| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted August 30, 2003 |

A Deep Crisis, Shallow Roots |

|

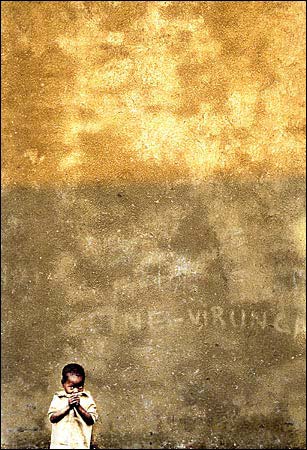

Mikkel Ostergaard/Panos Pictures |

| A Rwandan refugee child in Zaire, in 1994. A new book argues that the region's so-called "ancient hatreds" are a colonial creation. |

By JOHN SHATTUCK |

|

IN central Africa, a genocidal war has raged for nearly a decade, costing more than four million lives in Rwanda, Burundi and Congo and precipitating the worst humanitarian crisis in more than half a century. Central Africa shares this gruesome recent past with southeastern Europe, where in the 1990's the Balkans were swept by a wave of killing and "ethnic cleansing." In both cases, genocide was widely misunderstood to be the inevitable product of "ancient hatreds." Advertisement

Jean-Pierre Chrétien, a French historian with vast experience in the Great Lakes region of Africa, has undertaken the formidable task of tracing the roots of the region's violence and exposing the ideological myths on which the ancient-hatreds theory rests. In a monumental study that marches through two millenniums before approaching central Africa's contemporary agony, Mr. Chrétien punctures the sense of inevitability that permeates our thinking about the Rwandan genocide.

Along the way, he illuminates the responsibility of a wide range of actors from the colonial period through the present. As warlords continue today to compete for power in a thoroughly ravaged Congo, Mr. Chrétien helps us understand how this all came about and why it matters that we know.

The story begins with the geography of the central African highlands. Despite its equatorial location, Mr. Chrétien says, "the region is blessed with good climate, is rich with diverse soils and plants, and has prospered thanks to some strong basic techniques: the association of cattle keeping and agriculture; the diffusion of the banana a millennium ago; and the mastery of iron metallurgy two millennia ago." In this healthy environment, complex social structures evolved in which the idea of kingship and strong central authority took hold and flourished for more than 300 years before the arrival of colonial powers in the mid-19th century.

The fertile lands around the Great Lakes were settled by indigenous Hutu cultivators, while the more mountainous areas were used for the raising of cattle by Tutsi pastoralists. In the early kingdoms of the region, agricultural and pastoral systems were integrated because they controlled complementary ecological zones and served mutually beneficial economic interests. As Mr. Chrétien argues convincingly, nowhere at this time could the "social dialectic be reduced" to a Hutu-Tutsi cleavage.

That began to change in the 19th century. As social structures became more complex, the success of the central African kingdoms depended increasingly on territorial expansion through raiding, colonizing and annexing of neighboring lands. At the same time, Tutsi cattle raisers in search of more land began to emerge as a new elite and a driving force behind expansion. The kingdoms of Rwanda and Uganda were particularly expansionist, but were soon thwarted by the arrival of colonial powers. The immediate effect of colonialism was to reorient the stratified and dynamic societies of the Great Lakes around competing poles of collaboration with, and resistance to, the new foreign occupiers.

Since these remote societies had been untouched by the slave trade that ravaged Africa's coastal regions, they presented the Europeans with a range of robust aristocracies and royal courts to win over.

At this crucial point, the issue of race entered the picture. Obsessed by their theories of racial classification, 19th- and early-20th-century Europeans rewrote the history of central Africa. Imposing their own racist projection of superiority on Tutsi "Hamito-Semites" and a corresponding inferiority on Hutu "Bantu Negroes," missionary and colonial historians began to attribute the rise of the Great Lakes kingdoms to the arrival of a superior race of "black Europeans" from the north.

Mr. Chrétien quotes many examples of this toxic "scientific ethnicism," which the Belgians purveyed to their central African colonies until just before independence. A typical example from a colonial school newspaper in Burundi in 1948 states that "the preponderance of the Caucasian type is deeply marked" among the Tutsi, making them "worthy of the title that the explorers gave them: aristocratic Negroes."

Anointed by the Belgians as their administrators and collaborators in Rwanda and Burundi, the Tutsis, who never constituted more than 18 percent of the population, were presented with a poisoned chalice combining ethnic elitism with economic favoritism.

In educating their chosen elites, the Belgians were relentlessly racist. Starting in 1928, all primary schools in Rwanda were segregated, while at the secondary-school level Rwandan (and later Burundian) Tutsis were three to four times better represented than Hutus.

Not surprisingly, the majority Hutu population chafed at this discrimination, and in the late 1950's a Hutu counter-elite began calling for the end of "Tutsi feudalism." On the eve of independence, the growing Hutu rebellion was backed, in a catastrophic reversal, by the Roman Catholic Church and the colonial administration, which now claimed that the Hutu majority represented "democratic values." The outcome, as Mr. Chrétien shows, was that "the new Rwanda declared its national past `Tutsi' and thus despicable."

The post-colonial period was marked by a zero-sum ethnic fundamentalism that destroyed the social fabric. Mr. Chrétien argues that "the generation catapulted to the top of the former kingdoms thus squandered the opportunity offered by independence." The deep ethnic insecurities created by European rewriting of African history made the competing ethnic groups far more concerned about their own survival than about the task of nation-building. As a result, he writes, the elites were "haunted by a passion — which some admitted and others covered up — about the supremacy of their ethnic group." In Rwanda, the Hutu revolution led to a series of pogroms against the Tutsi minority, culminating in the 1994 genocide.

Thus, modern hatreds, not ancient ones, destroyed Rwanda. Far from being inbred in the country's ancient social structures, these destructive animosities were created during its recent colonial past. Even then, it took the manipulation of ethnic identity by the country's new elites to produce the atmosphere of fear and recrimination that expanded through the Rwandan countryside and later into vast reaches of Congo in the genocidal war that has gripped the region for nearly a decade.

In this respect, the Rwandans were no different from Slobodan Milosevic, Franjo Tudjman and the other authors of ethnic cleansing in the Balkans. But the world has so far done far less to confront them, and Mr. Chrétien's extraordinary book prompts one to wonder whether the reason is rooted in the racism reflected in the violent rewriting of central African history.

Copyright The New York Times Company. Reproduce from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of August 30, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |