NAIROBI, Kenya — David Kato knew he was a marked man.

|

Ugandan Who Spoke Up for Gays Is Beaten to Death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ASSOCIATED PRESS |

|

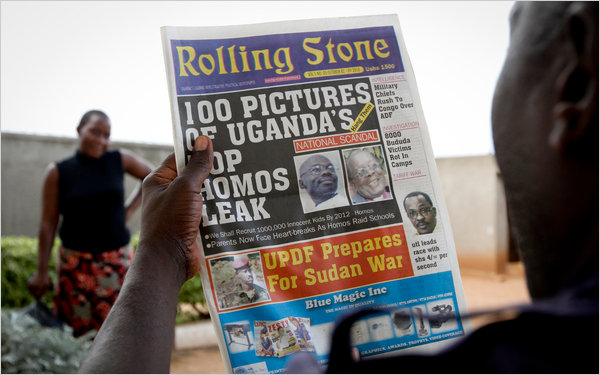

| In October 2010, Rolling Stone, a newspaper in Kampala, published photographs of gay Ugandans. Included was one of David Kato, a gay activist, who was killed on Wednesday. |

|

By JEFFREY GENTTLEMAN |

Related

-

Remembering David Kato, a Gay Ugandan and a Marked Man (January 30, 2011)

-

The Lede Blog: Before His Death, Ugandan Gay Rights Activist Explained Hostile Climate (January 27, 2011)

As the most outspoken gay rights advocate in Uganda, a country where homophobia is so severe that Parliament is considering a bill to execute gay people, Mr. Kato had received a stream of death threats, his friends said. A few months ago, a Ugandan newspaper ran an antigay diatribe with Mr. Kato’s picture on the front page under a banner urging, “Hang Them.”

On Wednesday afternoon, Mr. Kato was beaten to death with a hammer in his rough-and-tumble neighborhood. Police officials were quick to chalk up the motive to robbery, but members of the small and increasingly besieged gay community in Uganda suspect otherwise.

“David’s death is a result of the hatred planted in Uganda by U.S. evangelicals in 2009,” Val Kalende, the chairwoman of one of Uganda’s gay rights groups, said in a statement. “The Ugandan government and the so-called U.S. evangelicals must take responsibility for David’s blood.”

Ms. Kalende was referring to visits in March 2009 by a group of American evangelicals, who held rallies and workshops in Uganda discussing how to turn gay people straight, how gay men sodomized teenage boys and how “the gay movement is an evil institution” intended to “defeat the marriage-based society.”

The Americans involved said they had no intention of stoking a violent reaction. But the antigay bill was drafted shortly thereafter. Some of the Ugandan politicians and preachers who wrote it had attended those sessions and said that they had discussed the legislation with the Americans.

After growing international pressure and threats from a few European countries to cut assistance — Uganda relies on hundreds of millions of dollars of aid — Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, indicated that the bill would be scrapped.

But more than a year later, that has not happened, and the legislation remains a simmering issue in Parliament. Some political analysts say the bill could be passed in the coming months, after a general election in February that is expected to return Mr. Museveni, who has been in office for 25 years, to power.

On Thursday, Don Schmierer, one of the American evangelicals who visited Uganda in 2009, said Mr. Kato’s death was “horrible.”

“Naturally, I don’t want anyone killed, but I don’t feel I had anything to do with that,” said Mr. Schmierer, who added that in Uganda he had focused on parenting skills. He also said that he had been a target of threats himself, recently receiving more than 600 messages of hate mail related to his visit.

“I spoke to help people,” he said, “and I’m getting bludgeoned from one end to the other.”

Many Africans view homosexuality as an immoral Western import, and the continent is full of harsh homophobic laws. In northern Nigeria, gay men can face death by stoning. In Kenya, which is considered one of the more Westernized nations in Africa, gay people can be sentenced to years in prison.

But Uganda seems to be on the front lines of this battle. Conservative Christian groups that espouse antigay beliefs have made great headway in this country and wield considerable influence. Uganda’s minister of ethics and integrity, James Nsaba Buturo, who describes himself as a devout Christian, has said, “Homosexuals can forget about human rights.”

At the same time, American groups that defend gay rights have also poured money into Uganda to help the beleaguered gay community.

In October, a Ugandan newspaper called Rolling Stone (with a circulation of roughly 2,000 and no connection to the American magazine) published an article that included photos and the whereabouts of gay men and lesbians, including several well-known activists like Mr. Kato.

The paper said homosexuals were raiding schools and recruiting children, a belief that is quite widespread in Uganda and has helped drive the homophobia.

Mr. Kato and a few other activists sued the paper and won. This month, Uganda’s High Court ordered Rolling Stone to pay hundreds of dollars in damages and to cease publishing the names of people it said were gay.

But the danger remained.

“I had to move houses,” said Stosh Mugisha, a woman who is going through a transition to become a man. “People tried to stone me. It’s so scary. And it’s getting worse.”

On Thursday, Giles Muhame, Rolling Stone’s managing editor, said he did not think that Mr. Kato’s killing had anything to do with what his paper had published.

“There is no need for anxiety or for hype,” he said. “We should not overblow the death of one.”

But that one man was considered a founding father of Uganda’s nascent gay rights movement. In an interview in 2009, Mr. Kato shared his life story, how he was raised in a conservative family where “we grew up brainwashed that it was wrong to be in love with a man.”

He was a high school teacher who had graduated from some of Uganda’s best schools, and he moved to South Africa in the mid-1990s, where he came out. A few years ago, he organized what he claimed was Uganda’s first gay rights news conference in Kampala, the capital, and said he was punched in the face and cracked in the nose by police officers soon afterward.

Friends said that Mr. Kato had recently put an alarm system in his house and was killed by an acquaintance, someone who had been inside several times before and was seen by neighbors on Wednesday. Mr. Kato’s neighborhood on the outskirts of Kampala is known as a rough one, where several people have recently been beaten to death with iron bars.

Judith Nabakooba, a police spokeswoman, said Mr. Kato’s death did not appear to be a hate crime, though the investigation had just started. “It looks like theft, as some things were stolen,” Ms. Nabakooba said.

But Nikki Mawanda, a friend who was born female and lives as a man, said: “This is a clear signal. You don’t know who’s going to do it to you.”

Mr. Kato was in his mid-40s, his friends said. He was a fast talker, fidgety, bespectacled, slightly built and constantly checking over his shoulder, even in the envelope of darkness of an empty lot near a disco, where he was interviewed in 2009.

He said then that he wanted to be a “good human rights defender, not a dead one, but an alive one.”