| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted May 22, 2004 |

THINK TANK |

Michael Erard |

|

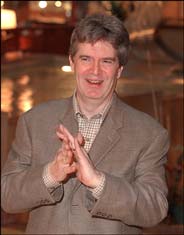

| Mark Peristein, for The New York Times |

| Ronald S. Burt, a sociologist, says: "Creativity is an import-export game. It's not a creation game." |

Got a good idea? Now think for a moment where you got it. A sudden spark of inspiration? A memory? A dream? Most likely, says Ronald S. Burt, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, it came from someone else who hadn't realized how to use it. "The usual image of creativity is that it's some sort of genetic gift, some heroic act," Mr. Burt said. "But creativity is an import-export game. It's not a creation game."

Mr. Burt has spent most of his career studying how creative, competitive people relate to the rest of the world, and how ideas move from place to place. Often the value of a good idea, he has found, is not in its origin but in its delivery. His observation will undoubtedly resonate with overlooked novelists, garage inventors and forgotten geniuses who pride themselves on their new ideas but aren't successful in getting them noticed. "Tracing the origin of an idea is an interesting academic exercise, but it's largely irrelevant," Mr. Burt said. "The trick is, can you get an idea which is mundane and well known in one place to another place where people would get value out of it."

Mr. Burt, whose latest findings will appear in the American Journal of Sociology this fall, studied managers in the supply chain of Raytheon, the large electronics company and military contractor based in Waltham, Mass., where he worked until last year. Mr. Burt asked managers to write down their best ideas about how to improve business operations and then had two executives at the company rate their quality. It turned out that the highest-ranked ideas came from managers who had contacts outside their immediate work group. The reason, Mr. Burt said, is that their contacts span what he calls "structural holes," the gaps between discrete groups of people.

"People who live in the intersection of social worlds," Mr. Burt writes, "are at higher risk of having good ideas."

People with cohesive social networks, whether offices, cliques or industries, tend to think and act the same, he explains. In the long run, this homogeneity deadens creativity. As Mr. Burt's research has repeatedly shown, people who reach outside their social network not only are often the first to learn about new and useful information, but they are also able to see how different kinds of groups solve similar problems.

Mr. Burt began developing his idea about "structural holes" — the notion that people can find opportunities for creative thinking where there is no social structure — as a graduate student at the University of Chicago in the 1970's. A student of the eminent sociologist James Coleman, he was assigned to study patterns of exchange between companies using a technique called block modeling, which classifies individuals and organizations according to a large amount of data on what they buy, who they know and more. Structural holes between companies was a theme in his 1977 dissertation and became a focus in his 1992 book, "Structural Holes," which applied it to individual behavior.

In 2000 Mr. Burt took the idea of structural holes to Raytheon, where he was hired to help integrate a group of recent acquisitions. What he discovered was that many potentially good ideas died at the hands of those who brought them. Raytheon managers had a wide gap between coming up with good ideas and making them happen.

"Although managers with discussion partners in other groups were positioned to spread good ideas across business units," he writes, "the people they cited for idea discussion were overwhelmingly colleagues already close in their informal discussion network." The result was that the ideas were not developed. Instead, he says, they should have had discussions outside their typical contacts, particularly with what calls an informal boss, a person with enough power to be an ally but not an actual supervisor.

Wayne Baker, a professor of management and organization at the University of Michigan Business School, said the structural holes approach reminds people to continually open up their networks, which naturally drift toward closure.

Mr. Burt's theory may offer some caution for people who have been trying to enlarge their social networks on the Web by using "social software" at sites like Friendster, Ryze and MySpace. The idea underlying these computer hookups is that the better connected you are, the more valuable social capital you will have. But Mr. Burt's work suggests the opposite: expanding your network may fill in the structural holes, eliminating their creative benefits. By linking everyone together indiscriminately, it becomes increasingly difficult to reach outside your regular contacts and surprise anyone with a new idea.

"My M.B.A. students tell me all the time: `Don't disseminate this. This should be our little secret,' " Mr. Burt said. But he tells them there are more than enough structural holes to go around. The reason? Laziness, mostly. "Often people are like sheep eating grass," Mr. Burt said. "They're so focused on what's right in front of them, they don't look for the whole."

Mr. Baker, who has evaluated thousands of personal social networks with a Web-based tool (www.humaxnetworks.com), argues that neither model offers a formula for success, though. "If there is a rule of thumb in practice," he said, "it is to have a hybrid network that has features of closure and structural holes."

Mr. Burt offers somewhat different advice: "The easiest way to feel creative is to find people who are more ignorant than yourself."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of May 22, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |