| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted December 30, 2007 |

Heil Woodrow |

|

|

|

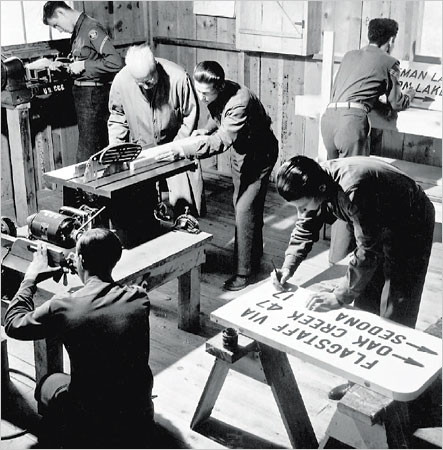

PHOTOGRAPH BY HEBERT GEHR/TIME LIFE PICTURES - GETTY IMAGES |

|

| Members of the Civilian Conservation Cops work on road signs. |

By DAVID OSHINSKY |

COMING of age in the 1960s, I heard the word “fascist” all the time. College presidents were fascists, Vietnam War supporters were fascists, policemen who tangled with protesters were fascists, on and on. To some, the word smacked of Hitler and genocide. To others, it meant the oppression of the masses by the privileged few. But one point was crystal clear: the word belonged to those on the political left. It was their verbal weapon, and they used it every chance they got.

| LIBERAL FASCISM |

| The Secret History of the |

| American Left From |

| Mussolini to the Politics |

| of Meaning. |

| By Jonah Goldberg. |

| 487 pp. Doubleday. $27.95. |

Forty years have passed and not much has changed, complains Jonah Goldberg, a conservative columnist and contributing editor for National Review. Leftists still drop the “f word” to taint their opponents, be they global warming skeptics or members of the Moral Majority. The sad result, Goldberg says, is that Americans have come to equate fascism with right-wing political movements in the United States when, in fact, the reverse is true. To his mind, it is liberalism, not conservatism, that embraces what he claims is the fascist ideal of perfecting society through a powerful state run by omniscient leaders. And it is liberals, not conservatives, who see government coercion as the key to getting things done.

“Liberal Fascism” is less an exposé of left-wing hypocrisy than a chance to exact political revenge. Yet the title of his book aside, what distinguishes Goldberg from the Sean Hannitys and Michael Savages is a witty intelligence that deals in ideas as well as insults — no mean feat in the nasty world of the culture wars.

According to Goldberg, fascism in America predated the regimes of Mussolini and Hitler. He believes that Woodrow Wilson turned the United States into a “fascist country, albeit temporarily” during World War I. Americans in 1917 were reluctant to join the slaughter in Europe. Their nation hadn’t been attacked; there was no defining event — a Fort Sumter or Pearl Harbor — to rally public support. So Wilson formed the country’s first propaganda ministry, the Committee on Public Information, to teach people what they were up against. The devil became German militarism — the merciless Hun — and Americans were encouraged to lash out at those of German ancestry inside the United States. Vigilante groups arose to mete out justice and spy on fellow citizens. Congress passed draconian laws banning “abusive” and “disloyal” language against the government and its officials. The Post Office revoked the mailing privileges of hundreds of antiwar publications, effectively shutting them down. Rarely if ever in American history has dissent been so effectively stifled.

At the same time, Wilson formed numerous boards to regulate everything from the production of artillery pieces to the price of a lamb chop. The result, Goldberg argues, was the birth of a socialist dictatorship that “whipped, cajoled and seduced American industry into the loving embrace of the state.” Though partly dismantled after the war, this model, we are told, became the blueprint for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Goldberg is less convincing here because he can’t get a handle on Roosevelt’s admittedly elusive personality. He treats Wilson as a serious thinker, rigidly focused on his goals, but portrays Roosevelt as a classic dilettante, shallow and detached. For Goldberg, even the president’s greatest skill — his ability to communicate with the masses — was negated by his failure to chart a steady course and stick to it. One is left to ponder how the outlines of America’s modern welfare state emerged from such a lazy, superficial mind.

In attempting to link Roosevelt to the fascism that enveloped Europe in these years, Goldberg highlights examples like the Civilian Conservation Corps, which offered a paycheck and military discipline to unemployed young men from the cities, and the National Recovery Administration, which was intended to spur industrial production through centralized planning. But it’s absurd to view the C.C.C. as the American version of Hitler Youth, and the N.R.A. — heavy on slogans, light on coercion — was so ineffective that Roosevelt heaved a sigh of relief when it was declared unconstitutional in 1935. Oddly, Goldberg has less to say about issues more likely to bolster his case, like the enormous growth of executive power under Roosevelt and his ill-fated attempt to “pack” the United States Supreme Court.

Goldberg acknowledges that Wilson and Roosevelt faced legitimate national emergencies — a world war and an economic collapse. But subsequent presidents have invented false crises to roil the masses, he claims, and John F. Kennedy did it best. “It is not a joyful thing to impugn an American hero and icon with the label fascist,” Goldberg writes, but how else does one explain his popularity? The answer lies not in Kennedy’s record, which Goldberg assures us was slim, but rather in his cold-war brinkmanship, his “adrenaline-soaked” appeals to national service and martial values, and, of course, the Nazi-like cult of personality that he buffed to gleaming perfection.

Is something missing here? Goldberg races from Wilson to Roosevelt to Kennedy and on to Bill Clinton with barely a glance at what happened in between. The reason is simple: for Goldberg, fascism is strictly a Democratic disease. This allows him to dispose of the politics of the 1920s in a single sentence. “After the Great War,” he writes, “the country slowly regained its sanity.” What Goldberg may not know — or is afraid to tell us — is that the 1920s were anything but sane. This was the decade, after all, that contained the largest state-sponsored social experiment in the nation’s history — Prohibition — and it lasted through three Republican administrations before Franklin Roosevelt ended it in 1933. The 1920s also saw the explosive spread of the Ku Klux Klan in the Republican Midwest, a virtual halt to legal immigration under the repressive National Origins Act and an angry grass-roots backlash against the teaching of evolution in public schools.

Goldberg briefly enters the Eisenhower 1950s to tease liberals for whining about the supposedly trivial impact of McCarthyism. “A few Hollywood writers who’d supported Stalin and then lied about it lost their jobs,” he says. What’s the big deal? For the Reagan 1980s there is near-silence — hardly a word. I had entertained the slim hope that Goldberg might consider the “fascist” cult of personality surrounding Reagan’s 1984 “Morning in America” hokum (“Prouder, Stronger, Better”). But, alas, such scrutiny is reserved only for the Clinton presidential campaign of 1992, with its “Riefenstahlesque film of a teenage Bill Clinton shaking hands with President Kennedy.” Indeed, even George W. Bush’s spectacularly staged landing on an aircraft carrier in full battle regalia to declare “mission accomplished” in Iraq escapes notice here. It doesn’t take a village for Goldberg to play the fascist card; a single Democrat will do.

The final chapters of “Liberal Fascism” are a rant, often deliciously amusing, against America’s numerous liberal-fascist elites. In unexciting times, when there are no calamities to be addressed, liberals push a more robust social agenda, Goldberg claims, using the state and the friendly news media to tar opponents of, say, affirmative action or same-sex marriage as bigots, fanatics and fools. The task facing conservatives, he adds, is to hold liberals accountable for these jackboot tactics. “For at some point,” Goldberg writes, “it is necessary to throw down the gauntlet, to draw a line in the sand, to set a boundary, to cry at long last, ‘Enough is enough.’”

These are familiar words, eerily reminiscent of the “adrelaline-soaked” clichés of John F. Kennedy as he railed against Soviet expansion around the globe. But I dare not call them fascist. That would be unfair. David Oshinsky, who holds the Jack S. Blanton chair in history at the University of Texas, is the author of “A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book Review, of Sunday, December 30, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |