| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted August 13, 2007 |

| WORD FOR WORD/NEW RUSSIAN HISTORY |

|

|

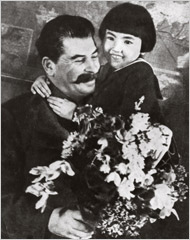

Henry Guttman/Getty Images |

|

| EMBRACE AND EXILE Stalin with a girl who later in life was sent to the gulag. | |

| Yes, a Lot of People Died, but ... |

| By ANDREW E. KRAMER |

STALIN has undergone a number of transformations of his historical image in Russia, interpretations that say as much about the country’s current leaders as about the dictator himself.

In the West, Stalin is remembered for the numbers of his victims, about 20 million, largely his own citizens, executed or allowed to die in famines or the gulag. They included a generation of peasant farmers in Ukraine, former Bolsheviks and other political figures who were purged in the show trials of the 1930s, Polish officers executed at Katyn Forest, and Russians who died in the slave labor economy. Stalin’s crimes have been tied to his personality, cruelty and paranoia as well as to the circumstances of Russian and Soviet history.

While not denying that Stalin committed the crimes, a new study guide in Russia for high school teachers views his cruelty through a particular, if familiar, lens. It portrays Stalin not as an extraordinary monster who came to power because of the unique evil of Communism, but as a strong ruler in a long line of autocrats going back to the czars. Russian history, in this view, at times demands tyranny to build a great nation.

The text reinforces this idea by comparing Stalin to Bismarck, who united Germany, and comparing Russia in the 1930s under the threat of Nazism to the United States after 9/11 in attitudes toward liberties.

| THE HISTORY GRADE |

— titled “A Modern History of Russia: 1945-2006”

— was presented at a conference for high school teachers where President Vladimir V. Putin spoke; the author, Aleksandr Filippov, is a deputy director of a Kremlin-connected think tank. Excerpts from the guide follow. The text was translated by Nikolai Khalip and Michael Schwirtz in Moscow.

| JUST LIKE BISMARCK AND PETER |

As a result of the “Big Purge” of late 1930s, practically all members and candidates to become Politburo members elected after the 17th Party Congress suffered from reprisals to a certain degree....Postwar reprisals were quite similarly addressed... The number of victims of the Leningrad case reached about two thousand people. Many of them faced firing squads. Studies by Soviet and foreign historians confirmed that the ruling class was the priority victim of the repressions in 1930-1950. ...

Stalin followed Peter the Great’s logic: demand the impossible from the people in order to get the maximum possible. ...The result of Stalin’s purges was a new class of managers capable of solving the task of modernization in conditions of shortages of resources, loyal to the supreme power and immaculate from the point of view of executive discipline....

Thus, just like Chancellor Bismarck who united German lands into a single state by “iron and blood,” Stalin was reinforcing his state by cruelty and mercilessness. Strengthening the state, including its industrial and defensive might, he considered one of the main principles of his policy.

Indirect evidence of this can be found in the memoirs of his daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva. Every time he looked at her dress he always asked the same question, making a wry mouth: “Is this foreign-made?” and always cracked a smile when I answered, ‘No, it was made here, locally.”

| A STRONG IF CRUEL LEADER |

A chapter ends with a brief broadening of the interpretation that hints at ways to discuss Stalin’s personal flaws, and the fate of the millions of Soviet citizens who suffered and perished under his rule. But little detail is supplied on that last point, nor does the guide suggest how teachers might conduct more research on it. ...

It is common knowledge that power corrupts. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. It is well known from Russian history how corrupting a long term in power is. Biographies of such outstanding rulers as Peter the First and Catherine the Second prove it ...

The leader’s closest associate, V. M. Molotov, admitted that at the beginning Stalin struggled with his cult, but later on he developed a liking for it: “He was very reserved in the first years, and then he put on airs.”

As to what people think of Stalin, we can judge by an opinion poll conducted in February 2006 by Public Opinion Fund:

If we speak as a whole of the role of Stalin in Russian history, was he positive or negative? Positive: 47 percent; negative: 29 percent; did not answer: 24 percent.

Thus, there are grounds for controversial assessments of Stalin’s role. On the one hand, he is considered one of the most successful leaders of the U.S.S.R. During his leadership the territory of the country was expanded and reached the boundaries of the former Russian Empire (in some areas even surpassed it). A victory in one of the greatest wars was won; industrialization of the economy and cultural revolution were carried out successfully, resulting not only in the great number of educated people but also in creating the best educational system in the world. The U.S.S.R. joined the leading countries in the field of science; unemployment was practically defeated.

But there was a different side to Stalin’s rule. The successes — many Stalin opponents point it out — were achieved through cruel exploitation of the population. The country lived through several waves of major repressions during his rule. Stalin himself was the initiator and theoretician of such “aggravation of class struggle.” Entire social groups were eliminated: well-off peasantry, urban middle class, clergy and old intelligentsia. In addition, masses of people quite loyal to the authorities suffered from the severe laws.

| ECHOES OF 9/11 |

The study guide pointedly refers to what it says are recent restrictions on American liberties undertaken to fight terrorism.

Political and historical studies show that when they come under similarly serious threats, even “soft” and “flexible” political systems, as a rule, turn more rigid and limit individual rights, as happened in the United States after September 11, 2001.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, of Sunday, August 12, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |