| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted November 27, 2006 |

| Very Rich Are Leaving The Merely Rich Behind |

|

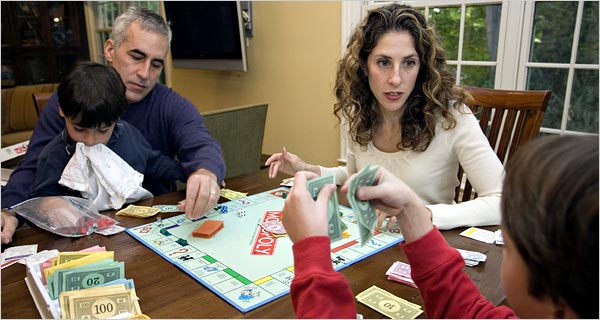

Emile Wamsteker for The New York Times |

| Robert and Denise Glassman with sons Jeremy, 8, at right, and Spencer, 5, at their home in Short Hills, N.J. |

____________ |

|

By LOUIS UCHITELLE |

A decade into the practice of medicine, still striving to become “a well regarded physician-scientist,” Robert H. Glassman concluded that he was not making enough money. So he answered an ad in the New England Journal of Medicine from a business consulting firm hiring doctors.

Such routes to great wealth were just opening up to physicians when Dr. Glassman was in school, graduating from Harvard College in 1983 and Harvard Medical School four years later. Hoping to achieve breakthroughs in curing cancer, his specialty, he plunged into research, even dreaming of a Nobel Prize, until Wall Street reordered his life.

Just how far he had come from a doctor’s traditional upper-middle-class expectations struck home at the 20th reunion of his college class. By then he was working for Merrill Lynch and soon would become a managing director of health care investment banking.

“There were doctors at the reunion — very, very smart people,” Dr. Glassman recalled in a recent interview. “They went to the top programs, they remained true to their ethics and really had very pure goals. And then they went to the 20th-year reunion and saw that somebody else who was 10 times less smart was making much more money.”

The opportunity to become abundantly rich is a recent phenomenon not only in medicine, but in a growing number of other professions and occupations. In each case, the great majority still earn fairly uniform six-figure incomes, usually less than $400,000 a year, government data show. But starting in the 1990s, a significant number began to earn much more, creating a two-tier income stratum within such occupations.

The divide has emerged as people like Dr. Glassman, who is 45, latched onto opportunities within their fields that offered significantly higher incomes. Some lawyers and bankers, for example, collect much larger fees than others in their fields for their work on business deals and cases.

Others have moved to different, higher-paying fields — from academia to Wall Street, for example — and a growing number of entrepreneurs have seen windfalls tied largely to expanding financial markets, which draw on capital from around the world. The latter phenomenon has allowed, say, the owner of a small mail-order business to sell his enterprise for tens of millions instead of the hundreds of thousands that such a sale might have brought 15 years ago.

Three decades ago, compensation among occupations differed far less than it does today. That growing difference is diverting people from some critical fields, experts say. The American Bar Foundation, a research group, has found in its surveys, for instance, that fewer law school graduates are going into public-interest law or government jobs and filling all the openings is becoming harder.

Something similar is happening in academia, where newly minted Ph.D.’s migrate from teaching or research to more lucrative fields. Similarly, many business school graduates shun careers as experts in, say, manufacturing or consumer products for much higher pay on Wall Street.

And in medicine, where some specialties now pay far more than others, young doctors often bypass the lower-paying fields. The Medical Group Management Association, for example, says the nation lacks enough doctors in family practice, where the median income last year was $161,000.

“The bigger the prize, the greater the effort that people are making to get it,” said Edward N. Wolff, a New York University economist who studies income and wealth. “That effort is draining people away from more useful work.”

What kind of work is most useful is a matter of opinion, of course, but there is no doubt that a new group of the very rich have risen today far above their merely affluent colleagues.

| Turning to Philanthrophy |

One in every 825 households earned at least $2 million last year, nearly double the percentage in 1989, adjusted for inflation, Mr. Wolff found in an analysis of government data. When it comes to wealth, one in every 325 households had a net worth of $10 million or more in 2004, the latest year for which data is available, more than four times as many as in 1989.

As some have grown enormously rich, they are turning to philanthropy in a competition that is well beyond the means of their less wealthy peers. “The ones with $100 million are setting the standard for their own circles, but no longer for me,” said Robert Frank, a Cornell University economist who described the early stages of the phenomenon in a 1995 book, “The Winner-Take-All Society,” which he co-authored.

Fighting AIDS and poverty in Africa are favorite causes, and so is financing education, particularly at one’s alma mater.

“It is astonishing how many gifts of $100 million have been made in the last year,” said Inge Reichenbach, vice president for development at Yale University, which like other schools tracks the net worth of its alumni and assiduously pursues the richest among them.

Dr. Glassman hopes to enter this circle someday. At 35, he was making $150,000 in 1996 (about $190,000 in today’s dollars) as a hematology-oncology specialist. That’s when, recently married and with virtually no savings, he made the switch that brought him to management consulting.

He won’t say just how much he earns now on Wall Street or his current net worth. But compensation experts, among them Johnson Associates, say the annual income of those in his position is easily in the seven figures and net worth often rises to more than $20 million.

“He is on his way,” said Alan Johnson, managing director of the firm, speaking of people on career tracks similar to Dr. Glassman’s. “He is destined to riches.”

Indeed, doctors have become so interested in the business side of medicine that more than 40 medical schools have added, over the last 20 years, an optional fifth year of schooling for those who want to earn an M.B.A. degree as well as an M.D. Some go directly to Wall Street or into health care management without ever practicing medicine.

“It was not our goal to create masters of the universe,” said James Aisner, a spokesman for Harvard Business School, whose joint program with the medical school started last year. “It was to train people to do useful work.”

Dr. Glassman still makes hospital rounds two or three days a month, usually on free weekends. Treating patients, he said, is “a wonderful feeling.” But he sees his present work as also a valuable aspect of medicine.

One of his tasks is to evaluate the numerous drugs that start-up companies, particularly in biotechnology, are developing. These companies often turn to firms like Merrill Lynch for an investment or to sponsor an initial public stock offering. Dr. Glassman is a critical gatekeeper in this process, evaluating, among other things, whether promising drugs live up to their claims.

What Dr. Glassman represents, along with other very rich people interviewed for this article, is the growing number of Americans who acknowledge that they have accumulated, or soon will, more than enough money to live comfortably, even luxuriously, and also enough so that their children, as adults, will then be free to pursue careers “they have a hunger for,” as Dr. Glassman put it, “and not feel a need to do something just to pay the bills.”

In an earlier Gilded Age, Andrew Carnegie argued that talented managers who accumulate great wealth were morally obligated to redistribute their wealth through philanthropy. The estate tax and the progressive income tax later took over most of that function — imposing tax rates of more than 70 percent as recently as 1980 on incomes above a certain level.

Now, with this marginal rate at half that much and the estate tax fading in importance, many of the new rich engage in the conspicuous consumption that their wealth allows. Others, while certainly not stinting on comfort, are embracing philanthropy as an alternative to a life of professional accomplishment.

Bill Gates and Warren Buffett are held up as models, certainly by Dr. Glassman. “They are going to make much greater contributions by having made money and then giving it away than most, almost all, scientists,” he said, adding that he is drawn to philanthropy as a means of achieving a meaningful legacy.

“It has to be easier than the chance of becoming a Nobel Prize winner,” he said, explaining his decision to give up research, “and I think that goes through the minds of highly educated, high performing individuals.”

As Bush administration officials see it — and conservative economists often agree — philanthropy is a better means of redistributing the nation’s wealth than higher taxes on the rich. They argue that higher marginal tax rates would discourage entrepreneurship and risk-taking. But some among the newly rich have misgivings.

Mark M. Zandi is one. He was a founder of Economy.com, a forecasting and data gathering service in West Chester, Pa. His net worth vaulted into eight figures with the company’s sale last year to Moody’s Investor Service.

“Our tax policies should be redesigned through the prism that wealth is being increasingly skewed,” Mr. Zandi said, arguing that higher taxes on the rich could help restore a sense of fairness to the system and blunt a backlash from a middle class that feels increasingly squeezed by the costs of health care, higher education, and a secure retirement. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, a principal government source of income and wealth data, does not single out the occupations and professions generating so much wealth today. But Forbes magazine offers a rough idea in its annual surveys of the richest Americans, those approaching and crossing the billion dollar mark.

Some routes are of long standing. Inheritance plays a role. So do the earnings of Wall Street investment bankers and the super incomes of sports stars and celebrities. All of these routes swell the ranks of the very rich, as they did in 1989.

But among new occupations, the winners include numerous partners in recently formed hedge funds and private equity firms that invest or acquire companies. Real estate developers and lawyers are more in evidence today among the very rich. So are dot-com entrepreneurs as well as scientists who start a company to market an invention or discovery, soon selling it for many millions. And from corporate America come many more chief executives than in the past.

Seventy-five percent of the chief executives in a sample of 100 publicly traded companies had a net worth in 2004 of more than $25 million mainly from stock and options in the companies they ran, according to a study by Carola Frydman, a finance professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management. That was up from 31 percent for the same sample in 1989, adjusted for inflation. Chief executives were not alone among corporate executives in rising to great wealth. There were similar or even greater increases in the percentage of lower-ranking executives — presidents, executive vice presidents, chief financial officers — also advancing into the $25 million-plus category.

|

Michael Nagle for The New York Times |

"If Wall Street was not there as an alternative, I would have gone into academia." |

JOHN J. MOON |

Managing director of a private equity firm, who had intended to become a teacher |

The growing use of options as a form of pay helps to explain the sharp rise in the number of very wealthy households. But so does the gradual dismantling of the progressive income tax, Ms. Frydman concluded in a recent study.

“Our simulation results suggest that, had taxes been at their low 2000 level throughout the past 60 years, chief executive compensation would have been 35 percent higher during the 1950s and 1960s,” she wrote.

| Trying Not to Live Ostentatiously |

Finally, the owners of a variety of ordinary businesses — a small chain of coffee shops or temporary help agencies, for example — manage to expand these family operations with the help of venture capital and private equity firms, eventually selling them or taking them public in a marketplace that rewards them with huge sums. John J. Moon, a managing director of Metalmark Capital, a private equity firm, explains how this process works.

“Let’s say we buy a small pizza parlor chain from an entrepreneur for $10 million,” said Mr. Moon, who at 39, is already among the very rich. “We make it more efficient, we build it from 10 stores to 100 and we sell it to Domino’s for $50 million.”

As a result, not only the entrepreneur gets rich; so do Mr. Moon and his colleagues, who make money from putting together such deals and from managing the money they raise from wealthy investors who provide much of the capital.

By his own account, Mr. Moon, like Dr. Glassman, came reluctantly to the accumulation of wealth. Having earned a Ph.D. in business economics from Harvard in 1994, he set out to be a professor of finance, landing a job at Dartmouth’s Tuck Graduate School of Business, with a starting salary in the low six figures.

To this day, teaching tugs at Mr. Moon, whose parents immigrated to the United States from South Korea. He steals enough time from Metalmark Capital to teach one course in finance each semester at Columbia University’s business school. “If Wall Street was not there as an alternative,” Mr. Moon said, “I would have gone into academia.”

Academia, of course, turned out to be no match for the job offers that came Mr. Moon’s way from several Wall Street firms. He joined Goldman Sachs, moved on to Morgan Stanley’s private equity operation in 1998 and stayed on when the unit separated from Morgan Stanley in 2004 and became Metalmark Capital.

As his income and net worth grew, the Harvard alumni association made contact and he started to give money, not just to Harvard, but to various causes. His growing charitable activities have brought him a leadership role in Harvard alumni activities, including a seat on the graduate school alumni council.

Still, Mr. Moon tries to live unostentatiously. “The trick is not to want more as your income and wealth grow,” he said. “You fly coach and then you fly first class and then it is fractional ownership of a jet and then owning a jet. I still struggle with first class. My partners make fun of me.”

His reluctance to show his wealth has a basis in his religion. “My wife and I are committed Presbyterians,” he said. “I would like to think that my faith informs my career decisions even more than financial considerations. That is not always easy because money is not unimportant.”

It has a momentum of its own. Mr. Moon and his wife, Hee-Jung, who gave up law to raise their two sons, are renovating a newly purchased Park Avenue co-op. “On an absolute scale it is lavish,” he said, “but on a relative scale, relative to my peers, it is small."

Behavior is gradually changing in the Glassman household, too. Not that the doctor and his wife, Denise, 41, seem to crave change. Nothing in his off-the-rack suits, or the cafes and nondescript restaurants that he prefers for interviews, or the family’s comparatively modest four-bedroom home in suburban Short Hills, N.J., or their two cars (an Acura S.U.V. and a Honda Accord) suggests that wealth has altered the way the family lives.

But it is opening up “choices,” as Mrs. Glassman put it. They enjoy annual ski vacations in Utah now. The Glassmans are shopping for a larger house — not as large as the family could afford, Mrs. Glassman said, but large enough to accommodate a wood-paneled study where her husband could put all his books and his diplomas and “feel that it is his own.” Right now, a glassed-in porch, without book shelves, serves as a workplace for both of them.

Starting out, Dr. Glassman’s $150,000 a year was a bit less than that of his wife, then a marketing executive with an M.B.A. from Northwestern. Their plan was for her to stop working once they had children. To build up their income, she encouraged him to set up or join a medical practice to treat patients. Dr. Glassman initially balked, but he was coming to realize that his devotion to research would not necessarily deliver a big scientific payoff.

“I wasn’t sure that I was willing to take the risk of spending many years applying for grants and working long hours for the very slim chance of winning at the roulette table and making a significant contribution to the scientific literature,” he said.

In this mood, he was drawn to the ad that McKinsey & Company, the giant consulting firm, had placed in the New England Journal of Medicine. McKinsey was increasingly working among biomedical and pharmaceutical companies and it needed more physicians on staff as consultants. Dr. Glassman, absorbed in the world of medicine, did not know what McKinsey was. His wife enlightened him. “The way she explained it, McKinsey was like a Massachusetts General Hospital for M.B.A.’s,” he said. “It was really prestigious, which I liked, and I heard that it was very intellectually charged.”

He soon joined as a consultant, earning a starting salary that was roughly the same as he was earning as a researcher — and soon $100,000 more. He stayed four years, traveling constantly and during that time the family made the move to Short Hills from rented quarters in Manhattan.

Dr. Glassman migrated to Merrill Lynch in 2001, first in private equity, which he found to be more at the forefront of innovation than consulting at McKinsey, and then gradually to investment banking, going full time there in 2004.

| Linking Security to Income |

Casey McCullar hopes to follow a similar circuit. Now 29, he joined the Marconi Corporation, a big telecommunications company, in 1999 right out of the University of Texas in Dallas, his hometown. Over the next six years he worked up to project manager at $42,000 a year, becoming quite skilled in electronic mapmaking.

A trip to India for his company introduced him to the wonders of outsourcing and the money he might make as an entrepreneur facilitating the process. As a first step, he applied to the Tuck business school at Dartmouth, got in and quit his Texas job, despite his mother’s concern that he was giving up future promotions and very good health insurance, particularly Marconi’s dental plan.

His life at Tuck soon sent him in still another direction. When he graduates next June he will probably go to work for Mercer Management Consulting, he says. Mercer recruited him at a starting salary of $150,000, including bonus. “If you had told me a couple of years ago that I would be making three times my Marconi salary, I would not have believed you,” Mr. McCullar said.

Nearly 70 percent of Tuck’s graduates go directly to consulting firms or Wall Street investment houses. He may pursue finance later, Mr. McCullar says, always keeping in mind an entrepreneurial venture that could really leverage his talent.

“When my mom talks of Marconi’s dental plan and a safe retirement,” he said, “she really means lifestyle security based on job security.”

But “for my generation,” Mr. McCullar said, “lifestyle security comes from financial independence. I’m doing what I want to do and it just so happens that is where the money is.”

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Monday, November 27, 2006

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |