| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted April 17, 2004 |

| Think Tank |

Emily Eakin |

Uncovering an Interracial Literature of Love ... and Racism |

|

Bettman/Corbis |

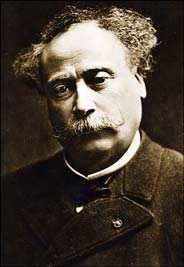

| Alexandre Dumas fils |

The word miscegenation entered America's bitter racial politics and the national lexicon by way of an ambitious hoax. On Christmas Day in 1863, an anonymous 72-page pamphlet appeared on newsstands around New York City. Titled "Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro," it had all the earmarks of a tract by radical abolitionists.

Arguing that "science has demonstrated that the intermarriage of diverse races is indispensable to a progressive humanity," it triumphantly unveiled a new vocabulary to accompany America's noble, interracial future. In addition to "miscegenation" (derived, the text explained, from the Latin words miscere, to mix, and genus, race), the neologisms included: "miscegen" ("an offspring of persons of different races"), "miscegenate" ("to mingle persons of different races") and "melaleukation" (from the Greek words melas and leukos, for black and white, and used to mean the mingling of those races).

"We must become a yellow-skinned, black-haired people — in fine, we must become miscegens if we would attain the fullest results of civilization," the pamphlet exhorted, pointing to the number of European nations composed "of many diverse bloods" that could claim extraordinary cultural achievements. Just consider the French, it suggested by way of example: "The two most brilliant writers it can boast of are the melaleukon, Dumas, and his son, a quadroon."

Applauded by prominent abolitionists and denounced in Congress, the pamphlet made miscegenation a household word. But the work turned out to be a fraud, an ultimately unsuccessful scheme by two journalists at a pro-Democratic newspaper to turn voters against Abraham Lincoln, the Republican president who freed the slaves and was up for re-election in 1864.

"You have to imagine that an 1863 audience would take this as the worst possible thing," said Werner Sollors, a professor of English and African-American studies at Harvard. "If you read it from a 21st-century point of view, a lot of it seems common sensical."

The pamphlet is just one of many startling textual artifacts Mr. Sollors included in a new book he edited, "An Anthology of Interracial Literature: Black-White Contacts in the Old World and the New." Published in February by New York University Press, the $28 anthology is the first in English devoted to work that Mr. Sollors says has typically been overlooked, an orphan literature belonging to no clear ethnic or national tradition.

Many of the selections seem likely to confound expectations. Interracial marriage was illegal in most states and in Britain for much of the last century, Mr. Sollors notes in the introduction. (Only in 1967 did the United States Supreme Court declare state bans on interracial marriage unconstitutional.) But what he calls the "absolutely paranoid version" of interracial bias appears to have been a relatively recent development.

For the ancient Greek philosopher Cleobulus, for example, interracial procreation provided a handy and benign metaphor for a riddle about day and night. And in "Parzival," a 12th-century Arthurian romance, the German writer Wolfram von Eschenbach stages an emotional battlefield encounter between the knight Parzival and his half-black half brother Feirefis. (Although having been raised apart, the brothers recognize each other in battle and put aside "hatred and wrath" for "a brotherly embrace.")

The anthology also features half a dozen Renaissance poems celebrating interracial love, among them a translation of a lyric poem written by George Herbert in Latin. It begins: "What if my face be black? O Cestus, hear!/Such colour Night brings, which yet Love holds dear." In addition Mr. Sollors has included a chapter from "Georges" (1843), a novel with a wealthy, mixed-race hero by Alexandre Dumas, himself the son of a biracial father (the "melaleukon" of the pamphlet), as well as the complete text of "Ourika," an 1823 novella told from the point of view of a black Senegalese woman who experiences racism in France, her adopted homeland. The novella, by a Frenchwoman, Claire de Duras, presents "the first fully dimensioned portrayal of a black person in European literature," Mr. Sollors writes. Enormously popular at the time, it inspired a rash of knock-offs as well as a vogue for "Ourika"-themed clothing and hairstyles.

Not surprisingly, more recent narratives with interracial themes have tended to take on a more tragic cast. Mr. Sollors's book includes stark depictions of virulent prejudice and thwarted interracial love by late-19th- and 20th-century writers both black and white, including Guy de Maupassant, Kate Chopin, Jean Toomer and Langston Hughes.

But his most exciting find, he said, was a work that ends with a happy interracial marriage: "Mulatto," an obscure play from 1840 by the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen. Not mentioned in standard bibliographies of the author and never before translated into English, the play was listed in the catalog at Harvard's rare books library, where Mr. Sollors stumbled upon it in 1990 when he searched for titles containing the Danish word for mulatto. The story of Horatio, a Shakespeare-reading mulatto whose owner, a white countess, falls in love with him and, marrying him, grants his freedom, the play was a hit with Danish audiences.

"People have always had an interest in color," Mr. Sollors pointed out. "It just didn't always have the same meaning."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, April 17, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |