| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted May 24, 2007 |

| The Saga of 'Toto' Constant |

By SEWELL CHAN |

A Brooklyn judge's decision yesterday to hold Emmanuel Constant a onetime paramilitary leader and C.I.A. informer for further jail time on grand larceny charges underscores the sad and bizarre aspects of a complex legal case that spans Haiti and the United States and has caught the attention of human and civil rights advocates in both countries.

|

The New York Times |

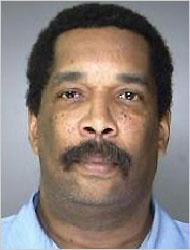

| Emmanuel 'Toto' Constant |

The paradox is this: In the 1990s, when Mr. Constant was living in Queens, the United States declined to honor an extradition request from Haiti, where Mr. Constant faces charges of brutalizing and killing supporters of the onetime president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Now, 10 years later, with Mr. Constant having pleaded guilty to charges of mortgage fraud, the United States wants to deport him but Haiti's justice system is in such tatters that it is unlikely he would stand trial if sent back.

The son of an army commander (who served under the dictator François Duvalier) and nephew of a bishop (also named Emmanuel Constant), Mr. Constant, known as Toto, was co-leader of the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, known by its French acronym, Fraph. The right-wing organization emerged in 1993 to suppress domestic support for Haiti's exiled president, Mr. Aristide.

Mr. Constant, a former United Nations diplomat, told The Times in 1994 that he had aspired to become president.is one of my goals getting there, Mr. Constant said at the time. What I have started I want to finish.

| Haiti in Turmoil |

Mr. Aristide, a Roman Catholic priest, had become president of Haiti in 1991, only to be deposed months later in a military coup. In October 1994, Mr. Aristide was restored to power, with the help of the United States and the international community. With American troops in the streets of Port-au-Prince, Mr. Constant insisted that Fraph was a political party, not a paramilitary group. The group agreed to lay down its arms.

At a news conference arranged by the United States Embassy, Mr. Constant called on Haitians to put down their tires, their stones, their guns. Then it was revealed that Mr. Constant had been a paid informer of the C.I.A. for two years and that the payments had continued even though Mr. Constant played a leading role in derailing, for a time, the Clinton administration's policy on Haiti. (While on the C.I.A. payroll, Mr. Constant had organized a violent protest in 1993 that prevented the docking of a Navy ship dispatched to Haiti to help prepare for Mr. Aristide's return.)

To the outrage of many ordinary Haitians, the American troops refused to detain Mr. Constant, saying that he was outside the scope of their mission. When a magistrate summoned Mr. Constant and his deputy, Jodel Champlain, to appear, they simply ignored the order and went underground.

In February 1995, it emerged that Mr. Constant had been granted a tourist visa to enter the United States and had disappeared from sight. Many Haitians are understandably suspicious, The Times said in an editorial. They believe that as a former paid informer for the Central Intelligence Agency, Mr. Constant has been given safe haven in the United States, or at least allowed to slip conveniently into obscurity here.

| A New Life in Queens |

That brings us to a white stucco house in Laurelton, Queens, where Mr. Constant was found hiding in May 1995, and promptly arrested. In September 1995, a federal immigration judge signed an order to deport him, but his lawyers appealed. In December 1995, in a jailhouse interview shown on 60 Minutes, Mr. Constant confirmed that he had been a paid C.I.A. informer from 1991 to 1994.

In June 1996, in an apparent deal with the Clinton administration, Mr. Constant was released. He agreed to drop a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the statute under which he was being held. Officials described the decision not to deport him as extremely unusual and made primarily for political reasons, not legal ones. A Times editorial said, The United States has set back the cause of democracy and justice in Haiti by freeing Emmanuel Constant from an American jail and postponing deportation proceedings against him.

The controversy dragged on. In October 1996, Haitian authorities said they had foiled a coup attempt by former soldiers who were arrested at a home owned by Mr. Constant. The same month, a C.I.A. report from 1993 surfaced showing that Mr. Constant had plotted the assassination of Haiti's justice minister.

By 1998, after American authorities agreed to let Mr. Constant live and work in New York temporarily, The Times reported that serious divisions had emerged within the city's Haitian community. Some Haitians in New York are now suggesting that Haiti is racked by too many problems, and question whether its fragile legal system could prosecute such a high-profile case, The Times reported.

Mr. Constant lived and worked openly. He has taken a job as a real estate broker, selling houses in Cambria Heights, the heart of the Haitian-American neighborhood in Queens, The Times reported on Aug. 12, 2000. He has been seen greeting friends with a hug and taking cigarette breaks on Linden Boulevard. And last week, after watching a discussion on public access television about a rally against him planned for today, he called the station and asked to be interviewed.

In November 2000, Mr. Constant and 15 others were convicted in absentia of a massacre of slum dwellers in the seaside shanty town of Raboteau in April 1994. He was sentenced to life in prison. Mr. Aristide again demanded Mr. Constant's extradition, to no avail.

| New Charges |

Fast forward to last July, when Mr. Constant was arrested and charged, with five others, of taking part in a mortgage fraud ring. According to the state attorney general's office, they defrauded banks out of more than $1 million in loans by using straw home buyers and inflated appraisals.

Mr. Constant has now served about 10 months of a one-to-three-year negotiated sentence for mortgage fraud. Prosecutors had agreed to a concurrent sentence of one to three years for similar charges in Brooklyn. At a hearing last week on the Brooklyn charges, lawyers for the federal Department of Homeland Security argued that Mr. Constant should be sentenced to time served, which would speed his deportation to face justice in Haiti. (The federal lawyers submitted this letter [pdf] to Justice Abraham G. Gerges.).

But a lawyer for the Center for Constitutional Rights, an advocacy group, argued that the prison and court systems in Haiti were inadequate for proper handling of the case. (The center outlined its position in a letter and memo [pdf] to the judge.) As Michael Brick reported today, the lawyer, Jennifer M. Green, persuaded the judge to order [pdf] that Mr. Constant serve his full sentence, giving Haiti's justice system time to stabilize.

In a phone interview, Marie P. Pereira, Mr. Constant's lawyer in the Brooklyn case, said that in Mr. Constant's view, he never ordered the murder of anyone, he never ordered rapes of anyone, he never ordered any of those things that took place. The atrocities in Haiti were not directed by him. He had nothing to do with it. He never directed anyone to engage in crimes against humanity.

(Ms. Pereira noted that she was only representing Mr. Constant in the Brooklyn fraud case and did not know whether he was responsible for any crimes in Haiti.)

According to Ms. Pereira, a Haitian official told the Brooklyn court that the Haitian justice system is in such disarray that the prisoners practically have the keys to the jail, and added, If he goes back to Haiti, he'll walk.

Nonetheless, Ms. Pereira said that has nothing to do with Mr. Constant's crimes in the United States. She said that Justice Gerges caved in to media pressure. She added: The judge made me and the state attorney general a promise, and he broke that promise, based on pressure from the media. His decision violates the whole premise of the plea-bargain.

Paradoxically, Mr. Constant has said he is willing to go back to Haiti even while predicting that he might be killed there after stepping off the plane. Ms. Pereira said the Haitian and American cases have to be treated separately. If in fact he committed those crimes, he should face a Haitian court, but he shouldn't be denied a plea deal on a crime in the United States based on allegations in Haiti.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, New York Region, of Wednesday, May 23, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |