PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — In 2010, Daphne Joseph, a slim, shy teenager, took a pounding from life.

A Year Later, Haiti Struggles Back

|

By DEBORAH SONTAG |

Damon Winter/The New York Times

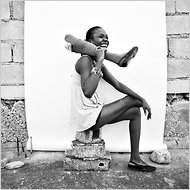

Fabienne Jean, a dancer who lost a leg in the 2010 quake in Haiti, now has a prosthetic limb. Dance makes up part of her exercise routine.

She watched with horror as her mother’s mangled body was carted off in a wheelbarrow after the Jan. 12 earthquake. She fell in with a ragtag group of orphans taken under the wing of a well-meaning but ill-equipped community group. She left them unwillingly when a self-proclaimed relative took her away to use her as a servant.

And then last fall, not long before her 15th birthday, Daphne found herself in an actual home, reunited with the other orphans stranded after the disaster they all call “goudou-goudou” for the terrible sound of the ground shaking. She wore a party dress; she blew out candles; she smiled.

“I believe that Daphne was a fragile, sensitive girl even before ‘goudou-goudou,’ ” said Pierre Joseph, a psychologist who counsels her. “After, she was like a glass that got filled to the brim and then overflowed. You could say she is still in shock. But she is finding her equilibrium.”

After a year of almost unfathomable hardship in Haiti, there is little reason to be hopeful now.

More than a million displaced people still live under tents and tarpaulins. Reconstruction, of the build-back-better kind envisioned last March, has barely begun. Officials’ sole point of pride six months after the earthquake — that disease and violence had been averted — vanished with the outbreak of cholera and political unrest over a disputed presidential election.

And indeed, for some, misery is a constant. Rose, a young woman abducted, repeatedly raped and torturously stashed in earthquake ruins last June, was forced to flee to the countryside after her kidnappers made a second attempt. Marie Claude Pierre, whose son was whisked abroad in an orphan airlift, was sad even before the earthquake. She is sadder now.

Yet despite this gloomy backdrop, many Haitians, like Daphne, have started to find some equilibrium — to heal, to rebuild or simply to readjust their sights. A dancer whose leg was amputated is walking on a new limb. A pastor whose church was devastated is reveling in a congregation doubled in size. A businessman, stubbornly loyal to Haiti, is opening an earthquake-proof factory where his old one collapsed.

Here, haunting and hopeful, are some of their stories.

Fabienne Jean

Fabienne Jean, the dancer who lost a leg in the earthquake, smiled so radiantly and expressed such courage that everybody who met or read about her wanted to help. Doctors, prosthetists, choreographers, dancers with disabilities, charitable groups — they all aspired to adopt Ms. Jean.

By early spring, Ms. Jean was struggling with conflicting offers: to be fitted here for a prosthetic limb by a New Hampshire nonprofit group or to fly to New York, where Mount Sinai Medical Center would provide corrective surgery, rehabilitation and a stay of months in the city. The foreigners’ attention was overwhelming.

After a period of agonizing indecision, Ms. Jean chose to stay in Haiti, where she felt at home. The New Yorkers were proposing a second operation to strengthen her stump. That, Ms. Jean said, was a deal-breaker. “I didn’t want another operation,” she said. “I didn’t want to lose any more of my leg.”

Recently, standing proudly on two feet, Ms. Jean led the way into her family home. Always fashion-conscious, she was wearing chunky jewelry, a spaghetti-strap tunic top and slim jeans. Her new limb, ending in a stockinged foot encased in a delicate slingback flat, peeked out from beneath the cuff. Using a cane, she gracefully, but with a slight limp, navigated the house’s challenging terrain — a sloped, rutted entryway and unfinished concrete stairs without banisters.

Ms. Jean had moved back in with her extended family after breaking up with her longtime boyfriend, also a dancer, for “reasons of the heart, nothing to do with the leg,” she said. About a week ago, she proudly settled into a rental apartment of her own, which she shares with her mother and her young daughter (a niece whom she had adopted before the earthquake).

Several times a week, Ms. Jean does pliés and arabesques as part of an exercise routine overseen by a high school senior trained as a physical therapy assistant by the New Hampshire group. That group, the Nebco Foundation, which built and fitted her limb, will be fine-tuning the socket next month and testing out feet that will allow her to dance again.

Ms. Jean looks forward to that, she said, but she added: “Realistically, there is no way I’ll be a professional performer again. So I will need another way to make a living.” She envisions a fashion boutique or a dance school.

Ms. Jean said that she did not want to be a drain on her family, which had always expected her, the oldest child and the most talented, to support them. Her father, she said, was scared after the earthquake that she would end up “in a corner, like a handicapped person.” But that is not going to happen, she said.

“There are some disabled people who think that life is over, who are ashamed,” she said, before jauntily swinging her prosthesis over her shoulder during a photo shoot. “I’m not like that. Except for the fact that I lost a part of myself on Jan. 12, I’m still Fabienne.”

The Rev. Enso Sylvert

As if he had not budged since the earthquake, the Rev. Enso Sylvert sat one recent morning on the same metal chair under the same tarpaulin, now ripped, where he held court after the disaster.

In the shadow of his collapsed church on Avenue Poupelard, Pastor Sylvert was still sporting a blazing orange shirt and wrinkled yellow tie, still preaching about the end of times.

But his vow to rebuild in 2010 had been tempered by reality. The bank recently foreclosed on the property after he fell disastrously behind on loan payments because his parishioners could not afford donations. Any day now, he said, the bank will be seizing what remains of the church.

Still, the pastor insisted, just as his chorus narrowly escaped death when the church fell, just as his daughter was spared when she stood to answer a teacher’s question while the girl who slid into her seat was killed by a concrete block, so, too, would “a miracle” keep the Evangelical Church of Grace alive.

“I am certain — certain! — that we will rise again on Avenue Poupelard,” he said. “The events of Jan. 12 destroyed hundreds of church buildings. But did they kill our churches? Ah, no. Au contraire. We don’t need roofs to pray. God is our cover.”

Beyond the church, the survivalist spirit along the hard-hit Avenue Poupelard, which pulsed so brightly right after the earthquake, chugs along wearily. People are resourceful, the pastor said, “but they carry their losses inside like nagging sorrows.”

Pastor Sylvert holds open-air services on property adjoining the church, and many are lured by the oversize speakers that blast his fiery preaching. But misery itself has been good for business, he said.

“In moments like this, with destruction all around, with electoral crisis in the air, with cholera in the water, people have only God,” he said. “God is Haiti’s only uncorrupted leader.”

Marie Claude Pierre

Deep inside a maze of alleyways in the Eternal City slum, Ms. Pierre, 30, shyly welcomed visitors into the one-room shanty that she shares with a dozen relatives — but not with any of her children.

Ms. Pierre’s oldest son, Fekens, 11, has been living at a Pittsburgh-area orphanage since a week after the earthquake, when he was plucked from Haiti aboard an orphan airlift engineered by Gov. Edward G. Rendell of Pennsylvania. As it turned out, several of the other children on that flight were not orphans, either, and did not have adoptive parents waiting for them.

Images of the children’s landing in Pittsburgh were broadcast worldwide, but Ms. Pierre did not know Fekens was gone until days after he left. By the time she made her way through the disaster zone to the Bresma orphanage, where Fekens and the others had been staying, it was empty. When she finally learned why, what troubled her most, she said, was that Fekens must have been trying to reach the cellphone she had lost in the earthquake to say goodbye.

A petite woman with tiny studs embedded in her front teeth, Ms. Pierre described herself as accepting without protest whatever life dealt her. Speaking softly in a shack dominated by a bookshelf cluttered with stuffed animals, she explained how she had first come to lose custody of Fekens — and her four other children.

She and her ex-husband used to fight, she said, and she would flee, battered, to relatives’ homes. During one separation, her husband “made the decision to give away our children,” she said. She was granted no say, she said, but she imagined that their stay at Bresma, which she visited monthly, would be temporary.

It was, although not in the way she had expected. Four of her children were adopted by a French family before the earthquake, according to the orphanage director, Margarette St. Fleur. Only Fekens, the oldest, remained at Bresma, and “Fekens wanted to be adopted, too,” Ms. St. Fleur said.

When the earthquake struck, leaving the orphanage damaged but standing, two Pittsburgh-area women devoted to Bresma’s children sent out an urgent appeal for their rescue, which Governor Rendell answered.

After the plane landed in Pittsburgh, the federal Department of Health and Human Services assumed legal custody of a dozen children, including Fekens, who were not in the midst of adoption proceedings. Then, in early December, the children were all cleared for adoption. Not long before that, Ms. Pierre said, Ms. St. Fleur had asked her to sign papers relinquishing her parental rights. She did.

Ms. Pierre said that she missed her children. “I hope that one day they will return to visit me,” she said. She requested that a message be given to Fekens: “Tell him bonjour, bonsoir. Tell him to behave and not to make problems. Send him kisses.”

Asked if that were all, she hesitated. “I know he is not working,” she said of her 11-year-old, “so I cannot ask him to wire me money.”

Alain Villard

A few days after the earthquake, Alain Villard, shaking his head, surveyed the tree-shaded property in Pétionville where his boutique hotel, Villa Thérèse, lay in ruins. Ten had died there, including four Haitian children and the foreign parents who were adopting them. Several bodies lay bundled in cloth, swarming with flies.

Down in Carrefour, Mr. Villard’s large garment factory, Palm Apparel, had been flattened, and the death toll appeared to be in the hundreds. A worker’s putrefying corpse dangled out the window from which she had tried to leap to safety.

At the time, talking 20 feet from the wrapped corpses, Mr. Villard, 42, had mused wistfully about how Haiti’s depressed economy had been poised for revitalization. Surely, he said, there must be a way to recapture that momentum.

With most of Haiti paralyzed by the disaster, Mr. Villard rushed single-mindedly forward. Within a month, he had cleared the debris and human remains from his factory, which produces T-shirts for a Canadian apparel company, in time for a memorial service.

It turned out that far fewer workers had been killed than originally estimated. Sixty-seven were mourned at the service, at the end of which Mr. Villard announced the factory’s reopening at 6:30 a.m. the following Monday, with double shifts operating in the surviving buildings.

“I believe in manufacturing,” he said recently. “As a businessman under contract to a multinational company, I need to ship product. And the Haitian people need to work.”

When he spoke, at a garden table on his deserted hotel property, Mr. Villard had just returned from a trip abroad to find the country shuttered because of political unrest. “2010 — the year that Haiti was pounded with headaches,” he said.

He expects to open a new, more earthquake-proof factory on Jan. 12, and to break ground for the hotel’s reconstruction, too. Although it disappeared almost a year ago, Villa Thérèse is still ranked second of 25 hotels in Port-au-Prince on the Tripadvisor Web site — a sad commentary on Haiti’s tourism industry.

But, Mr. Villard said: “You have to keep the faith. Under no circumstances would I have packed my bags and left Haiti like others did. Yes, I could go somewhere else that has nice, paved roads and electricity. But no country is perfect. And, hey, we’ve got mangos — organic mangos.”

Daphne Joseph

Daphne was deposited in January at the doorstep of an idealistic community organization called Frades, which specialized in microloans but accepted several dozen orphaned or stranded children because it seemed like the honorable thing to do.

In the spring, a young woman with little connection to her — Daphne’s half-brother’s father’s girlfriend — showed up to claim her and moved her into a squalid tent city.

Daphne, twisting her hands as she recounted her time there, said the woman used to beat her with a rough leather belt if she hesitated or refused to fetch water or empty the chamber pot. She longed to return to Frades, although the situation there was hardly ideal.

By early summer, the children were sleeping on shredded carpet remnants atop a concrete slab under disintegrating tents. They faced imminent eviction. But, just when things were truly desperate, a group of concerned Americans, and especially one very generous donor, came to the rescue. The Americans helped the Haitian group rent a nice house on a walled property, hire cooks and teachers, secure a generator and stock treated water, provisions and toys.

The Rev. Gerald Bataille, the children’s full-time guardian since January, organized a makeshift school and a household staff. The 13 boys share one bedroom with two beds, the 15 girls another. New backpacks hang, empty, on the walls. (“We don’t yet have books to put in them,” the pastor explained.)

At mealtime, the children sit elbow to elbow on two long benches. After saying grace, they wave their little hands continuously over, say, their bowls of porridge to ward off the flies as they eat.

Once the group had settled in, Pastor Bataille sought to have Daphne, who looked increasingly thin and hollow-eyed, returned to Frades. But the woman refused. So he searched for and located Daphne’s mother’s brother, an actual relative who was shattered by his sister’s death.

“The uncle gave Daphne back to us until she reaches the age of maturity,” the pastor said, adding, “And since that day, he has not once come back to see how she is.”

Daphne still has recurring nightmares and crying jags; she disappears into herself without warning. But she is devoted to her studies — an evaluation found her at a fourth-grade level — and she is loving to and loved by the other children.

“They are like my brothers and sisters,” said Daphne, wearing a lacy headband and a “Cheerleader!” T-shirt. She added that she used to tell her mother that she dreamed of opening an orphanage someday for children who were not as lucky as her.

“My mom would say: ‘Oh, you have big dreams. You will have to be a good girl — stay chaste and pray to God — to realize your goal,’ ” Daphne said. “My mom also used to say, ‘I will always be by your side.’ She is not. But goudou-goudou didn’t take away my dream.”

Copyright 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, International, of Tuesday, January 4, 2011.