| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted June 5, 2003 |

| Violent pro-government gangs still prevalent in Haiti's politics |

|

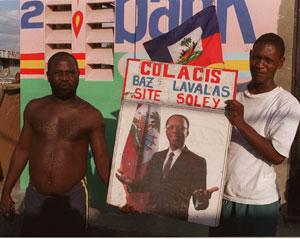

| SUPPORT: Duquesne Bauplan, left and Maxo Gracius run a grass-roots group in the Cite-Soleil slum. Such groups have garnered a reputation for political violence and terrorizing President Aristide opponents. Chantal Regnault for The Herald |

|

Violent pro-goPORT-AU-PRINCE -- James swaggers in his crisp blue jeans, a government ID tag flashing against his Hawaiian shirt. Security Team, Mayor, the badge says. ''When the government is in trouble, they come to me,'' the 22-year-old boasts.

``When the president needs some political backup, we organize demonstrations. . . I take my men and go.'' Young and brash, James heads one of dozens of so-called grass-roots organizations in Haiti -- groups that started out seeking to bring basic rights to the poor and counted among President Jean-Bertrand Aristide's most loyal supporters.

But he's also a gun-toting gang leader who moves seamlessly between lunch with the mayor of Cite-Soleil and managing turf wars. Groups like his have garnered such a reputation for political violence and terrorizing Aristide's opponents that they are called chimere -- French for a mythical fire-breathing monster, a demon with a lion's head, goat's body and serpent's tail. Nearly a decade after U.S. troops restored Aristide to power -- trying to foment democracy in a country plagued by coups d'etat, death squads and authoritarian rule -- a political gang culture still pervades.

They encourage political support for Aristide's government and enforce it as well, sometimes using heavy-handed methods -- a threat broadcast on a live radio show; a shotgun-shell casing placed in a prominent journalist's mailbox; a reporter hacked to death with a machete after having an opposition member on his show.

Haitian immigrants pleading for asylum in Florida have claimed these groups have beaten them, and forced them into hiding because they have spoken out against the government or refused to join the governing Family Lavalas party.

Aristide has denounced the violence these groups cause and suggests the raucous supporters are actually opponents trying to sully his name.

''It is not easy to distinguish which ones are really supporting us when they are causing violence,'' Aristide said during an interview with The Herald in December.

Some also have criticized these groups as mere mercenaries -- paid in cash or with no-show government jobs.

But human rights activists and diplomats complain the organizations enjoy virtual immunity. They point to the case of gang leader Amiot Metayer of the Cannibal Army -- an escaped fugitive implicated in a political murder and accused of burning down dozens of houses in a gang war.

Last month, a judge dropped the last charges against him. Days later, the burly Metayer burst into a news conference and announced he was ready to get back into Haiti's political fray.

Analysts also blame the groups in part for the country's crime problem.

''When you go below the surface, these gangs are heavily involved in the trafficking of arms, the drug trade,'' said a Western diplomat who has served in Haiti for several years.

These groups aren't just linked to criminal enterprises, the diplomat said. ``They are one and the same.''

The root support for these groups lies in neighborhoods like La Saline, the shantytown where Aristide was a parish priest, preaching liberation theology and advocating democracy.

Rene Civil, 31, a son of peasant farmers, spent his Sundays at Aristide's church, St. Jean Bosco. The two became friendly, he said. ''He was a man of vision. He was denouncing all that was going on, the repressive structure of the army . . . We admired his courage,'' Civil said.

Today Civil heads the Youth Popular Power league, which meets at St. Jean Bosco, even though the church -- an important symbol -- was all but destroyed in an attack on Aristide's life in 1988.

Civil is one of the most public faces behind these groups. Last fall, he was behind a protest during which Aristide supporters placed tires and burning barricades at key intersections, closing down the capital. Most people stayed home in fear.

Though he says he is still friendly with Aristide -- a visit to the National Palace last December was frowned upon by international observers -- he insists his group is independent of the government. But he clearly enjoys some ties to officials: An administrator at the government-run port, Civil showed up to an interview in a state telephone company truck, escorted by a man with a pistol strapped to his thigh who he said worked for the Haitian National Police. Civil has received threats, he explained, and needs the protection.

Civil works directly with groups from Cite-Soleil, he said, including the one run by the young gang leader James.

For him, politics is a family tradition -- his parents, both Aristide militants, were shot by military men for their activism, he said. He supports Aristide, he added, because he believes the president pays attention to his neighborhood.

''I'm 22, and I've been able to meet the president . . . my senator. I've talked to the chief of police,'' James said. ``I never would have been able to do that before.''

So when armed men stormed the National Palace on Dec. 17, 2001 -- in what the government says was a coup attempt -- the gang leader gathered up supporters. They stood watch at the back door and exchanged gunfire as the intruders fled.

''I got this on the 17th of December,'' Duquesne Bauplan, 34, another Cite-Soleil leader who works for the city sanitation and water companies, said pointing to a patch of skin puckered up like a kiss on his belly.

In the wake of the attack, hundreds of Aristide supporters ransacked, and in many cases destroyed, the homes and headquarters of opposition members. At least six people died in the chaos. The Organization of American States, which called the events one of the most ''awful'' chapters in Haitian history, later determined the mysterious raid wasn't a coup attempt. Meanwhile, opposition members cried the palace raid was deliberatedly used as a way to crack down on Aristide's opponents.

Bauplan and Civil shrug off the name chimere, and its implications.

First, Civil is quick to point out at that the government has armed opponents -- including a mysterious group of former Haitian army troops in central Haiti, who have been blamed for several killings, and attacks on two police stations and a power plant. Recently, former Haitian army officers were arrested in the Dominican Republic for allegedly plotting another coup, though they were later released.

''We created real change. They gave us a bad name. They called us dirty feet, illiterate, ignorant and finally they called us chimere,'' Civil said. ``We became a problem for them, why? We were in daily contact with the men in power.''

Reprinted from The Miami Herald of June 5, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |