| Want to send this page or a link to a

friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

Another

School Barrier for African Girls: No Toilet |

________________ |

|

|

By SHARON

LaFRANIERE |

|

|

|

|

|

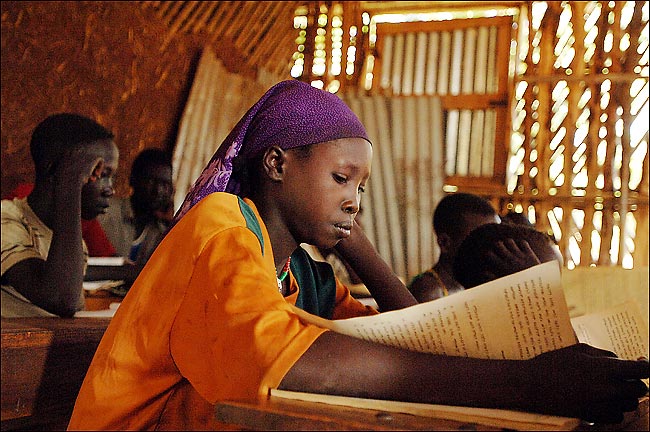

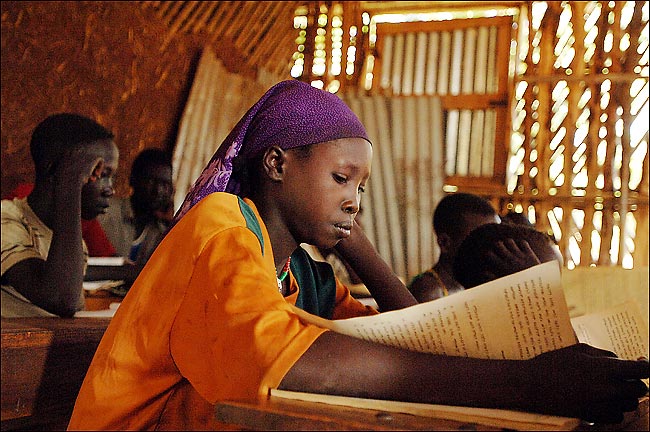

Vanessa Vick for The New York Times |

| Fatimah Bamun, 14, is the only girl in her fourt-grade class in

Balizenda, Ethiopia, where a lack of sanitation threatens education for girls. More

Images / Related text: Slavery in the

family |

BALIZENDA, Ethiopia - Fatimah Bamun dropped out of Balizenda Primary School in first

grade, more than three years ago, when her father refused to buy her pencils and paper.

Only after teachers convinced him that his daughter showed unusual promise did he relent.

Today Fatimah, 14, tall and slender, studies math and Amharic, Ethiopia's official

language, in a dirt-floored fourth-grade classroom.

Whether she will reach fifth grade is another matter. Fatimah is facing the onset of

puberty, and with it the realities of menstruation in a school with no latrine, no water,

no hope of privacy other than the shadow of a bush, and no girlfriends with whom to

commiserate. Fatimah is the only girl of the 23 students in her class. In fact, in a

school of 178 students, she is one of only three girls who has made it past third grade.

Even the women among the school's teachers say they have no choice but to use the

thorny scrub, in plain sight of classrooms, as a toilet.

"It is really too difficult," said Azeb Beyene, who arrived here in September

to teach fifth grade. Here and throughout sub-Saharan Africa, schoolgirls can only

empathize. In a region where poverty, tradition and ignorance deprive an estimated 24

million girls even of an elementary school education, the lack of school toilets and water

is one of many obstacles to girls' attendance, and until recently was considered unfit for

discussion. In some rural communities in the region, menstruation itself is so taboo that

girls are prohibited from cooking or even banished to the countryside during their

periods.

But that impact is substantial. Researchers throughout sub-Saharan Africa have

documented that lack of sanitary pads, a clean, girls-only latrine and water for washing

hands drives a significant number of girls from school. The United Nations Children's

Fund, for example, estimates that one in 10 school-age African girls either skips school

during menstruation or drops out entirely because of lack of sanitation.

The average schoolgirl's struggle for privacy is emblematic of the uphill battle for

public education in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly among girls. With slightly more than

6 in 10 eligible children enrolled in primary school, the region's enrollment rates are

the lowest in the world.

Beyond that, enrollment among primary school-aged girls is 8 percent lower than among

boys, according to the United Nations Children's Fund, Unicef. And of those girls who

enroll, 9 percent more drop out before the end of sixth grade than boys.

African girls in poor, rural areas like Balizenda are even more likely to lose out. The

World Bank estimated in 1999 that only one in four of them was enrolled in primary school.

The issue, advocates for children say, is not merely fairness. The World Bank contends

that if women in sub-Saharan Africa had equal access to education, land, credit and other

assets like fertilizer, the region's gross national product could increase by almost one

additional percentage point annually. Mark Blackden, one of the bank's lead analysts, said

Africa's progress was inextricably linked to the fate of girls.

"There is a connection between growth in Africa and gender equality," he

said. "It is of great importance but still ignored by so many."

The pressure on girls to drop out peaks with the advent of puberty and the problems

that accompany maturity, like sexual harassment by male teachers, ever growing

responsibilities at home and parental pressure to marry. Female teachers who could act as

role models are also in short supply in sub-Saharan Africa: they make up a quarter or less

of the primary school teachers in 12 nations, according to the United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Florence Kanyike, the Uganda coordinator for the Forum of Women Educationalists, a

Nairobi-based organization that lobbies for education for girls, said the harsh

inconvenience of menstruation in schools without sanitation was just one more reason for

girls to stay home.

They miss three or four days of school," she said. "They find themselves

lagging behind, and because they don't perform well, their interest fails. They start to

think, 'What are we doing here?' The biggest number of them drop out in year five or

six."

Increasingly, international organizations, African education ministries and the

continent's fledgling women's rights movements are rallying behind the notion of a

"girl friendly" school, one that is more secure and closer to home, with a

healthy share of female teachers and a clean toilet with a door and water for washing

hands.

In Guinea, enrollment rates for girls from 1997 to 2002 jumped 17 percent after

improvements in school sanitation, according to a recent Unicef report. The dropout rate

among girls fell by an even bigger percentage. Schools in northeastern Nigeria showed

substantial gains after Unicef and donors built thousands of latrines, trained thousands

of teachers and established school health clubs, the agency contends.

Ethiopia has also made strides. More than 6 in 10 girls of primary-school age are

enrolled in school this year, compared with fewer than 4 in 10 girls in 1999. Still, boys

are far ahead, with nearly 8 in 10 of them enrolled in primary school.

Unicef is building latrines and bringing clean water to 300 Ethiopian schools. But more

than half of the nation's 13,181 primary schools lack water, more than half lack latrines

and some lack both. Moreover, those with latrines may have just one for 300 students,

Therese Dooley, Unicef's sanitation project officer, said. In theory, at least, outfitting

Ethiopia's schools with basic facilities can be cheap and simple, she said. Toilets need

be little more than pits and concrete slabs with walls and a door; rain can be trapped on

a school's roof and strained through sand.

Still, she said, toilets for boys and girls must be clearly separate and students who

may have never seen a latrine must be taught the importance of using one. And the toilets

must be kept clean, a task that frequently falls to the very schoolgirls who were supposed

to benefit most.

In Benishangul Gumuz Province in western Ethiopia, where low mountains rise over

brilliant yellow fields of oilseeds, such amenities are rare indeed. Guma, a town of

13,000 about an hour's drive from Balizenda over a viciously rutted road, has water only

sporadically. The town's main street is dotted with shops, but not one sells sanitary

pads. Few residents could afford them anyway. Women make do with folded rags.

Balizenda primary school, with 178 students, is a long, litter-strewn building in a

dirt clearing surrounded by brush. Two lopsided reed-walled huts pass for fifth- and

sixth-grade classrooms. On the playground soccer field, three tree limbs lashed together

form the goal.

With the exception of the first grade, where girls are more than a third of the pupils,

Balizenda could be mistaken for an all-boys' school. Only 13 girls are enrolled in grades

two through six, and even that is an improvement over three months ago.

"When I came here in September, there was not a single female student" in the

entire school, said Tisge Tsegaw, 22, the first-grade teacher. "We went to the homes

and motivated the parents, and then they came."

But in many cases, not for long. "The parents prioritize. They figure if the girls

stay home, they can do the grinding, help with the harvesting, fetch the water and collect

the firewood," Ms. Tsegaw said. "They agree to enroll them. Then after two

months, they take them back."

The school's latrine, a hovel of thatch and reeds, fell down last year. Yehwala Mesfin,

the school's director, said neither the villagers nor the Education Ministry would help

build a new one. Parents viewed their annual rebuilding of the reed-walled fifth- and

sixth-grade classrooms as a sufficient contribution, he said.

Ms. Beyene, the fifth-grade teacher who arrived here in September, said she agreed to

stay at Balizenda only after Mr. Mesfin promised that she could use a toilet at a health

center nearby. But since then, the health center has been closed for lack of staff.

"The majority of time I use the open field," she said. "There is no

privacy. Everybody comes, even the students. So we try to restrict ourselves to urinate

before school and at nighttime. I already have a kidney infection because of this. My

situation is getting worse."

The school's only sixth-grade girls, Mesert Mesfin, 17, and Worknesh Anteneh, 15, said

that when they could not resist nature's call, they stood guard for each other in the

field. When her period began one recent Thursday morning, Mesert said, she had no choice

but to run home. Worknesh said she sometimes avoided school during her period.

"It is really a shame," she said. "I am really bothered by this."

Fatimah Bamun, who started school so late that at 14 she is only in fourth grade, said

she did not want to miss a single class because she wanted to be a teacher. But, she

added, she does not have a lot of backing from her friends.

"I have no friend in the class," she said. "Most of my friends have

dropped out to get married. So during the break, I just sit in the classroom and

read."

Her father, however, now says he is fully behind her. "The people from the

government are all the time telling us to send our daughters to school, and I am listening

to these people," he said.

Neither Fatimah's older sister nor mother went to school. And Fatimah is all too

familiar with the alternatives for illiterate girls. When she returns home after school

each day, she is greeted by another girl, named Eko, who lives in her hut. Thin and poorly

dressed, 12 years old at most, Eko is literally a wedding present, given to the Bamuns

when Fatimah's sister married Eko's brother.

Before the wedding, Eko was an avid second grader. "I liked school very much; it

would have been better to stay in school," she said quietly, picking at her callused

hands. Now she is the Bamun family servant, up at sunrise to pound sorghum with a stone

for the breakfast porridge. Her education is vicarious.

"She always asks me, 'When are you going to school?' " Fatimah said. "

'What do you do there? What subjects do you study?' "

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times,

International, of Friday, December 23,

2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of

democracy and human rights |