Bernard’s first wife died at the age of 30 of a rare blood disease; Scott was about 4 years old. Bernard eventually moved back to Syracuse and with the help of friends and relatives, raised his three young children. He remarried and had a child with his third wife. As the years went by, he and his son grew close.

Father and Son, Bunking in G Block

|

|

FRED R. CONRARD/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| FAMILY TIES Bernard Peters and his son, Scott, above, at Elmira Correctional Facility, where the have shared a cell for nearly all of the last 15 years. |

By MANNY FERNANDEZ

SCOTT PETERS and his father, Bernard, eat dinner together at night, then watch bowling or classic boxing matches on television together into the evening. They have an extremely close relationship: They have seen each other for at least part of nearly every one of the last 5,455 days. Every night, they sleep together in an 8-by-12-foot room, where the alarm bell rings in the morning but also at 10:30 p.m., when the guards turn off the lights in G Block, at the Elmira Correctional Facility.

|

|

HEATHER AINSWORTH FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

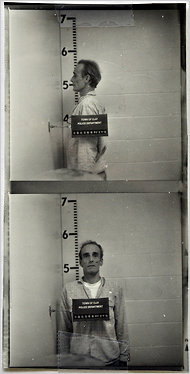

| Bernard Peterses' mug shot, taken after his arrest in connection with a shooting and a string of robberies in 1995. |

It might be the premise for some kind of Hollywood buddy movie, or the latest twist for a reality television series: A father and son who did the crime together, and are now doing the time together. Scott, 42, and Bernard Peters, 69, are inmates 96B1091 and 96B1092 at Elmira, a maximum-security prison in upstate New York. For all but a few months of their nearly 15 years there, they have been cellmates.

Bernard Peters sleeps on the bottom bunk, on account of his bad back, and his only son sleeps on the top. Behind a heavy steel door with a small set of bars in the center, they work on their appeals, write letters and watch the Super Bowl. Years ago they lived on a four-acre farm outside Syracuse, in rural Madison County. Now they occupy a room — G Block, 2 Company, 2 Cell — in the state’s fourth-largest maximum-security prison, where they can see a piece of the sky from the windows on the back wall.

Nearly 200 of the roughly 1,800 inmates at Elmira share a cell with someone — prisoners call it “double bunking.” And while many of those nearly 200 might have shared friends, interests or hometowns, only the Peterses are related by blood.

Although there are few relatives sharing cells, intergenerational incarceration — family members who have ever been imprisoned, in the same or different facilities — is not uncommon around the country. Of the estimated 600,000 parents of minor children in the nation’s state prisons in 2004, half had a relative who was currently or used to be incarcerated, according to a federal Bureau of Justice Statistics report.

Officials with the state Department of Correctional Services said the Peterses’ experience of prison is most likely a rare one. They said they did not know how many parent-child pairs were sharing cells in the prison system, which includes 57,000 offenders at 67 facilities, because they do not track such data, but it is unusual for a father and a son to be in the same prison at the same time. Additionally, only 3,000 of the more than 20,000 maximum-security cells statewide are double-bunk cells of various kinds, making the Peterses’ situation that much more unusual.

The Peterses recognize that their housing arrangement is uncommon, and they said they considered it not a perk but a privilege. “For me, it’s a blessing because I get to keep my eye on him, now that he’s a little older,” Scott Peters said of his father, during a recent interview in a conference room next to the prison visiting area. Burly, tattooed and bearded, Scott can look tough without even trying, but his years in prison seem to have softened him. “It gives me a peace of mind. I know where he is. I know how his health is doing. If we were separated, I would have to stress out about that, not knowing.”

S. J. Wenderlich, deputy superintendent for security services at Elmira, said that the Peterses had been ideal double-bunk inmates. “I think it’s rare that we have a father and son in prison together, but I don’t think it’s so odd that the department would let them double bunk,” Mr. Wenderlich said. “My job is to keep a lid on the place. If I can find two people that get along well and double bunk, usually that means that I’m going to keep two more people out of trouble.”

FOR much of his life, staying out of trouble was not much of a problem for Bernard Peters. He grew up in and around Syracuse and, after serving as a medic in the Navy in the late 1950s and early 1960s, ran a youth community center in Far Rockaway, Queens. He and his first wife, Sandra, were living in Far Rockaway in 1968 when Scott, the third of their three children and only son, was born. Bernard was a milkman for Dellwood Dairy at the time. “I was what you would call a goody-two-shoes,” he said. “I came from a good home. They raised me good. My father never had a speeding ticket in his life.”

|

|

FRED R. CONRARD/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| An undated Peters family snapshot of a visit at the prison. |

“Too close,” Scott Peters said. “We used to fight all the time. We sort of came to a mutual understanding where, it was like, why are we doing this? He always kept us in a nice area. We never lived in a bad area. My mother passed away when I was very young. I really don’t remember her. It probably would have been easier to split us up, but he kept us together.”

Scott Peters’s life was more troubled than his father’s. He dropped out of high school — “I wasn’t getting nowhere at that time in my life. I wasn’t stupid. I was just never going,” he said — and lied about his age so he could start working in restaurants. Later, he worked construction. Scott lived with his father until he was in his late teens, when he moved to an apartment in the Syracuse suburb of Liverpool with his wife — they married in 1987, when he was just 18 — and their first child.

Scott was 19 when he was arrested and jailed in nearby Clay, after he threatened neighbors with a 12-gauge shotgun and a knife because they refused to quiet down a loud party. In 1989, he provoked a seven-hour stand-off with the Onondaga County Sheriff’s Office that ended with the SWAT team lobbing tear gas into the basement where he had been hiding. Deputies had come to the house where he was staying to arrest him on misdemeanor assault and criminal mischief charges after a fight with his wife, Adrienne. “He keeps telling me he’s going to kill me, and I tell him if he does I’m coming back to haunt him,” she told The Post-Standard of Syracuse at the time.

After the stand-off, a judge issued court orders requiring him to stay away from her for six months and to undergo a psychiatric exam.

By the early 1990s, Bernard Peters was living in Liverpool with his third wife and working at a bowling alley. It was around this time that his life began to unravel. Scott Peters had moved back home to be closer to his father. In the summer of 1995, they were accused of embarking on a brief but violent string of robberies in Clay that netted them $2,900 in cash.

Among their victims was Mary Halloran, 61, the manager of the Salvation Army thrift shop in town. The father and son were charged with shooting and robbing Mrs. Halloran in the parking lot of the store as she carried a bag filled with $726 to her car on Aug. 26, 1995. The money was the day’s proceeds from the sale of goods that had been donated to support the Salvation Army’s drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs in Syracuse. Mrs. Halloran was shot once in her right thigh.

When investigators from three law enforcement agencies raided the Peterses’ house after the Salvation Army robbery, they found a stockpile of rifles, pistols, knives, nunchucks, ammunition and a police baton.

The Peterses pleaded not guilty to the charges, and though both men expressed remorse for the crimes in interviews, they spoke in generalities about the robberies rather than in specifics. Bernard said he did not remember who came up with the idea to rob the Salvation Army. Asked whose idea it was, Scott would say only that, “We were just out there together.” And although Bernard appears to be the one who shot Mrs. Halloran, according to court documents, Scott said he did not blame his father for his life behind bars.

“I blame myself,” he said. “I knew right from wrong. I knew better. I was just so mad at the world I didn’t care. I was trying to work and do the right thing with my children and I wasn’t getting nowhere. So I just started doing the wrong things. Picking a gun up and going out and getting money, which I knew was wrong then.”

The jury deliberated about seven hours before finding them guilty of second-degree attempted murder, robbery and other charges.

Sitting near the Elmira visiting room, Bernard Peters said he could not explain how and why he and his son ended up at the Salvation Army that day. “Bad choices, bad decisions,” he said. “There is no one answer for it. There isn’t. If there was, then I would feel a lot better why I am here.”

|

|

CARL J. SINGLE/THE POST STANDARD |

| FALLOUT The authorities with weapons seized at the Peterses' home in 1995. |

|

|

FRED R. CONRARD/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| John Halloran with a 1952 portrait of his wife, Mary, who was shot when the Peterses robbed her. She died in 1999. |

On the day of the Peterses’ sentencing, May 7, 1996, Judge Patrick J. Cunningham seemed equally puzzled, and suggested that drugs had played a role. “I looked through this pre-sentence report,” the judge said from the bench. “I’m looking for something to tell me why you would do a totally evil, senseless thing like this, and I can’t find anything. It says Crazy Bernie is your nickname. Maybe that has something to do with it. But all of a sudden you’re crazy. I suspect cocaine. I suspect you were into the drug cocaine and lost whatever control you had.”

Mary Halloran was in the courtroom that day, and she spoke of the toll the shooting had taken on her. “My golden years are anything but,” she told the judge. “Instead of travel, my days are spent in therapy and going to the doctors, with the possibility of more surgery. I am a prisoner with no chance of parole.”

She asked the judge to impose the maximum sentence, and he did. Scott Peters, who was turning 28 the next day, was given a sentence of 25 to 50 years. His father, then 54, received a longer sentence, but because of a state sentencing reduction statute is now also serving 25 to 50 years. Judge Cunningham allowed Scott and Bernard Peters to gather for a moment with their relatives in a corner of the courtroom. The two men embraced, and cried.

They said the judge had told them they might never see each other again.

THAT’S not how it turned out. Chained together, they rode in a van to Elmira, where they were placed in separate cells in late May 1996.

A few weeks later, Bernard Peters said he wrote a letter by hand to Floyd G. Bennett, the prison superintendent at the time, asking if he and his son could share a cell. At Elmira, as at the state’s other maximum-security prisons, inmates can be placed in shared cells on either a mandatory or voluntary basis. If there is a shortage of single cells, prison administrators can require inmates to share double-bunk cells temporarily, for a period of 60 days. But in most cases, inmates request to share a cell with one another, subject to prison officials’ approval. Those with a history of assaultive behavior or sex crimes are not considered good candidates.

In the Peterses’ case, the request was granted and, except for a few brief periods, including when Scott was transferred for several weeks in late 2000 to a disciplinary housing unit known as long-term keep-lock for threatening a guard, they have shared a cell, though different ones over the years.

In their G Block cell, where they have been since 2007, the sections of the walls where they are allowed to put up photos are decorated with snapshots of Scott’s three children and five grandchildren — Bernard’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Scott and Bernard Peters said the shared cell has made their prison sentences somewhat easier to bear, both for themselves and for their relatives. Instead of spending hours on the road driving to two prisons to visit them, their family members travel to one place.

Their housing arrangement shocked John Halloran, whose wife died of cancer four years after the shooting, at 66. Mrs. Halloran, who had come to America from Ireland in the 1950s as a teenager, had been the mother of four and grandmother of 12. She was shot a few days before their 36th wedding anniversary. In an interview, Mr. Halloran said he blamed the shooting for her cancer: he believed it affected her immune system. He said prison officials should have prohibited the Peterses from sharing a cell.

“It’s totally wrong,” said Mr. Halloran, 74. “I go without my wife. Let him go without his son, or the son go without his father. I got my wife in the ground and they’re up there partying and talking to each other every day and reminiscing, if you want to call it that.”

Bernard said he thought his son would one day become a general contractor. He still calls him Scotty, even at Elmira. He said he blamed himself for their situation. “As the dad, I should have known better,” he said. “I made decisions and choices with my heart instead of my head. That’s basically what it comes down to. I knew better.”

When their first parole hearing comes up, in April 2020, Scott will be 51 and his father 78.

Until then, there are the days on G Block. Scott Peters is part of a prison garbage crew, while Bernard is the veterans’ affairs coordinator for inmates who served in the military. In the evenings, they are busy participating in various programs, including the crochet club, whose members make and donate mittens, scarves and lapghans to nearby charitable groups each winter.

One day in January, Scott was in their cell when he received word that he had a visitor. His son, Scott, had brought along the newest member of the Peters family, his 4-month-old son, Jaden. All of Scott’s five grandchildren were born while he has been in prison. “First thing he did,” Scott said of his infant grandson with a laugh, “he’s going for the beard. Whomp. We were fighting over the beard.”

Scott held the baby for a while in the visiting room. His father did, too. Scott and Bernard Peters were there, together.