| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted July 13, 2003 |

|

|

By BARRY BEARAK |

LATE one afternoon, during the long melancholia of the hungry months, there was a burst of joyous delirium in Mkulumimba. Children began shouting the word ngumbi, announcing that winged termites were fluttering through the fields. These were not the bigger species of the insect, which can be fried in oil and sold as a delicacy for a good price. Instead, these were the smaller ones, far more wing than torso, which are eaten right away. Suddenly, most everyone was giddily chasing about; villagers were catching ngumbi with their fingers and tossing them onto their tongues, grateful for the unexpected gift of food afloat in the air. Adilesi Faisoni was able to share in that happiness but not in the cavorting. For several years, old age had been catching up with her, until it had finally pulled even and then ahead. Her walk was unsteady now, her posture stooped, her eyesight dimmed. As the others ran about, she remained seated on the wet ground near the doorstep of her mud-brick hovel. It was the same place I always found her during my weeks in the villages of Malawi, weeks when I was examining the mechanisms of famine. ''There is no way to get used to hunger,'' Adilesi told me once. ''All the time something is moving in your stomach. You feel the emptiness. You feel your intestines moving. They are too empty, and they are searching for something to fill up on.''

Hunger was the main topic of our talks. Most every year, Malawi suffers a food shortage during the so-called hungry months, December through March, the single growing season in a predominantly rural nation. Corn is this country's mainstay, what people mainly grow and what people mainly eat, usually as nsima, a thick porridge. Ideally, the yield from one harvest lasts until the next. But even in good times the food supply is nearing its end while the next crop is still rising from the ground. Families often endure this hungry period on a single meal a day, sometimes nothing more than a foraged handful of greens. Last year's food crisis was the worst in living memory. Hundreds, and probably thousands, of Malawians succumbed to the scythe of a hunger-related death.

| Why People Still Starve |

|

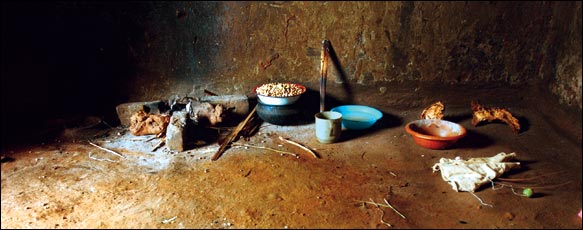

Marco Longari/Galbe.com, for The New York Times |

| The wordily goods of Adilesi Faisoni, who lives in this room with a daughter and 10 grandchildren. |

Among those who perished were Adilesi's husband, Robert Mkulumimba, and their grown daughter Mdati Robert, herself the mother of four young sons. The two died within a month of each other, unable to subsist on the pumpkin leaves and wild vegetables that had become the family's only nourishment. ''The first symptom was the swollen feet, and then the swelling started to move up his body,'' Adilesi said of her husband's illness.

It was strange the way Robert seemed to fade. Before the start of the hungry months, it had been he who had kept the family going, leaving before dawn each day to sell firewood or tend someone's fields. But then work became impossibly scarce, and Robert seemed to be using himself up in the search for it. ''At the peak of the crisis, there was nothing to do but beg, and you were begging from others who needed to beg.''

As most people visualize it, famine is a doleful spectacle, the aftershock of some calamity that has left thousands of the starving flocked together, emergency food kept from their mouths by the perils of war or the callousness of despots or the impassibility of washed-away roads. But more often, in the nether regions of the developing world, famine is both less obvious and more complicated. Even small jolts to the regular food supply can jar open the trapdoor between what is normal, which is chronic malnutrition, and what is exceptional, which is outright starvation. Hunger and disease then malignly feed off each other, leaving the invisible poor to die in invisible numbers.

|

|

|

Photographs Marco Longari/Galbe.com for The New York Times |

| Three years ago, Adilesi's daughter Lufinenti, left, separated from her husband, who later died after a long illness. Adilesi, center, lost h husband, Robert, to starvation last year, and malnourished children in the Likuni mission hospital pediatric ward in Likuni, Malawi. |

Nowhere is this truer than in sub-Saharan Africa, where President Bush was recently scheduled to travel. Each year, most nations in the region grow poorer, hungrier and sicker. Their share of global trade and investment has been collapsing. Average per capita income is lower now than in the 1960's, with half the population surviving on less than 65 cents a day. It is a situation seldom noticed, as wars on poverty are neglected for wars more animate. African countries now hold the 27 lowest places on the human-development index -- a combined measure of health, literacy and income calculated by the United Nations. They occupy 38 spots in the bottom 50.

During the past decade or so, the poorest of Africa's poor have suffered as rarely before. Merely to survive, they have sold off their meager assets -- household goods and farm animals and the tin roofs of their homes. Just now, the most urgent need is in Ethiopia, Eritrea and Zimbabwe. But hunger has become a chronic problem throughout the region, often occurring even under the best of weather conditions. The World Food Program warns that nearly 40 million Africans are struggling against starvation, a ''scale of suffering'' that is ''unprecedented.'' Coincident with the hunger is H.I.V./AIDS, which has beset sub-Saharan Africa in a disproportionate way, cursing it with 29.4 million infections, nearly three-quarters of the world's caseload. Very few of the stricken can afford the drugs that forestall the virus's death work, and family after family is being purged of its breadwinning generations, leaving the very young and the very old to cope.

With survival so precarious, life is lived at the edge of nothingness, easily pushed over the side. Take Malawi, I was told again and again -- for this land-locked, overpopulated nation in southeastern Africa seems to be a favored specimen of researchers. There is a relative innocence to Malawi's impoverishment: no tyrannical dictator currently in power, no army of goons marauding in civil war, no disastrous weather wiping out the harvest. And yet last year, the nation was nudged into starvation. It happened while there was grain in the stores, if only the poor had the money to buy it. It happened while well-meaning people were arguing about whether it was happening at all.

To track the origins of the crisis, my plan was this: to find a family that had lost someone to last year's hunger and then work my way back through the hows and whys. Though I mostly shuttled over the narrow and soggy mud roads between Mkulumimba, Adilesi's village, and Lilongwe, the capital, the actual route of causality reaches beyond Malawi's borders. It extends toward wealthier nations and their shared institutions -- the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It travels the uncertain ups and downs of global commodity prices and currency valuations -- and of course passes into the limited access roads of humanity's conscience.

"The new generation are the unfortunates, because now there is a food shortage every year,'' Adilesi said. ''Things began getting bad when I was done with my childbearing years. If they had been this bad before, all my children would have died.''

In a Malawian village, guests are customarily greeted outside and offered a mat as a seat. Adilesi's front door faced a broad clearing that slanted down, allowing a splendid view of cornfields and acacias and the Dzalanyama Mountains in the distance. About 20 yards to the left was a banana tree and the ruins of an outhouse, its mud walls half-collapsed by a recent storm. The main house itself was a single room, about 9 feet by 12 feet, with a roof of bundled grass. In one corner were the ashy remnants of a small fire. Otherwise, the room was empty but for a tin pail, two pots, a few baskets and plastic bowls and some empty grain sacks that could be used as blankets. Adilesi lived in this hut with her daughter Lufinenti and 10 grandchildren. It was hard to imagine the geometry that would allow them all to sleep in so spare a space.

''We squeeze like worms,'' Adilesi said, explaining rather than complaining.

Thin-faced and withered, the old woman owned only one set of clothes, a colorful wrap that went around her waist and a faded T-shirt that showed a San Francisco street scene and advertised Levi's 501 jeans. The lettering proclaimed, ''Quality Never Goes Out of Style.'' She had no idea what the words meant. ''Is this something offensive?'' she asked in Chichewa, Malawi's main language, bending her head down so she could examine the thinned cloth. The villagers all bought such used clothing, the discards of people from richer nations. Children who had never seen television unwittingly sported apparel that allied them with Ninja Turtles and Power Rangers. Often, holes in these shirts rivaled the size of the remaining garment. This shamed the children, and some refused to go to school. ''I have no idea what San Francisco is,'' Adilesi said with a smile, repeating the words she had just been told. ''I couldn't tell you whether it's an animal or a man.''

She did not know her age, either, but she could remember the historic famine of 1949. She was a youngster then, that year when the skies cruelly withheld the rains. The undisturbed sun not only parched the cornstalks; it seemed to melt the glue that held the village together. Neighbors, once generous, hid away what food they had, afraid of theft. Women sang prayers of apology to their ancestors for any conceivable wrongdoing and begged them to reopen the clouds. Men wandered far from their homes, disappearing for weeks in a desperate search for work. ''We refer to it simply as '49,'' Adilesi said.

She married Robert soon after. She can't recall exactly when. Robert was a nephew of the village chief, and their wedding was preceded by an evening of dancing, with the entire village sharing in a feast of two goats, several chickens and homemade beer. Vows were recited at the African Abraham Church nearby. Adilesi would later bear 12 children, including 8 who lived to be adults -- an average rate of survival in a country where half the children suffer stunted growth and one in four die before age 5.

Robert, tall and stout, was a good provider. As a young man, he went to South Africa and toiled in the mines. Then, back in Malawi, he worked for the forestry department, slashing away underbrush with his panga knife. In a village of farmers, he was one of the few men who carried home monthly paychecks. But that job ended four years ago, when the government, under pressure from foreign lenders, drastically reduced its payroll. Robert then spent more time farming and doing ganyu, day labor.

Toward the end of 2001, after an overabundance of rain and a disappointing harvest, corn prices leapt as high as 40 kwacha per kilo, about 50 cents, a forbidding sum for people used to paying a tenth as much. Foraging became necessary, as it had been in '49, as it was last year, as it is even now. The toil was not unproductive. In the openness of the plain, with the daily rain slapping hard at the mud, edible leaves reached out for the taking from small stems. They held vitamin C, some iron, some beta carotene. Occasionally there were tubers. People could eat, just not a balanced diet, just not enough.

Hunger, like many diseases, is often an abettor of death rather than an absolute cause. Who really knew: was it the tuberculosis or the malnutrition that came first, and which of them delivered the fatal blow? But symptomatically, starvation usually arrives with anemia and extreme wasting and swelling from fluid in the tissue. There can be loss of appetite, and there can be diarrhea. Robert suffered all these symptoms. That a grown man would be among those to succumb to the hunger was not so uncommon. Men, it was explained to me, used up more of themselves in the unceasing search for ganyu.

Whatever the undertow, Robert grew too weak to work. He and Adilesi went to the government hospital, where he was treated for malnutrition, then later treated for malaria, then sent home. When they released him, the doctors said he needed to eat better or he would die. Inevitably, there was little food, so he began his capitulation, imparting final goodbyes. ''He told me we needed to remain united as a family,'' said Kiniel, 16, the youngest of his children.

Robert's daughter Mdati fell ill soon after he went into his decline. She was about 30. Her husband had been a philanderer to whom she had said good riddance, and now she was suddenly incapable of caring for their four sons herself. The entire family had always depended on her. Mdati was the only one who could read and write. ''She went to school up to the second grade,'' said her sister Lufinenti. ''She was very smart.''

Unlike her father, Mdati couldn't keep food down when she found something to eat. This raised a suspicion that she had somehow been bewitched.

The family regularly attended the African Abraham Church, a tiny red-brick building with pews and an altar molded out of mud. As with most Christians in the area, they found ways to blend witchcraft into their beliefs. ''Some people protect their fields with charms, but we can't afford such things,'' Adilesi told me. This safeguard against thievery required the intercession of someone with magical powers, a sing'anga. (My interpreter -- the daily intermediary between my English and the villagers' Chichewa -- used the word ''witch doctor,'' though a more respectful term would be ''traditional healer.'') The family had great hopes that a sing'anga could break the spell that gripped Mdati. They took her to two of them.

The first, Bomba Kamchewere, is a tall, bony man with a missing front tooth. When I visited him, he spread out a mat of tightly stitched reeds so we could sit together beneath his favorite tree. He had been tutored, in dreams, by Jesus himself, he said. But even with divine insight into the curative uses of roots and herbs, his powers had limits. While he claimed to cure stomachaches, venereal disease and tuberculosis, he confessed that other sicknesses baffled him. AIDS was particularly confounding, as was njala, or hunger, which had been Mdati's problem. ''With her case, the spirits told me I could not do anything,'' he said. Then, somewhat shamefully, he confessed that around that time he himself had endured njala, quite frighteningly so. ''I went three weeks without any solid food, and I developed some strange swelling.'' At a hospital, the doctors recommended that he eat more, which was advice that struck the sing'anga as less than a revelation.

Mose Chinkhombe, a young, self-confident man with a spacious smile, was the second healer. His home was hours away in the village of Chiseka. To get there, the starving Mdati, limp as a rag doll, had to be placed on a borrowed bicycle and guided over the roads by five companions, who took turns keeping both her and the wheels steady.

A year later, the healer still remembered her. ''My diagnosis was anemia,'' he said as he sat in a dark room on a half-sack of dried lime, all the while shooing flies with an oxtail. He was in his vocational attire, a spotless white frock and floppy hat. ''She was so weak from lack of food,'' the healer said. ''I could treat her for this anemia. But I told her she needed to eat enough food to recharge her body. When she left, she had improved slightly. But then I heard she died.'' He nodded rather forcefully as he said this. Then, perhaps in defense of his medical craft, he apparently felt he needed to tell me the obvious, that the ''big hunger'' had taken a great many lives during those dismal months.

There is a belief that when a stray black dog crosses your path, terrible times will come, he said. ''Last year,'' he explained, ''a black dog walked across the entire country.''

Some 11 million people live in Malawi, though far too few live especially long. Average life expectancy from birth has fallen to 36, one of the lowest figures anywhere, according to the World Health Organization. Tuberculosis cases have doubled in the past 10 years, and an estimated 16 percent of people ages 15 to 49 have H.I.V./AIDS, though with little testing going on, few of them know it. Nearly 500,000 children have lost one or both parents to the virus, according to the United Nations. In the villages, where AIDS is seldom discussed, people call it ''government disease,'' because it seems to spring from the city.

For the poor, conditions began rapidly deteriorating in the early 90's, during the last days of the ''Lion of Malawi,'' Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda, the Western-trained physician who was the nation's dictator for 40 years. Tobacco is Malawi's only major cash crop, and the doctor amassed a fortune by granting himself valuable licenses to grow it. At the same time, his government benefited from the foreign aid of prosperous friends. The West applauded his steadfast anti-Communism; South Africa admired his tolerance of apartheid. Banda ruled -- ruthlessly and myopically -- until 1994, long enough to take himself well into his 90's and senility.

By then, geopolitical necessities had changed, as had theories on how to develop the third world. Benefactors began attaching tighter strings to their money, first during the final decade of the Banda regime, then with the subsequent elected government. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund had entered their ''structural adjustment'' period. Austerity in government spending was preached, the overriding principle being that the poor were best served through the efficiency of free markets. The fine print in most loan agreements committed governments to reduce subsidies, curtail spending and sell off monopolies.

Whatever eventual benefit there might be in such reforms, the immediate impact on Malawian farmers -- paupers during the best of times -- was distress. Corn prices, no longer set by the government, became unpredictable. Given the risk caused by instability, the private sector did not mature as expected. Worse yet, the kwacha was repeatedly devalued. Falling prices in the world tobacco market had strained already thin foreign-currency reserves. At the urging of the I.M.F., the government instituted small devaluations in 1990 and 1991 and two larger ones in 1992. Finally, in 1994, Malawi moved from a fixed exchange rate for the kwacha to one that floated. For farmers, that meant the cost of fertilizer, an imported good, ballooned as the kwacha shriveled.

Before, fertilizer had been subsidized. Loans had been, too. Farmers now found themselves adrift ''in the worst of both worlds, a Bermuda Triangle,'' deprived of the benefits of a regulated economy while yet to gain the benefits of a free market, said Lawrence Rubey, the United States Agency for International Development's chief of agriculture in Malawi. He gave an example with some dismal arithmetic: in dollar terms, the price of a bag of fertilizer had actually gone down. But in devalued kwachas, the cost had risen fivefold. This was devastating to farmers with badly leached soil. ''The past arrangement of high state control of the economy was inefficient, but at least it was stable,'' Rubey said.

A yearning for the stability of the Banda days -- though rarely for the doctor himself -- is a commonly expressed sentiment throughout the nation. Malawi's youthful democracy has lacked equilibrium, even though Bakili Muluzi, a onetime Banda protege who fell out of favor, has been its only president. The unsteadiness results in large part from the pull-and-tug of two parallel sources of power, the elected government and the international patrons who finance it. Like many poor, heavily indebted countries, Malawi operates something like a business in receivership. Lenders and donors -- among them the World Bank, the I.M.F., the British, the Americans and the European Union -- carefully monitor fiscal policy and budget expenditures. Their approvals are necessary, or their generosity is withdrawn. The spigot of aid goes on, off, on, off.

Understandably, this has made for a peevish relationship. The Malawians quite correctly contend that the donors are hypocrites: while opposing state subsidies elsewhere, wealthy nations hand out $1 billion a day to their own farmers, about six times what they give in development aid to the globe's poor. (Nicholas Stern, the World Bank's chief economist, once pointed out that each day, the average European cow receives $2.50 in subsidies while 75 percent of the people in Africa are scrimping by on less than $2.) These subsidies also depress commodity prices, undercutting the ability of developing nations to compete in world markets and get their nations off the dole.

The benefactors, on the other hand, quite correctly contend that the government is persistently wasteful and inconsistently honest, prone to overspending on frivolous travel and lax in underwriting programs for the poor. So they give their aid with a chiding finger and chastening attitude: Malawi needs better government!

And yet good government, like good deeds, is most often a complicated matter.

With fertilizer so unaffordable, the government in 1998 cooperated with the British, the World Bank and others to furnish beleaguered farmers with a ''starter pack,'' enough free seed and fertilizer to grow a healthy quarter-acre, about 15 percent of a typical family plot. Soon, the cornfields of Malawi took on the look of a bad haircut, with one cluster of stalks as high as an elephant's eye and the rest barely above the knee.

The starter-pack program combined with favorable weather to produce a bumper crop in the 1998-99 season. In fact, the surplus was so great that a newly established government safeguard, the National Food Reserve Agency, was able to purchase huge amounts, fattening its grain stockpile to about 190,000 tons. For Malawi, so often hungry, this cache was a comforting buffer against famine. But it was also costly. The reserve agency, without capital of its own, bought the corn with loans at a staggering domestic interest rate, above 50 percent. Storage itself was expensive, and after a second bumper crop in 1999-2000, there were concerns that the untapped grain reserves would rot.

The donors felt adjustments were necessary. The starter-pack program now seemed too benevolent. Were farmers to be given fertilizer forever? they asked. If so, that would create a dependency that in the jargon of development economics was ''unsustainable.'' So the program was reconstructed as ''targeted inputs,'' cut in half to reach only the ''neediest'' of the destitute. As for the grain reserve, the donors, like the government, fretted over those gargantuan interest payments. To satisfy the debt, they suggested that the corn be sold, with future stocks kept to a modest 35,000 to 65,000 tons, considered enough to meet most emergencies until more grain could be imported.

Malawi has stunning skies, with a blue so bright and clouds so shapely that they seem to be the work of a cartoonist. Those skies are also fickle, suddenly exchanging a sunny disposition for an angry pout and unleashing thunderstorms that seem to hurl water rather than drop it. In February and March of 2001, as the harvest approached, the skies were angrier than usual, causing regional flooding. That brought the first clue of the trouble to come. This accumulating water kept the fields a hearty green, but the cornstalks, standing uncomfortably in shallow pools, failed to mature fully. Many a farmer was fooled by the deepness of color. They had thought they were going to have a good harvest and did not face the disappointing truth until it came time to pick.

Farmers were not the only ones fooled. Crop forecasters from the Agriculture Ministry underestimated the impact of the flooding on the corn harvest. These errors were compounded by a grossly wayward overestimation of the cassava and sweet potato yield, a false optimism perhaps bred from a false pride. The Agriculture Ministry was involved in a multimillion-dollar United States aid program for crop diversification. Field agents who reported high expectations for these roots and tubers were the same people whose job it was to encourage their planting. The net effect was to delay concern about the total food supply. Indeed, a surplus was predicted: if people ran out of corn, let them eat cassava.

By late summer, when the final estimates came in, the corn harvest was put at 1.9 million tons, about a third lower than the excellent crop of the year before. This was considered a bad though not a terrible yield. And yet to those attentive enough, something ominous was happening. In some areas, corn prices had increased more than fivefold, a sign that stocks were perilously low. Though neither the nation's preoccupied president, Bakili Muluzi, nor the donors were yet alarmed, the Agriculture Ministry was fretful enough to advocate a grain purchase. In September, a decision was announced to import corn from South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda.

As usual, the government asked the donors to foot the bill. The donors, in reply, inquired about the national grain reserves -- and were shocked to learn that they were entirely gone. Yes, the donors acknowledged, they had recommended the selling of most of it. But if the entire storehouse was empty, who bought it? And where was the money?

Answers were not forthcoming. That infuriated the always suspicious donors, so much so that the mystery of the missing grain overshadowed the unfolding fate of the fragile poor for several crucial months. This delay was tragic. By year's end, people were lining up at clinics to plead for food. Jos Kuppens, an activist Dutch priest, said he saw starving people resorting to meals of fodder, with one woman even thickening her gruel with sawdust. He recalled a hopelessly thin little girl he had seen at a Catholic hospital. He asked her where she was from. ''I had to bend close to hear her,'' he said. ''She could barely speak, and she said, 'njala,' which is the word for hunger. The sister told me: 'There's nothing we can do for a child like this. It's too late.'''

Despite the donors' unwillingness to pay the bill, the government tried to proceed with its plans to import 220,000 tons of corn. But a freak coincidence of disasters stalled deliveries: washed-out bridges, a derailed train, a port on fire. It also became clear that Malawi's neighbors faced a similar shortage. They began to vie to buy the same food.

A British agronomist named Harry Potter, dean of the foreign agricultural experts among the donors in Lilongwe, is a man far less inclined toward wizardry than his fictional namesake. Nevertheless, he saw a supernatural hand dispensing punishment.

''It was almost as if somebody up there had decided, Malawi, you have to be taught a lesson,'' he said. But cosmic reprimand or not, the consequences were of course grave only to the very poor and not to their nefarious officials.

Little grain would arrive in time for the start of the hungry months in December.

Famine is variously defined by scholars, though its common usage most often implies a large surge in hunger-related mortality. Some would even designate a minimum body count. Malawians, at least linguistically, make little distinction between ''hunger'' and ''famine'' except to say that famine is ''the hunger that kills.'' Perspective, of course, changes depending on whether you are studying the situation or starving within it. Stephen Devereux of the University of Sussex -- an expert on African food security -- talks about ''outsider'' and ''insider'' views of such crises. Outsiders presume famine to be an extraordinary event, while insiders see it as an intensification of what they already suffer.

The Nobel laureate Amartya Sen is the world's best-known authority on famine. He argues that such catastrophes do not occur in a ''functioning democracy,'' where a free press is a roving sentinel and elected governments have strong incentives to take preventive measures. If so, it is hard to say whether Malawi would be an exception. First, there is the matter of how well the nation's nine-year-old democracy qualifies as functioning. Then there is the question of whether the hunger that killed Robert Mkulumimba and Mdati Robert qualifies as famine.

By the beginning of the hungry months, starvation deaths were already being recorded within miles of the capital. Lilongwe seems a very un-Malawian city, with a scattering of big office buildings and fancy shopping malls. Notable on some thoroughfares are dozens of roadside ''coffin workshops,'' their carpenters steadily at work in the open air, taking morbid advantage of a rare growth industry. Capital Hill -- home to the government ministries -- is an isolated slope of manicured land, best reachable by car, far away from the masses.

For weeks, I tried to interview President Muluzi. Finally, I was informed that he saw no reason to see me since I had already spoken with his friend Friday Jumbe, the finance minister.

That conversation had seemed cordial enough, though on reflection, perhaps I was considered impertinent for asking about the missing grain reserves. At the time of the sale, Jumbe headed a quasi-governmental corporation that had physical control of the stored corn. A parliamentary committee had investigated the deals, and while the probe turned up little solid evidence, its report concluded that the reserves were ''mainly sold to politicians and individuals politically connected.'' Jumbe was faulted for failing to explain his recent financing of a luxury hotel in the city of Blantyre.

''It is true that some people bought the maize at a price of 4 or 5 kwacha, and then one day maize became scarce,'' the finance minister told me one morning in his office. ''That's business!'' Elegantly dressed in a three-piece suit, he was dismissive, and occasionally sarcastic, about the allegations. He said it was ''foolish'' to assume that he was a thief just because he owned a hotel and pointed out that the author of the damning report had been fired and that a revised investigation of the facts was in the works. ''If there was any theft of money, maybe, I don't know what, 100 or 200 or 300 kwacha -- but not big money. But the donors, that's where the bone of contention is. They are assuming that certain politicians bought this grain at a small price and made a killing.''

Indeed, that is -- and was -- the assumption. To this day -- after two years and five investigations -- the donors know little more than that some traders bought corn for very little and sold it for quite a lot, yet another scandalous story about people in the right place at the right time with the right friends, a Malawian Enron. Unfortunately, the donors' righteous pique played a part in the tardy recognition of the deadly hunger, as did Muluzi's willful ignorance. In February of last year, the president was still refuting any reports of a food crisis. ''Nobody has died of hunger,'' he insisted.

But by then, firm statistical proof had begun to appear in repeated health surveys. Also, hospital admissions for severe malnutrition were swiftly escalating far beyond the normal. At month's end, even Muluzi did a turnabout. On Feb. 27, he declared a state of emergency in a national broadcast -- 11 days after the death of Robert Mkulumimba.

Mkulumimba is one in a cluster of five villages, each with 35 to 60 households. Their boundaries reach deeply into one another, and it was sometimes possible to move between them simply by walking from hut to hut. Any visit required the permission of the village headman -- the chief -- who customarily then assumed the role of official escort. I was fortunate to be befriended by Elias Mitengo, a 50-year-old headman widely held in high regard. A poor farmer, he combined the gravitas of a diplomat with the easy humor of a kibitzer. He was chief of the village of Mdauma. And he was also Adilesi's son-in-law.

Elias said he had always tried to help his in-laws whenever he could. But last year, he often did not have enough food for even his own children. ''It was an impossible time,'' he said.

Being headman, an inherited job, included sensitive duties. The chief allocated land and mediated disputes and sometimes judged criminals. He was also the village marriage counselor and arbiter of property settlements in the event of divorce. Elias prided himself on absolute fairness. When I wanted to observe church on Sunday mornings, he went along and even addressed the congregations. But generally, he said, he no longer attended services. With five churches in the area, he worried about favoritism.

One morning, Elias invited me to a meeting under a stand of trees. Several chiefs were discussing a proper punishment for stealing food. Instant justice was being applied in some places, with the hungry crook forfeiting a hand. This, the headmen agreed, was too harsh. Yet when thieves were simply turned over to the police, they were released after a few days, and that seemed too lenient. A better penalty, the chiefs agreed, would be stiff fines -- perhaps three goats or chickens. But this was impractical. Thieves usually belonged to the poorest of families. The discussion went on and on without resolution.

For Elias, hungry thieves seemed less a problem than organized crime. In recent years, it was not uncommon for a truckload of men to descend during the night. Usually, they rustled livestock. But sometimes they emptied entire cornfields of ripe cobs. Elias decided to levy a 5 kwacha tax on each household, enough to pay vigilantes to guard the roads, waiting with axes and pangas and bows and arrows.

''These are not the best of days,'' he told me, laughing at his own understatement.

Actually, Elias had plunged into deep pessimism, something he was more likely to express after a few liters of chibuku, a cheap beer made from corn and millet. He said the njala, the hunger, was prying apart families, turning husbands and wives against each other. ''These women carry their vegetables to the trading center, and if they can't sell them, they sell themselves,'' he said. ''It's the poverty.'' Sometimes, he told me, he would call village meetings to speak out against prostitution, particularly addressing the young women. ''I tell them: 'You see your elders. They got to live this long because they kept themselves clean of promiscuity.''' He would invoke the threat of ''government disease.''

Men were hardly blameless, Elias said. Some were lazy. And of those who were not, some occasionally found work in other districts and then returned home triumphantly with a second wife. Fear of AIDS was also making men do crazy things. Some thought sex with a virgin cured the virus. In parts of Malawi, this superstition had led to rapes.

''Things were never like this before,'' Elias said.

While I had done no scientific sampling, it seemed that more than half the adults I met were not living with spouses. Women usually said they had thrown their husbands out. Adilesi's daughter Lufinenti was typical. Her husband, the father of her three children, had been gone from the village for three years. ''He used to be a hard worker, but when he made a lot of money, he wanted to marry more women, and I didn't want to be in a two-wife marriage,'' she said. At any rate, there was now no chance of his return. He had moved to the south and then died after a long illness, one of his friends had told her. Maybe it was AIDS, maybe tuberculosis, maybe both. ''They said he was always coughing,'' she said.

In the case of Mdati, Adilesi's deceased daughter, her husband was also described as a good worker, a man who could get construction jobs. But his ''sleeping around'' had become intolerable. ''He'd even take other women into their house,'' Lufinenti said. While she described these dalliances, at one point she mentioned parenthetically that the ''last'' of Mdati's sons was now living with his father in a different village. This unexpected detail confused me. For weeks, I had assumed that all four of Mdati's sons were among the many small boys I always saw nearby, playing with tops and homemade pull toys.

It was only then that I learned that the three youngest had died during these past months, a tragedy so within the parameters of the commonplace that it had not merited any special mention. The first boy died of malaria, the second of a rash and high fever.

The third, Legina Robert, perished only in December. He was 3 years old and very tiny, just another Malawian youngster with growth so stunted that he had yet to walk. Children warming themselves by a fire dropped him as they carelessly passed his body across the flames. The adults were in the fields when they heard frenzied calls for help. The little boy needed to be rushed to the hospital -- a three-hour journey by foot but only half that if they had been able to borrow one of the village's few bicycles. ''We looked, but we didn't find one,'' Lufinenti recalled. ''He died while I was carrying him on my back.''

Paradoxically, food was growing everywhere, the slender cornstalks nudging up against the roads, leaning along the hillsides, creeping down to the river's edge. Crops were wedged into the spare emptiness of the cities, spreading in half-ovals around office buildings, stores and saloons, reaching even the back entrances of the government ministries. To be in Malawi during the hot and wet growing season was to be embraced by a landscape of tantalizing abundance -- a perplexing sight in view of all the hunger.

But in Malawi, a visitor soon realizes that the lush color is a cruel tease. All those planted fields, all that greenness, are merely symbols of desperation. Crops appear in unlikely places because farmers feel a need to stretch their holdings. Those inescapable cornstalks are telltale of a nation growing food to fill its belly rather than to compete in world markets. Little economic development is taking place.

Always on arrival at Adilesi's house, my first question was ''What are you going to eat today?'' And each time I listened to the family's contingencies, that day's single meal dependent on some relative being lucky enough to get ganyu or Lufinenti being able to sell her foraged greens in the city. When a little money was earned, the family spent it frugally, never splurging on cornmeal but instead cooking gaga, a dish made from only the outer husks of the corn kernels, a sifted residue more commonly employed as fodder.

Adilesi's field is only a short walk from the house. The family's corn plants were puny for that late in the growing season, and many of the leaves were yellowish and droopy. Children broke off the least promising stalks and chewed them like sugar cane.

On one visit, I was accompanied by Ellard Malindi, the country's chief technical adviser for agriculture. He was a big-hearted man who talked easily with the farmers. A few months later, tragically, he would come down with cerebral malaria and die. But on that sunny day, he was at his vigorous best, and during a stroll through Adilesi's field, he moved from row to row, examining the sorry plants and shaking his head in frustration. ''We're standing on the richest soils in the entire country, maybe in southern Africa,'' he said as his arm cut an arc through the air. ''We're in the medium-altitude plateau. But the soil has become depleted by continuous planting, and it has lost its organic nutrients.''

Goliati Faisoni, Adilesi's oldest son, was with us. A skinny, sickly man with bloodshot eyes, he agreed with Malindi. The family would not be reaping much this year. And however much there was, they intended to eat it early, when the cobs were still new and green. The family was often too hungry to allow their crops to ripen fully. Last year, in fact, they used their green corn to feed the mourners at Mdati's funeral.

''Didn't you get a starter pack?'' Malindi asked Goliati.

The family had. But in their desperation they used the fertilizer incorrectly. They were supposed to apply the bag of mixed nutrients -- nitrogen, phosphate, potash and sulfur -- when they planted, then a second bag with urea when the stalks were knee high. Instead, the family combined the bags. Then, rather than concentrating on one quarter-acre, they spread it thinly over their entire field, hoping to outsmart science.

''There were also beans in the pack,'' Malindi said. ''Did you plant a bean crop?''

No, he confessed. The family had been unable to resist. They had eaten the beans.

Families starve because families lack money. In most cases, it is that simple.

But last year, while most of Mkulumimba went hungry, its chief, Daniel Mkulumimba, was getting by all right. I had often wondered about him. He was the one man in all five villages whom others considered wealthy. His tobacco field was only a 10-minute walk from Adilesi's door. ''He could easily help people, and sometimes he does,'' Elias, the headman, told me. ''But it's not his nature. He mostly takes care of his own.''

By American standards, Daniel was hardly rich. He, too, lived in a one-room house, though it was a bigger room, and it was covered with a roof that did not leak. He owned an ox cart, a bicycle, six donkeys and four goats. Besides corn and tobacco, he grew cabbage, lettuce, turnips and sugar cane on his 15 acres of land. He fertilized his fields, and the healthy cornstalks towered above him. He had two wives and a pot belly.

I wanted to understand why Daniel had not done more to help. When I posed the question, he considered it for a few seconds before saying, ''When the food situation is very serious, the rich and the poor are the same, and it's everyone for himself.'' I reminded him that his cousin Robert had actually died of starvation. ''As the chief, I'm not supposed to help one particular family,'' he replied. ''I'm chief of the whole village.''

For me, Daniel came to represent the ''haves'' of the world. They do assist Africa, though not with a strenuous effort, certainly not in proportion to the hunger and the disease and the benumbing poverty. Indeed, in relation to their gross domestic product, donor nations are now spending considerably less on foreign assistance than they were a decade ago. Among wealthy countries, the United States spends the lowest percentage of all, something President Bush is understandably reluctant to mention when he talks about Africa.

Many experts debate whether aid does more harm than good. Certainly Africa's problems are immense and confounding: paralyzing debt, sorry infrastructure, depleted soil, meager exports, bad government and ethnic and tribal warfare. The majority of Africa's poorest countries have average incomes below the level of Western Europe at the start of the 17th century, according to the distinguished economic historian Angus Maddison.

Unlike the days when structural adjustments were seen as direct routes to poverty reduction, now there seems to be little consensus on what to try next. Proposals tend to be modest. In Lilongwe, I heard one idea after another: soil renourishment, manufacturing schemes, public-service jobs, small-scale irrigation. Lawrence Rubey, the American booster of free enterprise, showed me a bag of chilies grown for export to Germany. ''Niche marketing,'' he said, in much the same way ''plastics'' was advised in ''The Graduate.''

Maybe chili peppers can be one of the answers, maybe not. But in the meantime, even if poverty and hunger seem unconquerable, famine surely can be overcome. Only our indifference -- only our neglect -- allows it to persevere. In Malawi, the timely distribution of fertilizer ought to be preferable to the inevitability of emergency food. That is what every farmer in the villages asked for: if you give us fertilizer, or a reasonable way to buy it, we'll manage for ourselves from one hungry season to the next.

As I heard these sentiments, I would always nod sympathetically, writing the anguished words in my notebook. The people I met were invariably gracious, even though I knew an unspoken tension existed between us. After all, they were hungry, and I had the means to change that in my wallet, as easily as I handed my kids lunch money back in America. But I wanted to understand how people coped with hunger, and handouts would have made that impossible. So I had made a decision in advance: if I met people who seemed gravely ill, I would take them to the hospital and pay their expenses. (That happened twice.) Otherwise, I'd give no one money until the reporting was done.

And that day gave me as much relief as it gave them -- perhaps more. It is awful to be with the hungry, to watch them ebb and falter and scrounge.

''You ask so many questions about death!'' Adilesi said to me during one of my final visits. ''It is hard on us. We believe that when you talk about the dead, you get visits by their spirits at night. When are the questions about the dead going to stop?''

I apologized but said that I had come to learn about hunger and that I had learned a lot.

I thanked her for that. And that is when she and her daughter thought to share with me their ''ingenious'' trick, something she thought every human being ought to know.

If I were ever so hungry I could no longer work, they advised me, there was a way for a determined mind to outfox a hollow stomach. ''Tie some cloth tightly around your waist right at the navel,'' Lufinenti said. ''Make it as tight as you can.''

For a few hours, you can fool your belly into thinking that it's full.

Barry Bearak is a staff writer for the magazine. His last article was about the reconstruction of Afghanistan.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from the New York Times Magazine of July 13, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |