| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted February 14, 2004 |

|

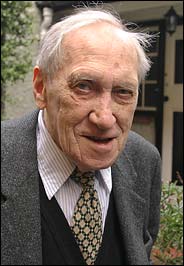

Jonathan Player for The New York Times |

| Lezek kolakowski, shown at his home in Oxford, England, is a Polish philosopher whose thinking helped buttress Solidarity. He won a million-dollar humanities prize. |

| When Philosophy Makes a Difference |

By SARAH LYALL |

OXFORD, England — When the Library of Congress first talked to the 76-year-old Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski, it was to ask him to nominate candidates for a new $1 million humanities prize. So he was taken aback when the Library later called to tell him he had won the award himself.

If Dr. Kolakowski was surprised, most Americans were probably puzzled; his name is not well known in the United States. But for those who wonder why this philosopher was selected for the first John W. Kluge Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Humanities and Social Sciences, Dr. James H. Billington, the librarian of Congress, explained it in his announcement three months ago: "Very rarely can one identify a deep, reflective thinker who has had such a wide range of inquiry and demonstrable importance to major political events in his own time."

Born in Poland and ejected from his university position and from the Communist Party in the 1960's because of his increasingly anti-orthodox beliefs, Dr. Kolakowski in exile became a major figure in the Polish Solidarity movement in the 1980's. His three-volume dissection of Marxism, "Main Currents of Marxism" (1978), is considered a definitive work on the subject. But he is also a lucid and engaging essayist whose books and other writings touch on subjects like Spinoza, Kant, modernism, authority and free will, and the relevance of philosophy in everyday life.

Despite such impressive credentials, Dr. Kolakowski remains a modest man, deflecting personal questions. "You don't need to know about my life," he said in an interview as he sipped coffee in the living room of his house in northern Oxford, where until several years ago he was a research fellow at All Souls College.

Likewise, he declined to reveal just how he reacted to the news of his recent award. Yes, but how about the cash? He looked down at his cup and gave a sly smile. "I never had great problems with spending money," he said.

The life of Dr. Kolakowski, whose name is pronounced LESH-ehk ko-wah-KUHV-skee, was torn apart twice, first by Nazism, then by Communism. The son of intellectuals, he was moved with his family after the German invasion to a succession of small towns and villages in central Poland and was forbidden to attend school. "The Germans closed the schools for the Poles," he said. "The great idea was that Poles be swineherds for the Germans and be left illiterate."

He nonetheless read widely and surreptitiously and after the war got a doctorate in philosophy from Warsaw University. At first he embraced doctrinaire Marxism as an antidote to Nazism and as a compelling utopian ideal. "I disliked intensely a certain tradition in Polish culture — right-wing, clericalist, anti-Semitic — and belonged to the left milieu during the war," he explained. "After five years of horrors under the Germans, we greeted the Red Army as a liberation."

Early on, he says, he could see that what he was signing on to was not what it made itself out to be. But it was not until he went to Moscow for three months in 1950, as part of a program for promising young Marxist intellectuals, that he had his ideological awakening, discovering that Marxism's rich ideological rhetoric jarred with its thin cynical reality.

"One could see the cultural degradation — the poor level of intellectual life of the leading luminaries of Soviet science and ideology, the poor level of art and so on," he said.

Back in Poland he rose through the ranks at Warsaw University, where he eventually became chairman of the history of philosophy section, while attacking Marxism in pungent, often satirical writings that put him increasingly at odds with the establishment. He began to argue for a humanist socialism or a socialist humanism, and became the leading thinker behind the "Polish October" movement, made up of intellectuals agitating for reform.

Dr. Kolakowski's influential critique of Stalinism, "What Is Socialism?," was banned by the government, among other writings, but circulated widely among other disillusioned intellectuals. He was ejected from the party in 1966 and fired from his university job two years later. He then left the country, along with his wife, a psychiatrist, and their daughter, taking a visiting professorship at McGill University in Toronto. "I expected that my absence from Poland would be two years, but it extended to 20," he said.

When the opposition movement began gathering strength in Poland in the 1970's and 80's, Mr. Kolakowski's writings had a pivotal ideological effect on those in Poland and a galvanizing effect on those outside the country, particularly after martial law was imposed in 1981. He plays down his role, though, saying that he was just one of many intellectuals whose writings and political work were influential and that he performed "small services."

At one point he asserted in English that "I only have one language — Polish — although I pretend to speak in various languages." (Those are French, German and Russian besides English).

Speaking of the demise of the Communist system, Dr. Kolakowski said, "This ideology was supposed to mold the thinking of people, but at a certain moment it became so weak and so ridiculous that nobody believed in it, neither the ruled nor the rulers."

With the fall of Communism, Dr. Kolakowski returned to earlier interests, including Spinoza. He wrote books on the history of philosophy and the philosophy of religion, on ethics and metaphysics. His work ranges from historical examinations of European Christian movements in the 16th and 17th centuries to satirical plays and allegorical fables in which, among other things, he subjects stories from the Old Testament to modern-day dialectical reason. In an earlier book, "Conversations With the Devil" (1972), a wily Satan debates figures from myth and history — Orpheus, Héloïse, Luther, St. Peter the Apostle, St. Bernard — and even participates in a "metaphysical press conference." His newest book, "The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers" (St. Augustine's Press), should soon be in stores.

The critic George Gomori wrote of Dr. Kolakowski: "This might well be the gist of his message: You cannot love both truth and authority. You have to choose, without dogmas, often rethinking your own premises. Kolakowski's is a philosophy for grown-ups."

In contrast to many modern-day philosophers whose writings can be practically unintelligible, Dr. Kolakowski writes in a way that even nonacademics can readily understand.

Dr. Prosser Gifford, director of scholarly programs at the Library of Congress, led the selection process that resulted in Dr. Kolakowski's winning the Kluge prize. He said: "I don't want to put down my academic colleagues, but some aspects of humanities in recent years have gotten very arcane and full of jargon."

"We're wrestling with fundamental issues, and these ought to be understandable to people who are not academics and not professionally committed to this sort of endeavor. Dr. Kolakowski does that."

Dr. Kolakowski also stands out for his disarming frankness in admitting that even unanswerable questions are worth asking. In "Metaphysical Horror" (1988), for instance, he writes playfully of people's fear of "impossible questions" and sends up his life's work, in a sense, in the book's first sentence.

"A modern philosopher who has never experienced the feeling of being a charlatan is such a shallow mind that his work is probably not worth reading," he writes. Asked about this assertion, he laughed and allowed that sometimes he feels like a charlatan but that he doesn't mind because his charlatanish thoughts are counterbalanced by "the feeling that even a charlatan can can fulfill a useful role."

Engaging with fundamental issues, Dr. Kolakowski said, is fundamental to experience, no matter how fruitless it seems at times.

"There is a mental compulsion to ask metaphysical, epistemological and ethical questions," he said. "It is not that one is happy in thinking about it, but these questions are difficult to get rid of."

He added: "There are no definitive answers, but there are ways of approaching questions which give you the feeling that you are on the right track, even though you won't reach the expected goal."

"Nevertheless," he said, "this position is not dramatic. It is not terrible. One can live with it."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, Saturday, February 14, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |