| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted January 11, 2010 |

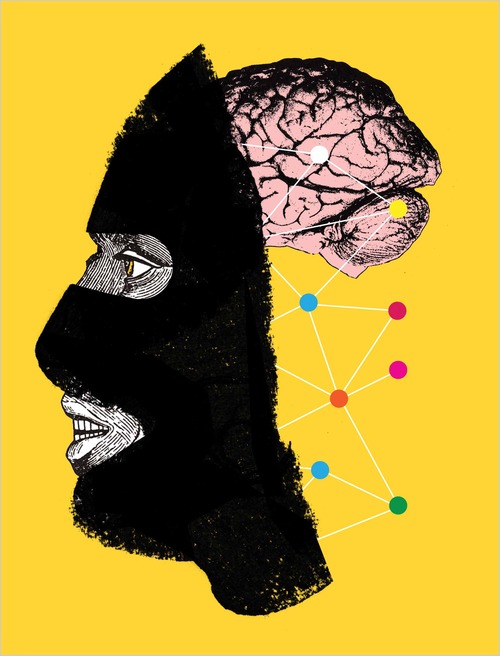

| The Terrorist Mind: An Update |

| Research is expanding rapidly. And so is the |

| thinking on the path that leads to killing and |

| martyrdom. It's not just about religion. |

|

By SARAH KERSHAW |

|

|

MATT DORFMAN |

|

|

| IDEALISTS, RESPONDENTS, LOST SOULS, REVOLUTIONARIES, WANDERERS, CRIMINALS, CONVERTS, COMPLIANTS. |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |