COLLEGE PARK, Md. — In another time or place, the game of “What Are You?” that was played one night last fall at the University of Maryland might have been mean, or menacing: Laura Wood’s peers were picking apart her every feature in an effort to guess her race.

Race Remixed

|

Black? White? Asian? More Young Americans Choose all of the Above |

|

|

|

|

STEPHEN CROWLEY/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

|

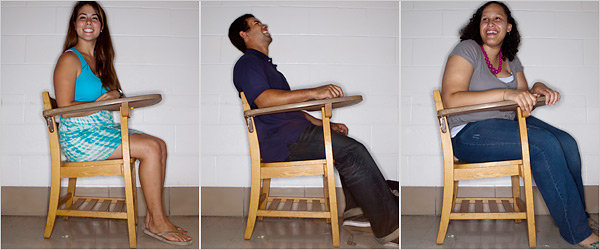

|

From left: Shannon Palmer, Japanese/Irish; Vasco Mateus, Portuguese/African-American/Haitian; Laura Wood, black/white. More Photos » |

|

|

By SUSAN SAULNY |

Race Remixed

A New Sense of Identity

Articles in this series will explore the growing number of mixed-race Americans.

Multimedia

“How many mixtures do you have?” one young man asked above the chatter of about 50 students. With her tan skin and curly brown hair, Ms. Wood’s ancestry could have spanned the globe.

“I’m mixed with two things,” she said politely.

“Are you mulatto?” asked Paul Skym, another student, using a word once tinged with shame that is enjoying a comeback in some young circles. When Ms. Wood confirmed that she is indeed black and white, Mr. Skym, who is Asian and white, boasted, “Now that’s what I’m talking about!” in affirmation of their mutual mixed lineage.

Then the group of friends — formally, the Multiracial and Biracial Student Association — erupted into laughter and cheers, a routine show of their mixed-race pride.

The crop of students moving through college right now includes the largest group of mixed-race people ever to come of age in the United States, and they are only the vanguard: the country is in the midst of a demographic shift driven by immigration and intermarriage.

One in seven new marriages is between spouses of different races or ethnicities, according to data from 2008 and 2009 that was analyzed by the Pew Research Center. Multiracial and multiethnic Americans (usually grouped together as “mixed race”) are one of the country’s fastest-growing demographic groups. And experts expect the racial results of the 2010 census, which will start to be released next month, to show the trend continuing or accelerating.

Many young adults of mixed backgrounds are rejecting the color lines that have defined Americans for generations in favor of a much more fluid sense of identity. Ask Michelle López-Mullins, a 20-year-old junior and the president of the Multiracial and Biracial Student Association, how she marks her race on forms like the census, and she says, “It depends on the day, and it depends on the options.”

They are also using the strength in their growing numbers to affirm roots that were once portrayed as tragic or pitiable.

“I think it’s really important to acknowledge who you are and everything that makes you that,” said Ms. Wood, the 19-year-old vice president of the group. “If someone tries to call me black I say, ‘yes — and white.’ People have the right not to acknowledge everything, but don’t do it because society tells you that you can’t.”

No one knows quite how the growth of the multiracial population will change the country. Optimists say the blending of the races is a step toward transcending race, to a place where America is free of bigotry, prejudice and programs like affirmative action.

Pessimists say that a more powerful multiracial movement will lead to more stratification and come at the expense of the number and influence of other minority groups, particularly African-Americans.

And some sociologists say that grouping all multiracial people together glosses over differences in circumstances between someone who is, say, black and Latino, and someone who is Asian and white. (Among interracial couples, white-Asian pairings tend to be better educated and have higher incomes, according to Reynolds Farley, a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan.)

Along those lines, it is telling that the rates of intermarriage are lowest between blacks and whites, indicative of the enduring economic and social distance between them.

Prof. Rainier Spencer, director of the Afro-American Studies Program at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and the author of “Reproducing Race: The Paradox of Generation Mix,” says he believes that there is too much “emotional investment” in the notion of multiracialism as a panacea for the nation’s age-old divisions. “The mixed-race identity is not a transcendence of race, it’s a new tribe,” he said. “A new Balkanization of race.”

But for many of the University of Maryland students, that is not the point. They are asserting their freedom to identify as they choose.

“All society is trying to tear you apart and make you pick a side,” Ms. Wood said. “I want us to have a say.”

The Way We Were

Americans mostly think of themselves in singular racial terms. Witness President Obama’s answer to the race question on the 2010 census: Although his mother was white and his father was black, Mr. Obama checked only one box, black, even though he could have checked both races.

Some proportion of the country’s population has been mixed-race since the first white settlers had children with Native Americans. What has changed is how mixed-race Americans are defined and counted.

Long ago, the nation saw itself in more hues than black and white: the 1890 census included categories for racial mixtures such as quadroon (one-fourth black) and octoroon (one-eighth black). With the exception of one survey from 1850 to 1920, the census included a mulatto category, which was for people who had any perceptible trace of African blood.

But by the 1930 census, terms for mixed-race people had all disappeared, replaced by the so-called one-drop rule, an antebellum convention that held that anyone with a trace of African ancestry was only black. (Similarly, people who were “white and Indian” were generally to be counted as Indian.)

It was the census enumerator who decided.

By the 1970s, Americans were expected to designate themselves as members of one officially recognized racial group: black, white, American Indian, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Korean or “other,” an option used frequently by people of Hispanic origin. (The census recognizes Hispanic as an ethnicity, not a race.)

Starting with the 2000 census, Americans were allowed to mark one or more races.

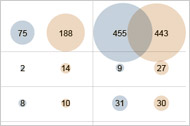

The multiracial option came after years of complaints and lobbying, mostly by the white mothers of biracial children who objected to their children being allowed to check only one race. In 2000, seven million people — about 2.4 percent of the population — reported being more than one race.

According to estimates from the Census Bureau, the mixed-race population has grown by roughly 35 percent since 2000.

And many researchers think the census and other surveys undercount the mixed population.

The 2010 mixed-race statistics will be released, state by state, over the first half of the year.

“There could be some big surprises,” said Jeffrey S. Passel, a senior demographer at the Pew Hispanic Center, meaning that the number of mixed-race Americans could be high. “There’s not only less stigma to being in these groups, there’s even positive cachet.”

Moving Forward

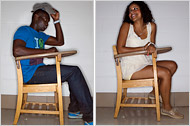

The faces of mixed-race America are not just on college campuses. They are in politics, business and sports. And the ethnically ambiguous are especially ubiquitous in movies, television shows and advertising. There are news, social networking and dating Web sites focusing on the mixed-race audience, and even consumer products like shampoo. There are mixed-race film festivals and conferences. And student groups like the one at Maryland, offering peer support and activism, are more common.

Such a club would not have existed a generation ago — when the question at the center of the “What Are You?” game would have been a provocation rather than an icebreaker.

“It’s kind of a taking-back in a way, taking the reins,” Ms. López-Mullins said. “We don’t always have to let it get us down,” she added, referring to the question multiracial people have heard for generations.

“The No. 1 reason why we exist is to give people who feel like they don’t want to choose a side, that don’t want to label themselves based on other people’s interpretations of who they are, to give them a place, that safe space,” she said. Ms. López-Mullins is Chinese and Peruvian on one side, and white and American Indian on the other.

That safe space did not exist amid the neo-Classical style buildings of the campus when Warren Kelley enrolled in 1974. Though his mother is Japanese and his father is African-American, he had basically one choice when it came to his racial identity. “I was black and proud to be black,” Dr. Kelley said. “There was no notion that I might be multiracial. Or that the public discourse on college campuses recognized the multiracial community.”

Almost 40 years later, Dr. Kelley is the assistant vice president for student affairs at the university and faculty adviser to the multiracial club, and he is often in awe of the change on this campus.

When the multiracial group was founded in 2002, Dr. Kelley said, “There was an instant audience.”

They did not just want to hold parties. The group sponsored an annual weeklong program of discussions intended to raise awareness of multiracial identities — called Mixed Madness — and conceived a new class on the experience of mixed-race Asian-Americans that was made part of the curriculum last year.

“Even if someone had formed a mixed-race group in the ’70s, would I have joined?” Dr. Kelley said. “I don’t know. My multiracial identity wasn’t prominent at the time. I don’t think I even conceptualized the idea.”