| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted November 23, 2008 |

| Week in Review |

| The Nation |

| Will the Safety Net Catch Economy's Casualties? |

|

|

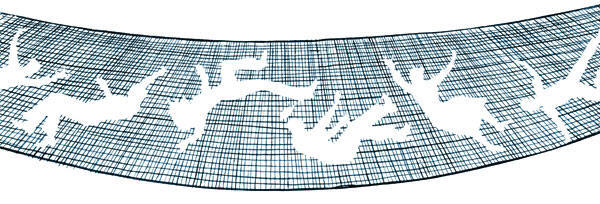

| ALEX NABAUM | |

|

|

| By STEVEN GREENHOUSE |

|

|

|

|

|

| ALEX NABAUM | |

|

|

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |