On a chilly night in the dead of a New England winter, Yasir Qadhi hurried down the stairs of Yale University’s religious-studies department, searching urgently for a place to make a private call. A Ph.D. candidate in Islamic studies, Qadhi was a fixture on the New Haven campus. He wore a trim beard and preppy polo shirts, blending in with the other graduate students as he lugged an overstuffed backpack into Blue State Coffee for his daily cappuccino. A popular teaching assistant, he exuded a sprightly intensity in class, addressing the undergraduates as “dudes.”

Why Yasir Qadhi Wants to Talk About Jihad

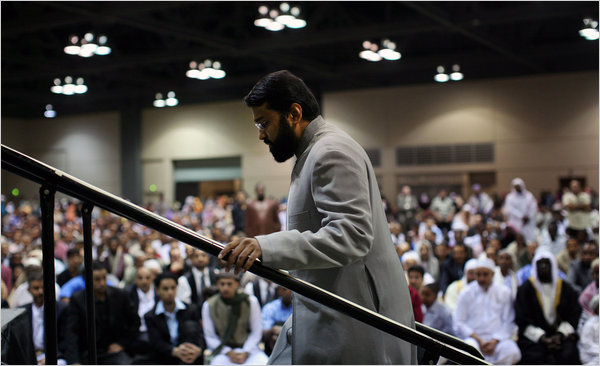

Yasir Qadhi spoke before the Eid al-Fitr prayer service in September at the Memphis Cook Convention Center.

By ANDREA ELLIOTT

Multimedia

Jerry Lemenu/EPA/Corbis

Underwear Bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab in federal court in Detroit on Jan. 25. His trial is scheduled to begin on Oct. 4.

But Qadhi had another life. Beyond the gothic confines of Yale, he was becoming one of the most influential conservative clerics in American Islam, drawing a tide of followers in the fundamentalist movement known as Salafiya. Raised between Texas and Saudi Arabia, he seemed uniquely deft at balancing the edicts of orthodox Islam with the mores of contemporary America. To many young Muslims wrestling with conflicts between faith and country, Qadhi was a rock star. To law-enforcement agents, he was also a figure of interest, given his prominence in a community considered vulnerable to radicalization. Some officials, noting his message of nonviolence, saw him as an ally. Others were wary, recalling a time when Qadhi spouted a much harder, less tolerant line. On this night, however, it was Qadhi’s closest followers who were questioning him.

Two weeks earlier, on Christmas Day 2009, a young Nigerian tried to blow up a jet headed for Detroit with a bomb sewn into his underwear. The suspect had been a student of Qadhi’s at the AlMaghrib Institute, which teaches Salafi theology in 21 American cities. F.B.I. agents were demanding interviews with Qadhi’s students. He urged them to cooperate, but many pushed back, and Qadhi found himself caught between two seemingly irreconcilable forces: a deeply suspicious government and a young following he could lose.

In the basement of the religious-studies building, Qadhi settled into an empty room, flipped open his MacBook Pro (encased in Islamic apple green) and dialed in to an Internet conference call with more than 150 of his AlMaghrib students. “I want to be very frank here,” Qadhi said, his voice tight with exasperation. “Do you really, really think that blowing up a plane is Islamic? I mean, ask yourself this.”

None of the students defended the plot, but some sympathized with the suspect, said several students who participated in the call, one of whom provided a recording to The Times. Was it not possible, they asked, that he had been set up? And how could they trust the F.B.I. after all they experienced — the post-9/11 raids, the monitoring of mosques, the sting operations aimed at Muslims? A few went as far as to say that they could not turn against a fellow Muslim who was trying to fight the oppressive policies of the United States.

Qadhi paced the worn, gray carpet. “There were even Muslims on that plane!” he said. “I mean, what world are you living in? How angry and overzealous are you that you simply forget about everything and you think that this is the way forward?”

Over the next year, Qadhi was thrust into the center of a crucial struggle — for the minds of his young students, the trust of his government and his own future as America was waking to a new threat. Since 2008, more than two dozen Muslim-Americans have joined or sought training with militant groups abroad. They are among the roughly 50 American citizens charged with terrorism-related offenses during that time. These suspects are a mixed lot. Some converted to Islam; others were raised in the faith. They come from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and have migrated to different fronts in their global war, from Somalia to Pakistan. Their motivations differ, but the vast majority share two key attributes: a deep disdain for American foreign policy and an ideology rooted in Salafiya.

In the spectrum of the global Salafi movement, Qadhi, who is 36, speaks for the nonmilitant majority. Yet even as he has denounced Islamist violence — too late, some say — a handful of AlMaghrib’s former students have heeded the call. In addition to the underwear-bomb suspect, the 36,000 current and former students of Qadhi’s institute include Daniel Maldonado, a New Hampshire convert who was convicted in 2007 of training with an Al Qaeda-linked militia in Somalia; Tarek Mehanna, a 28-year-old pharmacist arrested for conspiring to attack Americans; and two young Virginia men held in Pakistan in 2009 for seeking to train with militants.

Qadhi said that none of those former students had approached him for counsel. But in recent years, countless others have come to him with questions about the legitimacy of waging jihad. “We’re finding ourselves on the front line,” Qadhi said. “We don’t want to be there.”

During the months I spent in the insular world of young American Salafis, it became clear how pressing those questions are for many conservative Muslims who have come of age after 9/11. They have watched as their own country wages war in Muslim lands, bearing witness — via satellite television and the Internet — to the carnage in Iraq, the drone attacks in Pakistan and the treatment of detainees at Guantánamo. While the dozens of AlMaghrib students I interviewed condemned the tactics of militant groups, many share their basic grievances. They are searching for the correct Islamic response, turning to the ancient texts that guide their American lives. Their salvation, they say, hangs in the balance.

This is what makes Qadhi such a pivotal figure in a subculture that is little understood, even by the law-enforcement officials who monitor it. He is the rare Western cleric fluent in the language of militants, having spent nearly a decade studying Islam in Saudi Arabia, steeped in the same tradition that spawned Osama bin Laden’s splinter movement. Arguably few American theologians are better positioned to offer an authoritative rebuttal of extremist ideology. But to do that, Qadhi says he would need to address the thorny question of what kinds of militant actions are permitted by Islamic law. It is a forbidden topic for most American clerics, who even refrain from criticizing their country’s foreign policy for fear of being branded unpatriotic.

For an ultraconservative cleric like Qadhi, the picture is more complicated. Engaging in a detailed discussion of militant jihad — a complex subject informed by centuries of scholarship — risks drawing the scrutiny of law enforcement and, Qadhi fears, possible prosecution. If he were to acknowledge that Islamic law endorses the legitimacy of armed resistance against Western forces in Muslim territory, he could give a green light to the very students he claims he is trying to keep off the militant path. Yet by remaining silent, Qadhi says he is losing the credibility he needs to persuade them of his ultimate message: those fights are not theirs, as Westerners, to fight. “My hands are tied, and my tongue is silent,” he said.

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

At Study Qadhi in the library at his home in suburban Memphis.

Multimedia

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

At Prayer Awaiting the completion of an Islamic center, Qadhi led a Ramadan prayer at a suburban Memphis church.

Militant clerics abroad have filled the void, none more than Anwar al-Awlaki, the American preacher who is now believed to be in hiding in Yemen with Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Awlaki has been linked to numerous plots against the United States, including the botched underwear bombing. He has taken to the Internet with stirring battle cries directed at young American Muslims. “Many of your scholars,” Awlaki warned last year, are “standing between you and your duty of jihad.”

It was near midnight last October when Qadhi’s teenage acolytes surrounded him at Thomas Sweet, an ice cream parlor in New Brunswick, N.J. Puma sneakers peeked out from under long robes. Suddenly the lyrics “shake your booty” blasted over the speakers. The young men leaned in closer, unfazed. Between helpings of mango-flavored sorbet, Qadhi pontificated on medieval Islamic theology. “We have a reasonable religion,” he said. “We’re a very logical, rational group of people.”

Qadhi’s students hang on his every word. They huddle around him — between classes, during meals, even in bathrooms — pinging him with questions. Their reliance on Qadhi is a product of contemporary Islam, a decentralized religion with no clear authority. Clerics with the highest level of scholarship are considered invaluable guides, especially in the secular West.

Qadhi was in New Jersey that weekend to teach a seminar on the concept of faith-led action. During a break, a dozen young men flocked to him once again. A soft-spoken engineer lobbed the first question: Wasn’t it hypocritical for the same Western imams who supported the Afghan resistance against the Soviets to now condemn the jihad against American troops? After all, another student asked, don’t civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan “have an obligation to do something to defend themselves?”

“I am not commenting on what they should or should not do,” Qadhi replied. “I am commenting on what you should do as American Muslims.”

They had heard it before: vote, educate your neighbors, protest peacefully. But is that what Islam commands when your people are dying? The question haunts some of Qadhi’s brightest students. One of the deepest Islamic principles is that of the ummah — the global community that unites all Muslims. The Prophet Muhammad was said to have likened it to the human body. If one part hurts, the whole body aches.

One of Qadhi’s followers, a feisty 27-year-old New Yorker, compared his experience of watching bombs fall on Iraq to what other Americans might feel at seeing “California being ravaged day in and day out. How would you feel?” He said he understood why Qadhi could not speak expansively about the conflicts overseas. Even so, he asked, who has greater credibility: the cleric living comfortably in America or the militant “in the cave” who sacrificed everything for his beliefs? “One thing about Awlaki no one can deny,” he said, “this man is fearless.”

That Awlaki carries weight with conservative Muslims underscores both the rivalry and proximity between militant and nonmilitant Salafis. Qadhi and Awlaki have parallel pasts: they were both born in the United States, spent part of their youth in the Middle East and entered the American Salafi movement just as it was on the rise. Awlaki later spent time in a Yemeni prison and emerged in 2008 calling for Muslims to fight the West. Recordings of his sermons continued to be sold at AlMaghrib seminars even after the students were ordered to stop in November 2009, following the Fort Hood shootings that Awlaki praised. Many of the students had grown up listening to him preach on his CDs. They trusted him then, one told me, why not trust him now?

For the tiny fraction of AlMaghrib’s students who have turned to violence, many are what Qadhi refers to as “sympathizers” of militant anger. These young, politically attuned Muslims are taken with events that don’t even register with most Americans, like two recent terrorism cases in New York that drew overflow crowds, Qadhi’s students among them. “If any Muslim is oppressed anywhere, the prevailing wisdom is that we should be standing up to help them — if we’re true believers,” says Ify Okoye, an AlMaghrib volunteer from Beltsville, Md. Sometimes, she added, “you feel guilty for living here.”

Many of today’s young American Muslims are the children of educated, successful immigrants whose passage to the United States came smoothly, in contrast to Europe’s largely working-class Muslims. For years, this bolstered the theory that American Muslim youth had been spared the alienation that fostered militancy in Europe.

But alienation has many faces. America’s youngest Muslims have grown up in a newly hostile country, with mounting opposition to the construction of mosques, a national movement seeking to ban courts from consulting shariah, or Islamic law, and rising hate crimes against Muslims. While some young Muslims have sought distance, abandoning Islam and even changing their names, others have experienced a spiritual awakening. The most conservative have found a home in Salafiya.

Salafis take their name from the Arabic word “salaf,” meaning “ancestor.” Their movement seeks to reclaim Islam’s lost glory by purging the faith of modern influences. Salafis model their lives after the first Muslims, beginning with the Prophet Muhammad, the seventh-century Meccan merchant to whom the Koran, it is believed, was revealed. They encourage a direct relationship with God through a literal reading of Islam’s primary sources — the Koran and the Sunnah, the prophet’s sayings and deeds.

Within the faith, Salafis have a reputation for intolerance and divisiveness. Like other religious conservatives, they tend to be adamant in their strict interpretations, shunning those who disagree. They denounce the veneration of saints, common among some Sufi sects. Many Salafi men insist on a fist-length beard and wear their trousers above the ankle in a desire to emulate the prophet.

While versions of Salafiya have persisted through history, its current iteration derives largely from the puritanical, 18th-century school of Saudi Islam known as Wahhabism. Today’s Salafis share the same basic theology but differ on how to manifest it. Many are apolitical, while another subset engages in politics as a nonviolent means to an end — namely, an Islamic theocracy. A third fringe group is devoted to militant jihad as the only path to Islamic rule and, ultimately, heaven. All three strains have surfaced in the West, where the movement has flourished among the children of immigrants. “It’s about this deep desire for certainty,” Bernard Haykel, a leading Salafi expert at Princeton University, says. “They are responding to a kind of disenchantment with the modern world.”

One balmy afternoon last spring, Qadhi walked across Yale’s campus, stepping around a throng of teenagers he dismissed, irascibly, as “the prefreshie tour.” He stopped before the tomblike building that houses the elite Skull and Bones society. Qadhi stared up at the brownstone facade, as if imagining the secrets it held. “You’re set for life,” he said, squinting through his sunglasses. “You get to thinking that everyone in the White House was a part of this, and it’s easy to see why people think there is a conspiracy.” After a pause, he added, “I don’t believe those theories.”

Qadhi is hardly disenchanted by the trappings of Western life. He has more than 10,000 fans on Facebook, hundreds of sermons on YouTube and a growing Twitter following. He drives a black, leather-interior Honda CR-V, often pulling into a Popeye’s drive-through for popcorn shrimp and gravy-slathered biscuits. He is planning a trip to Disney World with his wife, Rumana, and their four children.

(PSome of Qadhi’s followers find his ease with American culture perplexing, even suspicious. Yet it is his unapologetic comfort with America — his assertion that Muslims belong here as much as anyone — that has also made him a point of pride for many young Salafis. “We need to make sure that our children can live freely, and we’re going to fight for that freedom,” he told me one afternoon. “And every time I use that word, I need to make a disclaimer — I don’t mean ‘fight’ in the Tea Party sense of overthrowing the government.”

A stout five-foot-five, Qadhi chuckles easily and speaks rapidly, his hands punctuating his words with slicing motions. He is confident to a fault, often trailing a sentence with “God protect me from arrogance.” In class, he can be staid and professorial, with flashes of frivolity. He once implored students to “make love, not jihad.” He blends religious piety with entrepreneurial savvy. More than 20,000 people have signed up for “Like a Garment,” Qadhi’s new online seminar about sex in Islamic marriage. “I give explicit detail on how a man should give his wife an orgasm in a permissible manner,” he explained.

Qadhi’s platform is the AlMaghrib Institute, where he serves as academic dean. Founded in 2002 by Muhammad Alshareef, a Canadian cleric then living in Alexandria, Va., AlMaghrib is now an international enterprise, offering seminars in the United States, Canada and Britain. It reported nearly $1.2 million in revenue in 2009 and aspires to become a full-time Islamic seminary, albeit with an air of corporate America. During a recent retreat in the mountains of Ontario, AlMaghrib’s clerics whizzed along snowy bluffs on sleds drawn by Siberian huskies. “As long as you don’t touch them, it’s all right,” Qadhi said, referring to his interpretation of Islam’s ruling on dogs.

Last June, Qadhi and his family left New Haven for the outskirts of Memphis, settling into a spacious new ranch house in a well-tended subdivision. Still at work on his doctoral thesis, Qadhi found a job teaching Islamic studies at Rhodes College, which is affiliated with the Presbyterian Church.

It is something of a curiosity that Qadhi, who was raised in Saudi Arabia, Islam’s birthplace, now lives in a landscape marked by church steeples and “What would Jesus do?” bumper stickers. But the American South seems to agree with Qadhi, who often preaches on the Islamic principle of polite conduct. He takes to the gentility of his students at Rhodes, who call him sir. There is no better place to be Muslim than in America, he says, because as a minority “you feel your faith.” At times, he seems oddly Pollyanna-ish about his future in Tennessee, where someone tried to torch the site of a planned mosque last year. Qadhi concedes that living someplace like Saudi Arabia might be easier, but “it’s not my land at the end of the day,” he said. “I am an American. What else can I say?”

In Qadhi’s current incarnation, it is hard to make out the preacher he refers to as “the old me.” That Qadhi lives on via YouTube. In a television show recorded in Egypt in 2001, Qadhi, then 26, explains that one form of kufr, or disbelief, is adhering to man-made laws over God’s law. “Can you believe it?” he says. “A group of people coming together and voting — and the majority vote will then be the law of the land. What gives you the right to prohibit something or allow something?”

His young students nod their heads. “Islam is a complete way of life, a complete submission to Allah and to the rulings of Allah,” Qadhi said on the show. “It is a complete package.”

Long before Salafiya came to the United States, Qadhi’s father arrived in Houston from Karachi, Pakistan. It was 1963, and the young bachelor, Mazhar Kazi, enrolled at the University of Houston with his sights on a medical degree. One of the first foreign-born Muslims to settle in the area, Kazi took a job as a busboy and tended to his studies. He eventually married a microbiologist from Karachi and founded the area’s first mosque.

Their son, Yasir, was born in 1975, the second of two boys. When Yasir was 5, the Kazis moved to Jedda, Saudi Arabia, intent on exposing their sons to Islam and Arabic. Kazi took a job teaching medicine at the King Abdulaziz University. The family spent summers in Houston, but the boys were mostly shaped by life in Jedda, a blend of British expat culture and strict Saudi norms. Qadhi (who later changed the spelling of his surname to reflect the correct pronunciation) was precociously bookish. On weekends, he searched the local library for Tolstoy and Hemingway. By 15, Qadhi had memorized the Koran and graduated from high school, two years early, as valedictorian. Following his father’s wishes, he enrolled at the University of Houston in 1991, majoring in chemical engineering.

Qadhi had never attended a class with women and was shocked by campus life. He took refuge in the Muslim Students Association, a close-knit group of mostly Arab and South Asian immigrants. He was soon leading study circles and delivering effusive Friday sermons.

His introduction to Salafiya came in his sophomore year, when a Muslim convert from Colorado visited campus. A tall, regal man with a wispy white beard, the preacher displayed a command of Islam that Qadhi had never seen. When asked a question, he closed his eyes and recited a litany of evidence from the Koran and the Sunnah. This approach, a cornerstone of Salafiya, appealed to Qadhi’s empiricism. “It’s so disciplined and academic,” he said. Then 17, Qadhi began driving through the night to attend Salafi camping retreats, where legendary clerics lectured from Jordan and Saudi Arabia via teleconference. He drilled into Salafiya with a discipline that defied his adolescence. At a retreat in Boulder, Colo., some of Qadhi’s friends skipped out to go fishing. When they returned, Qadhi refused to share his notes. “It was very clear that this guy was going to become something and we weren’t,” said one of the friends, Amad Shaikh.

At another retreat, Qadhi fell under the sway of Ali al-Timimi. A cancer researcher from Maryland, Timimi had studied Islam in Saudi Arabia and helped spread the American Salafi movement, which began in the early 1980s as a patchwork of nonprofit groups subsidized by the Saudi government. Through shipments of free Korans and other texts, Salafi doctrine developed a strong presence at American mosques, prisons and Islamic schools. By the 1990s, the Salafi community numbered in the low thousands.

American Salafiya mirrored the movement abroad. It was largely apolitical until the first gulf war, when the United States set up a base in Saudi Arabia. The presence of American troops on Saudi soil, home to Islam’s holiest sites, was a defining moment for Salafis, giving rise to a political awakening and fueling bin Laden’s militancy. In America, some Salafi clerics began calling for political action against the Saudi regime, while others remained loyal. Qadhi was torn.

But on other matters, he steered his fellow students in Houston toward a strict code. They instituted sex segregation, policing each other for signs of deviation. When a Pakistani student organization sponsored a rock concert, Qadhi and his friends distributed fliers warning the crowds that Islam prohibited music. They did not see themselves as stakeholders in America, Shaikh recalled. Their goal was to spread Islam and then migrate to Muslim lands. “It was almost cultish,” Shaikh said.

For all his stridency, Qadhi broke one significant rule: he fell in love outside the bounds of arranged marriage. The young woman, Rumana, was a quiet, graceful college student of Indian descent. But Qadhi’s parents had their sights on other marriage candidates, and the courtship faded.

During college, jihad loomed in the backdrop of Qadhi’s life. Like many of his peers, he was taken by the legend of the American Muslims who had fought with the Afghan mujahedeen against the Soviets. Back then, talk of jihad carried little taboo, given the United States’ role in financing the resistance. Qadhi knew several men who later fought in Bosnia. Noble as it seemed, he said, “I thought there were more productive ways for me to spend my life.”

He had long thought of becoming a Muslim scholar. Shortly before graduating, Qadhi applied to the Islamic University of Medina, a leading Salafi institution. After enrolling in the fall of 1996, he called Rumana. “I can’t live without you,” he told her. “Are you willing to live a difficult life?”

Qadhi and his new wife settled into a spare apartment, and he plunged into round-the-clock study. Life in Medina deepened his faith while narrowing his tolerance for the outside world. He came to identify with political Salafiya, denouncing secular democracies and declaring Sufis and Shia “heretics.” He took up the Palestinian cause — a pathway, he said, to the anti-Semitic rhetoric that ran rampant in his circles.

In the summer of 2001, Qadhi traveled to London to teach at an Islamic conference. At the end of a class, he went into a diatribe arguing that Israel did not rightfully belong to the Jewish people. “Hitler never intended to mass-destroy the Jews,” Qadhi said, telling the audience to read a book about “the hoax” of the Holocaust. He went on to say that most Islamic-studies professors in the United States are Jews who “want to destroy us.”

Looking back, Qadhi said he fell down a slippery slope where criticism of Israel gave way to attacks on Jews. Beneath the vitriol, he said, was a sense of victimization — that non-Muslims were to blame for the afflictions of the Muslim world. “When you’re young and naïve, it’s easier to fall prey to such things,” said Qadhi, who publicly recanted years later. Last August, he joined a delegation of American imams and rabbis on a visit to the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps, which he said left him “sick” and more embarrassed by his Hitler remarks.

“It was a pre-9/11 world,” he said. “The circumstances did not dictate that we think critically.”

Two months after the London episode, Qadhi was walking to his mosque in Medina when a friend came running. “Yasir, Yasir, did you hear what happened?” the young man called out. Qadhi rushed to a neighbor’s apartment in search of a television, just as the second tower collapsed.

In the aftermath of 9/11, the American Salafi movement fell apart. As federal agents raided Muslim mosques, charities and businesses, the most prominent Salafis vanished from clerical life or landed in prison. Some of the movement’s key figures were convicted on charges unrelated to terrorism, ranging from tax evasion to visa-immigration violations. “All of these people were jailed for different things, but if you look at them collectively, you see the Salafi movement,” Idris Palmer, a onetime Salafi activist, told me.

Law-enforcement officials say that there was no policy singling out Salafis. They were rushing to root out a new enemy, with little time to grasp the theological differences separating nonviolent fundamentalists from the creed of the hijackers. Many agents did not even know what a Salafi was “and still don’t,” says Christopher Heffelfinger, a security analyst who consults with the government. Northern Virginia — then a nexus of the American Salafi movement given its proximity to the Saudi Embassy — became a focal point. Anwar al-Awlaki was still preaching in Virginia when federal agents raided 15 local Islamic offices and homes. “It’s a war against Muslims and Islam,” Awlaki bellowed in an audio address. “It’s happening right here in America.”

The most high-profile Virginia case involved Qadhi’s onetime mentor, Ali al-Timimi, who regularly preached at a Falls Church mosque. At a dinner five days after 9/11, Timimi and some of the mosque’s young congregants discussed how to respond. Prosecutors later accused Timimi of spurring the men to wage jihad against American troops overseas, saying they practiced shooting at a paintball facility. At issue in the case against Timimi were his words: his lawyers argued that he recommended that the men move to Muslim countries, while prosecutors said he was inciting jihad. They highlighted comments by Timimi unrelated to the dinner, including politically charged speeches and a statement in which he celebrated the Columbia Shuttle disaster. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

From Medina, Qadhi followed the case closely. For American clerics, he said, the message was clear: those who engage in controversial rhetoric are treading on thin ice. While 9/11 had shaken Qadhi’s movement, it also unsettled him personally. “No matter how strange this sounds, after having lived in Saudi Arabia for so long and also in America for so long, I could fully understand the fear, the anger, the frustration, the paranoia on both sides,” Qadhi says. “I could understand ‘they’ and ‘us.’ ”

Qadhi began to wrestle with some of his own beliefs. It troubled him that Salafiya, even in its nonmilitant form, had helped shape the ideology of groups like Al Qaeda. “What type of Islam are we going to teach people?” he recalled thinking. “This isolationist Islam? This Islam of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ — is that healthy? Is that what my religion is?”

At the time, Qadhi was on track to become Medina’s first American doctoral candidate. He wondered if he had a more promising future in America, where the Salafi movement, bereft of leaders, was in crisis. From Houston, Qadhi’s father — who had retired and was volunteering as a prison chaplain — encouraged his son to leave Saudi Arabia, which he believed had left Qadhi “totally brainwashed.”

“I said, ‘Come back to America; this is your land,’ ” Kazi said in an interview at his home, sitting in what he called his “Archie Bunker chair.”

In 2004, Qadhi applied to Yale. Some of his contemporaries saw the move as strategic. “It was a stepping stone,” Imam Abdullah T. Antepli, the Muslim chaplain at Duke University, told me. “He knew that with that Yale ticket, people would take him more seriously.”

Qadhi’s Saudi professors were aghast that he would switch to a Western university to study Islam. Yale’s professors were also surprised. The religious-studies department had never taken on a graduate of the Saudi educational system. “You admit someone from Saudi Arabia, you don’t know how much intolerance you let into an American university,” says Frank Griffel, a professor of Islamic studies.

But Qadhi impressed Griffel as “profoundly intelligent” and willing to engage in critical thinking. At Medina, Qadhi’s studies revolved around the search for an absolute religious truth. At Yale, the line of inquiry was markedly different. In Qadhi’s first class with Griffel in the fall of 2005, the subject was a 12th-century Sufi jurist. “You, Yasir, probably know more about this guy,” Griffel said. “But we’re going to study how to study him.” Qadhi was struck by this analytical approach. “The question is more historical in nature — it’s about where did this idea come from, how did it affect later ideas,” Qadhi said.

For Qadhi, the Koran remained the unequivocal word of God. But he began to think more critically about the “man-made” canon that informed Islamic theology. So much of Qadhi’s intransigence — especially toward other Muslim sects — was based on the view that his tradition was divinely ordained. He came to see Salafiya as yet another “human development” that was handed down over generations and therefore subject to imperfection. “I realized that, in many issues, only God knows the ultimate truth,” he says.

Qadhi landed on the American preaching circuit with force, and his following skyrocketed among young Salafis. America’s leading clerics were converts who had risen to prominence because they could translate an intricate theology into an American vernacular. Qadhi did the same but as the proud son of Muslim immigrants. Plus he was a Salafi — or so it seemed.

In July 2006, at a conference in Copenhagen, Qadhi did the unthinkable: he shook a woman’s hand in a spontaneous challenge to her perception of fundamentalists, he said. The woman, Mona Eltahawy, a columnist on Arab and Muslim issues, wrote about the exchange, which became known in Salafi circles as the “when-Yasir-met-Mona moment.” The handshake drew a death threat from a man in London.

The following year, Qadhi further pushed the limits, making a pact of “mutual respect and cooperation” with American clerics of the Sufi order, Salafiya’s longtime enemy. Several of Qadhi’s former Saudi professors publicly assailed him, a signal he had become too prominent for them to ignore. Qadhi began to step away from the Salafi label, rebranding his movement “orthodox with a capital O.” While he remained devoted to Salafiya’s core tenets, his followers struggled to keep pace with his changes. Others remained skeptical. “Is he being instrumental and opportunistic, or has he really abandoned some of these Salafi beliefs?” said Haykel, the Princeton professor. “He’s engaged in an incredible performance of reinvention that I’m not sure he’ll be able to pull off.” The same question hovered over Qadhi’s institute, whose founder, Alshareef, once gave a sermon titled “Why the Jews Were Cursed.”

Meanwhile, as Qadhi honed a new message, he was roundly dismissed on jihadist forums as a “sellout.” One detractor was Samir Khan, a young blogger from North Carolina who eventually moved to Yemen and now runs the Al Qaeda magazine, Inspire, according to law-enforcement officials.

While Khan was still living in the United States in 2007, he wrote several blog posts about Qadhi. “He has done good, and we do not deny this,” read one. But Qadhi’s “wrongdoings,” he continued, “can destroy the Muslims.”

Suspicion surrounded Qadhi. In February 2006, he was crossing from Canada into the United States when American border agents pulled aside his van and ushered his family into a room. An agent told Qadhi he was “waiting for permission from Washington” to let Qadhi back into the country, he recalled. They were freed more than five hours later.

It was the first sign that Qadhi was on the terrorist watch list. From then on, he and his family traveled separately. “I’m not going to be humiliated in front of my kids,” he said. At airports, he became accustomed to long interviews with border agents, who downloaded his laptop hard drive and searched his cellphone. They photocopied notes he kept on his sermons and even asked for his definition of jihad. F.B.I. agents in New Haven questioned him about two American acquaintances who had been charged with terrorism-related offenses. Qadhi said he knew nothing of their activities, but the agents pressed him to report on anyone who expressed views that “might be of interest,” he recalled. He refused, saying, “This is America, not Soviet Russia or East Germany.”

Increasingly, Qadhi felt backed into a corner. In August 2006, at a meeting for Muslim leaders in Houston, he walked up to Daniel W. Sutherland, a Homeland Security official. “Hi, I’m a pacifist Salafi,” Qadhi said to him. Looking stunned, Sutherland sat and talked with Qadhi for more than an hour.

Then in May 2008, Qadhi received an invitation from Quintan Wiktorowicz, an analyst for a government agency that was hosting a conference on counterradicalization. (Wiktorowicz was recently named a senior director at the National Security Council.) In attendance were British and American intelligence officials, including the director of Homeland Security at the time, Michael Chertoff.

During a break, Qadhi spotted a Houston acquaintance who happened to work for Chertoff. “I said, ‘Don’t you think it’s ironic that on the one hand, you’re reaching out for my expertise and wanting my help, and on the other hand, you’re harassing and intimidating me as if I’m a potential terrorist?’ ”

In the West, jihad is often depicted as a self-contained, violent cause. But in Qadhi’s world, it exists within a panoply of complex and overlapping issues. The most immediate question is not whether to fight overseas but how to make peace living in the pluralistic West.

Debates pivot on arcane theological points from the ninth century, a time when religious empires reigned, not secular nations. Classical scholars reference a world divided between dar al-Islam, the land of Islam, and dar al-harb, the land of war. But which land is America?

“If we’re not at war, why is America killing Muslims throughout the world?” says Basil Gohar, 30, who has studied with Qadhi. “If we are at war, how can we live in America peacefully?”

Even absent the question of war, Western Salafis ponder their loyalties. Internet forums buzz with talk about the concept of al-walaa wal-baraa, which is rooted in Koranic verses dictating allegiance to Muslims over non-Muslims. Qadhi’s students are divided over whether to vote, pay taxes that support the military or even celebrate Thanksgiving. “These sorts of things, they are the fault lines,” says Okoye, the student from Maryland.

Qadhi sees in his students an earlier version of himself — the passionate Salafi who took comfort in a black-and-white world. He prods them to think “in colors” and find a balance between loyalty to Islam and to America. He urges them to pay taxes and vote, drawing the line at military service, given Iraq and Afghanistan. “There is no draft,” he said. “Thank God for that.”

For Qadhi and his students, nothing tested those loyalties more than the events after the underwear-bomb plot of December 2009. Whenever a terrorism suspect is identified, AlMaghrib runs the name through its database of alumni to see if there is a match. “Oh, my God,” Qadhi said when a colleague told him that the 23-year-old suspect, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, had been his student.

Qadhi searched his memory. The son of a prominent banker, Abdulmutallab had been living and studying in London. He had taken two AlMaghrib classes before attending the institute’s 16-day Houston conference in 2008. There, Abdulmutallab kept mostly to himself. “He never got into political issues,” says Abdul-Malik Ryan, 36, a lawyer from Chicago who studied with him every morning.

As media outlets discovered the connection, AlMaghrib’s leaders rushed to contain a crisis. The institute’s vice president, Waleed Basyouni, reached out to the F.B.I.’s Houston field office. Agents wanted to interview all 156 students who attended the 2008 conference. “I said, ‘If you start going to our students and terrifying them, and they stop coming, we will close down,’ ” he recalled telling the agents. “ ‘You would be pushing the students to go to basements, small circles, on the Internet. So it’s in your benefit that this organization stay open.’ ”

In previous cases, F.B.I. agents dropped by the homes of some AlMaghrib students, unannounced. This time, they issued a subpoena but agreed to arrange interviews in advance and to send female agents to question the women. The clerics urged the students to cooperate, but many balked, prompting Qadhi’s 50-minute conference call from Yale.

Veering between high-pitched emotion and tedious scholarship, Qadhi argued that the case presented no conflict of loyalties because Abdulmutallab, by all appearances, committed a crime, violating both American and Islamic law.

But, one student asked, what about America’s transgressions? Why was Qadhi focused on the militants? He responded that he had bluntly criticized American policies to State Department and other officials, telling them “the root cause of this terrorism is terrorism perpetrated at the state level.”

Even so, Qadhi urged his students to “chill out” and use common sense. “You need to look at the repercussions of what you are going to do to yourself, to your family, to your society and to the Muslims that are around you,” he said.

The students cooperated, and in subsequent meetings with the F.B.I., an agent told Qadhi and Basyouni that the bureau did not consider AlMaghrib a terrorist threat, said the clerics. (An F.B.I. spokesman declined to comment about Qadhi or the investigation.)

The Abdulmutallab episode drew a new line in the long-distance battle between Qadhi and Awlaki. The Yemeni-American cleric announced that Abdulmutallab’s operation was in retaliation for American “cruise missiles and cluster bombs.” By then, the United States had authorized the assassination of Awlaki, provoking outrage among many of Qadhi’s students.

Qadhi seemed to be riding a pendulum of self-preservation. If he lurched too far toward appeasing the government, he risked losing his base.

That March, Qadhi rose before a crowd of thousands in Elizabeth, N.J., to finally speak about Awlaki. “I am against this preacher when he tells our youth to become militant against this country while being citizens to this country,” Qadhi told the packed auditorium.

“But when my government comes and says, ‘We’re allowed to take him out; we’re allowed to kill him; we’re allowed to assassinate him,’ I also put my foot down, and I say to my own government, ‘Shame on you!’ ” The audience listened raptly. “Be angry every time a bomb is dropped on innocent civilians in the name of the war on terror,” Qadhi bellowed. “Be angry every time our tax dollars are spent to oppress yet another group of innocent Palestinians. Be angry every time more draconian measures are utilized against us in this greatest democracy on earth.”

Never before had Qadhi so forcefully condemned America’s policies in public. But “channel that anger,” he continued, “in a productive manner.” He urged a “jihad of the tongue, a jihad of the pen, a jihad that is not a military jihad.”

American Muslims, Qadhi told the audience, needed to abide by the laws of their country, understanding that had they been born in Palestine or Iraq, their “responsibilities would be different.” He did not elaborate.

It is this kind of ambiguity that gnaws at some of Qadhi’s students. “We just get wishy-washy nonanswers,” one female student told me, adding that Qadhi’s “jihad of the tongue” was unconvincing. Being martyred in the battlefield, she said, is “romantic,” while “lobbying your congressman is not.”

The call to prayer soars through the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Houston, its lobby adorned with a fresco of the Texan flag. Every summer, AlMaghrib’s most-devoted students convene here for a two-week Ilm Summit, transforming the ballroom floor — a corporate tableaux of overstuffed sofas and dim lighting — into a version of Islamic utopia.

“Ilm,” in Arabic, means “knowledge.” From dawn to night, the students immerse themselves in advanced Islamic theology and Koran recitation under the guidance of Qadhi and other clerics. The men favor long tunics, and some women wear niqabs, the full-face veil. Most are upper-middle-class college students of South Asian descent who pay $1,500 to attend. To the hotel’s Hispanic waiters, they seem otherworldly. The men and women eat, study and even ride the elevators separately.

Yet the so-called AlMaghribis upend easy stereotypes. The women are a forceful presence in class and can be spotted on breaks engaging in fierce arm-wrestling matches. The most dominant trait among the men is a quintessentially American geekiness. Qadhi, like many of his students, is a “Star Trek” fan. His lectures are laid out on PowerPoint as students crouch over laptops. Between classes, talk often turns to the latest AlMaghribi courtship.

The mood darkened last July after Qadhi announced that agents from the local F.B.I. office would be dropping by for a “roundtable discussion.” The ballroom fell to a hush as Qadhi and Basyouni led Brad Deardorff, supervisory special agent of the Houston division, to the stage. He smiled tentatively as Qadhi began a quick speech about the need to counteract extremism. Deardorff talked about the history of militant movements, saying there was “no standard profile for an Islamist terrorist.”

Then came the students’ questions, submitted in writing. “How do you expect us to help you” read one question, “when there are F.B.I. informants in our mosques?”

“Jeez, that’s a tough question,” Deardorff said. “We don’t target mosques. We do collect domestic intelligence. But mosques are buildings. Mosques don’t conspire. Mosques don’t blow things up.”

The students stared at him incredulously. It struck some as ironic that Qadhi would engage in a public discussion with the F.B.I. about “terrorism” — which they deemed a loaded word — when the underlying theological issues remained off limits. In a poll last year on Qadhi’s blog, Muslim Matters, participants ranked “jihad” as the No. 1 subject in which they wanted academic instruction.

There are several kinds of jihad, which is translated to mean “striving in the path of God.” While progressive Muslims emphasize the spiritual form, Qadhi and other conservatives say that the majority of the Koran’s references to jihad are to military struggle. Qadhi’s interpretation makes him neither a hardline militant nor a pure pacifist. While he unequivocally denounces violence against civilians, he believes Muslims have the right to defend themselves from attack. But he says “offensive jihad”— the spread of the Islamic state by force — is permissible only when ordered by a legitimate caliph, or global Muslim ruler, which is nonexistent in today’s world.

Such fine distinctions were less pronounced before 9/11, when Qadhi and others preached openly about the glory of Islam’s early military triumphs. In a decade-old sermon about one of Islam’s landmark battles, Qadhi said, “once a prophet has become ready for jihad, for fighting, then he will not take off his armor until he has actually met the enemy.”

By the time he returned to the United States in 2005, AlMaghrib had canceled a popular class on Islam’s military history, and its instructors largely avoided current events. Some students inferred from Qadhi’s silence a tacit support for militant groups. “Everyone was always like: ‘We know he believes it. He can’t say it publicly,’ ” recalled Lauren Morgan, who is 26 and a former student of Qadhi’s. She said she and other students had openly sympathized with militants. “I think if you’re going down the Salafi interstate, the jihadi exit is open for you,” Morgan said. “It’s there.”

Many students first heard Qadhi denounce jihadist movements almost a year after the London bombings. That same month, June 2006, AlMaghrib released a statement calling terrorism “a perversion of the true Islamic teachings.”

The central contest between Qadhi and militants like Awlaki hinges on a rather abstruse point: how to define America in Islamic terms. Qadhi likens his country to Abyssinia, the seventh-century African kingdom that gave refuge to the prophet’s followers. In exchange for upholding the laws of the land, they were allowed to worship freely — a contract Qadhi equates to an American passport or visa. Breaking the contract by joining militant groups at war with America constitutes treachery, Qadhi says, which is forbidden in Islam. Awlaki, by contrast, compares America with ancient Mecca, where the prophet’s followers were persecuted, forcing them to flee and later fight back.

Critics take issue with the technical nature of the debate. Qadhi’s students, they argue, could conclude that joining a militant group is permissible provided they renounce their citizenship. This is further complicated by his refusal to address whether the Islamist uprisings in Iraq and Afghanistan constitute legitimate jihads.

Saying yes would open the door to public recriminations, but denying the legitimacy of those insurgencies would fly in the face of Islamic law, says Andrew F. March, a professor at Yale who specializes in Islamic law. “The conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine are unambiguous examples of jihad or war against an outside invader,” March says. “There is no mainstream juridical opinion that says that Muslims cannot resist that.”

Under mounting pressure from students, Qadhi and another AlMaghrib scholar, Abu Eesa Niamatullah, considered teaching a course on the fiqh, or jurisprudence, of jihad. “What stopped us?” Niamatullah says. “Picture two bearded guys talking about the fiqh of jihad. We would be dead. We would be absolutely finished.”

On Oct. 18, Qadhi posted a 5,000-word essay on his blog, trying to jump-start a discussion on jihad. He argued that extremists cherry-pick verses from the Koran to justify actions antithetical to the faith, while United States policy also plays a central role in radicalizing Muslim youth. What Abdulmutallab did not hear at AlMaghrib, Qadhi lamented, “was a discourse regarding the current political and social ills that he felt so passionately about, and a frank dialogue about the Islamic method for correcting such ills.”

“It is an awkward position to be in,” he wrote of his situation. “How can one simultaneously fight against a powerful government, a pervasive and sensationalist-prone media and a group of overzealous, rash youth who are already predisposed to reject your message, because they view you as being a part of the establishment (while, ironically, the ‘establishment’ never ceases to view you as part of the radicals)?”

One week later, Qadhi was flying through Dallas. He had traveled free of hassle for nine months and seemed to be off the watch list. But now, border agents were stopping him. They wanted to ask a few questions. “Here we go again,” he said.

Qadhi’s ambiguous relationship with the government reflects a quandary facing the Obama administration: whether to engage with Muslims across the ideological spectrum. While many American Muslim leaders have been hit by accusations of extremism, Qadhi is a natural target. Self-described terrorism watchdogs refer to AlMaghrib as “Jihad U.,” and last year, a Fox News reporter called Qadhi a “wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

While Qadhi hardly seems the caricature of his critics’ rendering — the stealth Islamist plotting a shariah takeover of the White House — his views reflect a vision that many Americans would find objectionable. He hopes that the world will someday fully adhere to his faith, he said, conceding that it would most likely be “not in my lifetime.” Egypt’s recent uprising, he wrote on his blog, illustrates that change cannot come from militancy but “begins in the heart and in the home, and it shall eventually reach the streets and shake the foundations of government.”

As the administration confronts domestic radicalization, some government analysts say they have much to learn from clerics like Qadhi. “We’re trying to get our arms around how to engage with Yasir and people like him,” a senior counterterrorism official told me. “It’s a new issue.” One concern, officials told me, is their uncertainty about how world events might harden the thinking of clerics like Qadhi.

In the search for answers, the Obama administration has studied counterradicalization approaches overseas. In Europe, some policy makers argue that nonmilitant fundamentalists are the problem, not the solution, because their rigid interpretation of Islam fuels the very radicalization they profess to fight. The British government was rebuked for providing funds to nonmilitant Salafi organizations.

The U.S. Constitution would prevent such financing. But the question remains to what extent the administration will consult with nonviolent fundamentalists or help them by creating what Qadhi and others call “a safe space” in which Muslims are free to discuss controversial issues without the fear of repercussions.

“There is a way to stop extremism,” he claimed, “but it’s not palatable for Americans.”

Qadhi recently went live with a Web site devoted to issues of jihad. He is calling it The J Word.

Other American clerics have also begun to speak out, most notably Imam Zaid Shakir, who posted a widely read letter online aimed at dissuading the “would-be mujahid,” or warrior.

Gone are the days when Qadhi would dismiss teaming up with clerics of different schools. There were too few Salafis left in America. “I need help,” Qadhi told me one afternoon last month.

He was sitting in the library of his new home, where more than 10,000 books line the cherry-stained shelves. Memphis is a long way from the centers of Islamic thought — places like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. It would be folly, Qadhi said, to think that a young American cleric could solve the theological puzzles that have invited centuries of debate.

But he was certain of one thing: only America’s clerics could lead the way forward for their young flocks.

“American Muslims are at the forefront in battling Islamic extremism because they have everything to lose if anything else happens,” Qadhi said. “They’ll lose their American identity, and they’ll lose their prestige, whatever prestige remains of our religion that we would like to have in this land.”

- © 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Magazine of Sunday, March 20, 2011.