| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted July 28, 2009 |

|

When Debtors Decide to Default |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

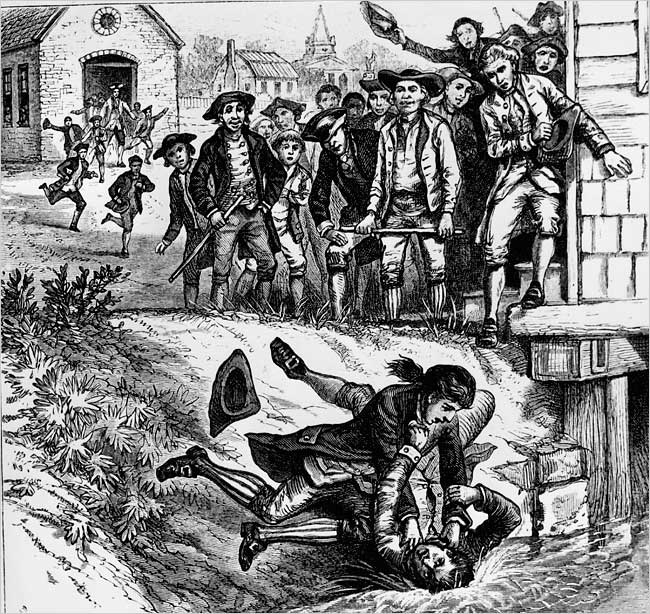

ENGRAVING FROM HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES |

|

| GETTING ANGRY In 1786, poor farmers in Massachusetts rebelled when creditors came calling: |

|

By DAVID STEREITFELD |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |