| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted Monday, April 5, 2004 |

The Saturday Profile |

First Grader, Model Student, Great-Grandfather |

By MARC LACEY |

|

|

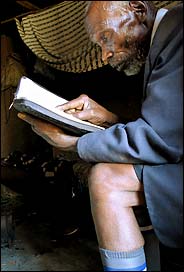

| Guillaume Bonn/Think, for The New York Times | |

'Let them who want to make fun of me do it. I will continue to learn.' |

KIMANI NGANGA MARUGE |

KAPKENDUIYWA, Kenya — Kimani Nganga Maruge is living proof that an old man, even one who leans heavily on a cane and cannot see or hear too well, can learn new tricks.

By his own reckoning, Mr. Maruge is 84. He has no papers to prove his age, but his late father, an illiterate laborer, used to carve a notch in a stick every time a new child was born into the family. Mr. Maruge's notch, one of many his father would carve over the course of his life, indicates that Mr. Maruge came into the world sometime around 1920.

Mr. Maruge is a widower who himself fathered 15 children, 5 of whom survived. He is a great-grandfather who never spent a day in school. His own father had insisted that he look after the family's herd of livestock.

But all that changed when the Kenyan government declared a year ago that primary school education would be free through grade 8. Millions of new pupils showed up at neighborhood campuses, swelling enrollment from 5.9 million students to 7.3 million virtually overnight. Mr. Maruge, with his gray beard and weathered face, was among those in line.

On the first day of school, he put on some gray knee socks and blue trousers that he had cut off above the knee to resemble the short pants worn by schoolchildren all over the country. With his school uniform in place, he limped his way from his mud hut to the office of the headmistress, Jane Obinchu.

She thought Mr. Maruge was joking when he said he was there to enroll in the first grade. But Mr. Maruge was insistent, and Mrs. Obinchu decided to give him a chance - a spot right up front where he could hear her.

The other students, most of them 78 years younger than Mr. Maruge, were amused at first by the old man's presence. But over time they grew used to having a "Mzee," the Swahili honorific given to elders, as a classmate.

After all, Mr. Maruge practiced writing the A B C's just as they did. He worked on basic math problems right alongside them. Slowly, the entire class, Mr. Maruge included, began to learn to read.

Kenyan officials were stunned that Mr. Maruge and others well beyond school age had sought to take advantage of free primary education. "We never knew that such people would come," said S. K. Karaba, senior deputy director in the Department of Education. "They still want to be taught. There is an urge."

Overwhelmed by the onslaught of new students, school administrators did what they could. They crammed the newcomers into already overstuffed classrooms. Sometimes, they took out all the desks to accommodate more youngsters. In extreme cases, students were taken outside into the schoolyard, where they learned under trees.

At Kapkenduiywa Primary School, which Mr. Maruge attends, the enrollment more than doubled to 865 students. Including Mr. Maruge, 109 of them were in Jane Mathenge's first-grade class.

Eventually Kenyan education officials ruled that it was not proper to have adults in the same classrooms as children. Mr. Maruge and the others, including a 64-year-old woman who had also joined the first grade, were told to enroll in adult education classes.

But Mr. Maruge would have none of that. He explained that he would feel intimidated in such an environment. He said that because he had missed out on schooling as a boy, he felt compelled to start at the beginning. That meant the first grade.

School officials found a compromise. They moved Mr. Maruge into an adjacent classroom, which he shares with four special-education students who receive individualized instruction.

Now, Moses Chemworem is Mr. Maruge's teacher, and he has worked out a curriculum that keeps the oldest student in the school engaged. "He's very determined," Mr. Chemworem said.

There were those in his village who thought Mr. Maruge had gone mad when he began going off to school every morning dressed like a youngster. But he had his defenders as well. "He's not a madman," said Chacha Abdala Juma, 74, a village elder and friend who himself finished second grade. "I know him. He's not senile."

Mr. Maruge, not the least bit embarrassed to be in the same school with two of his grandchildren, dismisses his critics with a wave of his cane. "Let them who want to make fun of me do it," he said. "I will continue to learn."

He is learning to read, which he says will help him determine whether the preacher at his church is actually following the Bible. And he is learning basic math. When he gets confused, he uses rocks to help him calculate the numbers. Mr. Maruge says mastering math will allow him to better keep track of his money.

HE has little money to count right now, but he expects that to change, too. He is a veteran of the Mau Mau movement, which fought against the British for Kenya's independence in the 1950's and 60's. He says he was tortured by British soldiers during that time and has joined other former Mau Mau fighters in seeking compensation from the British government.

Whether the claim will succeed, nobody knows for sure. But Mr. Maruge is honing his addition and subtraction skills just in case the windfall arrives.

If his writing improves enough, he says, he may just write a history of the Mau Mau movement. He says he would write about how he used to work for a white settler, a man he called Bwana Jim. He acted as though he was a loyal servant to Bwana Jim, he says, but he was really spying on him for the Mau Mau.

At Kapkenduiywa Primary, Mr. Maruge is now a fixture. He is frequently the first student to arrive in the morning, sometimes an hour early. During the school day, he plays the role of both student and teacher. He feels free to give advice to his classmates, reminding them frequently to study hard and listen to their parents. And he also regales the teachers, most of whom are half his age, with stories about Kenya's earlier days.

"We learn a lot from him," said Mr. Chemworem, his teacher. "He's like a history book."

When the school day is over, Mr. Maruge walks back to the home he shares with his sister. He tends his small herd of sheep and his goats and chickens. Later, he pulls out his books to study a bit before dinner. He is the only student at the school who asks his teacher for homework.

"We thought he might come for a week or so and then give up," said Mrs. Obinchu, the school administrator. "He hasn't given up."

She praised him for following the school rules to the letter. "He never comes to school late," she said. "He never disobeys. He wears his uniform."

Mr. Maruge is an inspiration to his younger classmates when it comes to study habits, as well. "Be like the old man," Mrs. Mathenge told her class of 6-year-olds the other day. "Some of you come here to sleep. See how he reads his books? You ought to learn like him."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Saturday, April 3, 2004.

*Related text: A man who has passed many tests vies with one more

*Please see also, though not related: Putting former Haitian murderous dictator Aristide in tight handcuffs, whose job is that?

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |