| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted December 14, 2006 |

Trove of Black History Gathered Over Lifetime Seeks a Museum |

|

Marissa Roth for The New York Times |

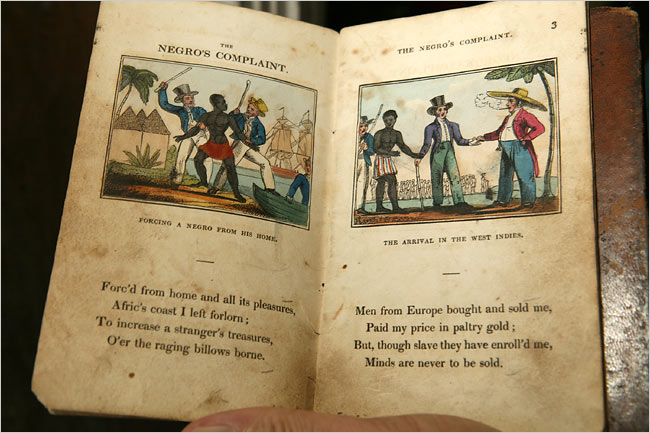

| An early-19th-century edition of "The Negro's Complainr" is among the collection's thousands of rare books. |

_________________________ |

|

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER |

|

LOS ANGELES, Dec. 13 — Behind the dusty stools and the old towels, under the broken telephones and the picture frames, amid the spider webs, sits one of the country’s most important collections of artifacts devoted to the history of African-Americans.

Painstakingly collected over a lifetime by Mayme Agnew Clayton — a retired university librarian who died in October at 83 and whose interest in African-American history consumed her for most of her adult life — the massive collection of books, films, documents and other precious pieces of America’s past has remained essentially hidden for decades, most of it piled from floor to ceiling in a ramshackle garage behind Ms. Clayton’s home in the West Adams district of Los Angeles.

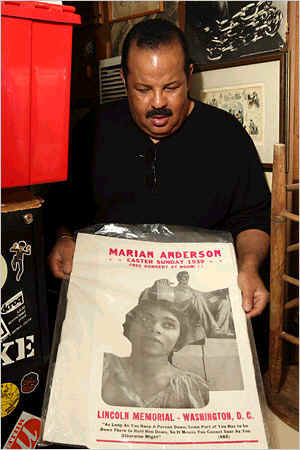

Only now is her son Avery Clayton close to forming a museum and research institute that would bring her collection out of the garage and into public view. Just days before Ms. Clayton died, he rented a former courthouse in nearby Culver City for $1 a year to become the treasures’ home, leaving him to scrape together $565,000 to move the thousands of items and put them on display for the first year. “There is no doubt that this is one of the most important collections in the United States for African-American materials,” said Sara S. Hodson, curator of literary manuscripts for the Huntington Library in San Marino, one of the country’s largest collections of rare books and manuscripts. “It is a tremendous resource for all Americans, but especially African-Americans, whose history has largely been neglected.”

There are first editions by Langston Hughes and nearly every other writer from the Harlem Renaissance, many of them signed; a rare biography of the architect Paul R. Williams; and the oeuvre of the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. There is an edition of “The Negro’s Complaint,” a poem complete with hand-painted illustrations; books by and about every notable American of African descent from George Washington Carver to Bill Cosby; and thousands more items concerning those whose names were lost or never known.

The roughly 30,000 rare and out-of-print books written by and about blacks in Ms. Clayton’s collection have never been fully archived.

There is also what Mr. Clayton calls the world’s largest collection of 16-mm films made by blacks; 75,000 photographs; 9,500 sound recordings; and tens of thousands of documents, manuscripts and correspondence: a treasure trove that Ms. Clayton assembled piece by piece, on her modest salary, scouring used bookstores, garage sales, antique shops and pretty much any place where she could find books and memorabilia related to the African-American experience.

The premier collection devoted to black literature and artifacts is the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Other major collections include the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History at the Chicago Public Library, and those of Howard University, Temple University and the University of Arkansas.

|

| Amassing a lifetime of treasures to share: Mayme Agnew Clayton. |

Ms. Clayton’s collection is distinguished by its breadth and depth of materials, scholars say, including the films, the handwritten slave documents and the staggering assortment of ephemera, and is unmatched on the West Coast. “A collection like this is, in my mind, priceless,” said Philip J. Merrill, an expert on African-American memorabilia.

Mr. Clayton recalled his mother’s longing — and inability — to find a home for her collection, where it could be used by everyone from esteemed scholars to black teenagers who have yet to hear of W. E. B. Du Bois. “Culture is the measure of a civilization,” said Mr. Clayton, who left his job as an art teacher to shepherd his mother’s collection. “Without evidence of a culture, there is no proof that a people exists.”

For now, the future Mayme E. Clayton Library and Cultural Center houses a jail cell (which may one day store sensitive materials), three courtrooms (the one with the red leather seats will be a theater) and a large portrait that Mr. Clayton painted of his mother.

But if all goes well, in 2008 it will become a research center, perhaps even a repository for other large collections of African-American history that, like his mother’s, are “sitting in boxes in the basements of homes and church libraries, waiting for a flood,” Mr. Clayton said.

The dispersion of important African-American cultural materials has long vexed researchers. “The older materials have always been collected out of a labor of love by someone who had the foresight to realize that researchers would find it valuable,” said Patricia A. Turner, a professor of African-American studies at the University of California, Davis. Putting such works together “will be very important for the scholarly community.”

Ms. Clayton’s interest in literature and black history was sparked during her childhood in Van Buren, Ark. Her father, a black merchant, wanted his children “exposed to black people of accomplishment,” Mr. Clayton said. Her father once took the family to visit Mary McLeod Bethune in Little Rock.

“I always had a desire to want to know more about my people,” Ms. Clayton said in a 2005 interview with the HistoryMakers, a video oral-history archive. “I would hear about another person, so I would go and try to find some books about that one. And it just snowballed.”

Ms. Clayton came to New York in her 20s, met Andrew Lee Clayton, whom she married in 1946, and soon moved to California to a tiny bungalow in historic West Adams where she started a family.

Her collecting grew from her work as a librarian, first at the University of Southern California and later at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she began to build an African-American collection.

In 1969 she helped establish the university’s African-American Studies Center Library, and began to buy out-of-print works by authors from the Harlem Renaissance.

Around that time, Ms. Clayton invested in a bookstore. When the principal owner squandered their profits on the horses, Mr. Clayton said, his mother agreed to take her partner’s collection of black-oriented books rather than take him to court.

Her business acumen became well known in the field. “I distinctly remember trading four items I had, which included a signed poem by Langston Hughes, for one book,” said Randall K. Burkett, the curator of African-American collections at Emory University. “Let’s just say she did very well.”

|

Marissa Roth for The New York Times |

| Mayme Agnew Clayton's son Avery Clayton, above, is establishing a museum to house the vast archive assembled by his mother over decades. |

Ms. Clayton, an avid golfer, traveled for her sport, trolling for rare finds wherever she went. Soon, dealers around the country learned of her interest, and began to call her when black books emerged.

The centerpiece of the collection is a signed copy of Phillis Wheatley’s “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” from 1773. First published by an American of African descent, the book was acquired for $600 from a New York dealer in 1973. In 2002 it was appraised at $30,000.

The books and others items Ms. Clayton amassed cost her hundreds of thousands of dollars over the years, her son said, money she got through scrimping, selling off books occasionally and living modestly.

Mr. Clayton, one of Ms. Clayton’s three sons, dreams of housing his mother’s collection in a 40,000-square-foot hilltop cultural center with an atrium garden, performance space and archived research center.

“She always wanted something grand,” he said. He estimates it would cost $7 million to operate the center for three years. So far he has raised $15,000 and he said he was working with his congresswoman for a $150,000 appropriation.

For now he just wants the collection out of her garage — the films and some other items are in storage — and into the former courthouse, where the world can see it.

“One of the things that culture does is that it works like a family,” Mr. Clayton said. “If you know you come from a good family, it enables you to go out into the world, no matter what happens to you, and do O.K. It is the same thing with culture: If you know you come from a great people, it gives you that same feeling.”

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Company, National, of December 14, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |