rockefeller days in California, where he was linked to the strange disappearance of a married couple (one of whom turns up dead); the second dealing with his kidnapping of Reigh, nicknamed Snooks, his 7-year-old daughter with Ms. Boss.

One of the problems with this book is that it never sheds much light on the psychological reasons behind Mr. Gerhartsreiter’s need to create fictional personas for himself. Mr. Seal does little more than observe the obvious: that the young man wanted to escape the suffocating little town in Germany where he grew up. And aside from noting that Mr. Gerhartsreiter might have picked up some tips from the film noir movies he loved to watch, Mr. Seal also fails to illuminate the means by which he managed to pull off his elaborate scams.

How did he acquire a collection of fake paintings — including copies of works by Rothko, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell and Mondrian — good enough to fool an art dealer and a painter? How did he fool his wife for more than a dozen years, using her money to buy a New Hampshire estate and 23 cars? How did he get away with dispensing outrageous promises — like a vow to buy his daughter’s school a planetarium — when he almost never picked up a dinner check and his wife didn’t even know whether he had a bank account?

We are repeatedly told that the so-called Clark was charming and that women found him attractive — something clearly not demonstrated by the photographs in this volume — and that his lies were so big, so preposterous, that few people thought to question them. Still, the reader has a hard time understanding how he could hoodwink so many people for so many years. His conversational style — which he seems to have learned by studying Thurston Howell III, the millionaire character on “Gilligan’s Island” — is by most accounts absurdly studded with the snooty anachronisms found in old “tennis anyone?” movies ( “Oh, isn’t this grand!”). And his taste in clothes — silk ascots, bow ties and trousers embroidered with ducks — sounds more like a parody of preppie wear than the real thing.

What Mr. Gerhartsreiter clearly possesses is a pathological liar’s novelistic imagination. He concocted entire back stories for the characters he invented — before Clark Rockefeller, there was Christopher Chichester XIII, a relative of Sir Francis Chichester, the adventurer who had sailed around the world, and Christopher Crowe, a Hollywood producer who claimed to be related to Lord Mountbatten. And he embroidered his creations with a filigree of eccentric detail that may or may not have been drawn from his own life. Chip Smith, for instance, another invented personality, ate only white food; Clark never wore socks and reportedly outfitted his New York apartment with lawn furniture.

Clark also claims to have grown up on Sutton Place, attended Yale at an absurdly young age and owned a J-boat, a classic sailing yacht that belonged to his grandparents. He tells one friend that this yacht was named True Love, and that his family, in Mr. Seal’s words, was “miffed that the producers of the 1940 film ‘The Philadelphia Story,’ starring Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn, had lifted the name to use for the yacht in the film.”

He adds that he recently sold the boat to the singer Mariah Carey and Tommy Mottola, then her husband, disdainfully laughing at the idea of their using it as a pleasure boat because “a J-boat is a racing boat and not a proper place to host parties.”

One Clark friend defends him to Mr. Seal, arguing that “in some ways one has to see Clark as an archetypal immigrant, who constructs a new life and a new persona, free of the constraints of the country he left behind.” All Americans, he adds, “are our own inventions. That’s part of the allure of this country.”

But as described by Mr. Seal in these pages, Clark Rockefeller is no Jay Gatsby — no romantic believer in the American Dream, no innocent in pursuit of a lost love or some platonic conception of himself. Nor is he a Frank Abagnale Jr. in “Catch Me if You Can,” pulling off youthful pranks in the hopes of somehow recapturing the familial security his larcenous father had lost.

No, Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter a k a Christopher Chichester a k a Chip Smith a k a Clark Rockefeller is a pure and simple con man, who lied to his family and friends, who repeatedly used and discarded people and carelessly moved on, always in search of another mark, another credulous individual he could dupe with his extravagant fictions.