| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted November 9, 2003 |

| The Organizer of the Civil Rights Movement |

| _______________ |

| By MICHAEL ANDERSON |

Bayard Rustin became famous for working behind the scenes. This paradox of his celebrity was, to a large degree, inherent in the role he chose to play in the history of his time. From the end of the Great Depression to his death in 1987, at the age of 75, Rustin was the ''master strategist of social change,'' as the historian John D'Emilio writes in his biography, ''Lost Prophet.'' The tactics of public protest that became familiar in the 1960's -- marches on Washington, Freedom Rides, sit-ins, passive resistance, civil disobedience -- were pioneered and refined by Rustin two decades earlier. Indeed, through his decisive influence on Martin Luther King Jr., whom he instructed in the philosophy and tactics of Gandhian nonviolence, Rustin created the model for the social movements of post-World War II America -- civil rights, antiwar, gay liberation, feminist. ''He resurrected mass peaceful protest from the graveyard in which cold war anti-Communism had buried it,'' D'Emilio writes, ''and made it once again a vibrant expression of citizen rights in a free society.''

|

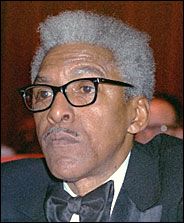

The Associated Press |

| Bayard Rustin, the civil rights activit, pictured in 1970. |

On four continents, he was esteemed for his mastery of nuts and bolts: ''precisely the number of toilets that would be needed . . . how many doctors, how many first-aid stations, what people should bring with them to eat in their lunches.'' Rustin played major roles in two defining social protests: the Aldermaston march in England in 1958, in which 10,000 people demonstrated against nuclear weapons, and, most famously, the March on Washington in 1963, in which a quarter-million people (more than double the anticipated turn-out and including fully 1 percent of the country's black population) turned out, evidence of a national consensus in support of black rights. The result of eight frantic and exhilarating weeks of work, in which, as D'Emilio writes, Rustin ''had to build an organization out of nothing,'' the March on Washington epitomized why Newsweek called him ''a genius at organization.''

Characteristically, however, in the immediate aftermath of the march, he was already looking ahead. He had been ''aiming for more than individual resistance,'' as D'Emilio writes. ''He wanted to stimulate a movement.'' As he wrote in one of the pieces collected in ''Time on Two Crosses,'' the March on Washington was ''the termination of the mass protest period -- during which Negroes had destroyed the Jim Crow institutions in the South -- and the inauguration of an era of massive action at the ballot box designed to bring about new economic programs.'' Pointing out that the theme of the march had been ''Jobs and Freedom,'' he declared that ''the civil rights movement will be advanced only to the degree that social and economic welfare gets to be inextricably entangled with civil rights.''

Such emphasis made Rustin almost unique among the major figures of the civil rights movement; along with an appeal to morality, he had an economics of equality. Perhaps that is why he had such extraordinary perceptiveness concerning what directions the movement should take as the struggle moved north in the latter half of the 60's. In the South, ''no profound analysis, no overriding social theory was needed in order both to locate and understand the injustices that were to be combated,'' he wrote. ''All that was demanded of one was sufficient courage to demonstrate against them.'' (Rustin spoke with the authority of experience. In 1942, his defiance of Jim Crow seating on a bus near Nashville earned him a beating in the police station, which he endured with such Gandhian sang-froid that the frustrated police chief cried, ''Nigger, you're supposed to be scared when you come in here!'' Five years later, following a Supreme Court decision declaring segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional, Rustin was part of the first Freedom Ride, for which he served 22 days on a North Carolina chain gang.)

However, Rustin continued, ''the evils in the North are not easy to understand and fight against.'' These, Rustin emphasized, ''are problems which, while conditioned by Jim Crow, do not vanish upon its demise. They are more deeply rooted in our socioeconomic order; they are the result of the total society's failure to meet not only the Negro's needs but human needs generally.'' In Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, Rustin perceived the promise of social democracy in the United States; the civil rights coalition -- ''Negroes, trade unionists, liberals and religious groups'' -- could act, in a union of enlightened self-interest, to achieve what Rustin called ''the Freedom Budget,'' in effect a domestic Marshall Plan that would devote $185 billion to job creation.

This program (and vision) represented the summation of Rustin's wide-ranging career up to the mid-60's. When he arrived in Depression-era Harlem from his native West Chester, Pa., in 1937, the 25-year-old Rustin ''was an eager young explorer of the American left,'' D'Emilio writes, briefly engaged with the Communist Party before its cynical exploitation of the race issue disillusioned him (as it did other young black intellectuals like Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison). His thinking was molded by his association with A. J. Muste, the militant pacifist (''we must resolutely carry our political task to the end''), and A. Philip Randolph, the socialist labor leader; Rustin was a youth leader with Randolph's March on Washington Movement of 1941, whose threatened demonstration forced President Franklin Roosevelt to ban racial discrimination in federal and defense hiring and to establish a Fair Employment Practices Committee.

A quarter of a century's worth of work with pacifist organizations confirmed Rustin's belief in direct action -- that principle had to be found in practice, a belief with immense social repercussions, as Gandhi had demonstrated in India. (His greatest pupil in this regard was, of course, King, for whom Rustin was an adviser beginning with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956: ''Rustin was as responsible as anyone else for the insinuation of nonviolence into the very heart of what became the most powerful social movement in 20th-century America,'' D'Emilio writes.) From Randolph, his constant protector in the deadly turf wars among civil rights organizations (D'Emilio gives superb detail on this surprisingly understudied topic), Rustin learned the importance of attention to bread-and-butter issues and of the proper use of protest. ''A demonstration should have an immediately achievable target,'' as Rustin put it. He came to see that the goal of protest, social reform, necessitated political participation -- itself the mark of inclusion in a society. ''The issue is which coalition to join and how to make it responsive to your program,'' he wrote. ''Necessarily there will be compromise. But the difference between expediency and morality in politics is the difference between selling out a principle and making smaller concessions to win larger ones. The leader who shrinks from this task reveals not his purity but his lack of political sense.''

And so, after his great triumph in 1963, Rustin proposed transforming the civil rights movement ''from a protest movement into a full-fledged social movement.'' As Robert Penn Warren noted in 1965, in his book ''Who Speaks for the Negro?,'' Rustin ''had anticipated the direction in which lately more and more of the Negro leaders have been moving''; King, it will be remembered, was planning his Poor People's Campaign when he was assassinated in 1968.

But Rustin discovered that the momentum of social protest is hard to redirect. Three months after the March on Washington, he told the youthful members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee -- who constituted, as D'Emilio says, ''the most courageous group of activists in the country'' -- ''The ability to go to jail should not be substituted for a social reform program.'' Their response? ''SNCC had to work on discrimination and not worry about the broader economic issues.''

Moreover, in pinning his hopes on Johnson, Rustin -- oddly for a lifelong peace activist -- did not foresee how Vietnam would subvert the Great Society. He recognized that ''a perilous polarization is taking place in our society,'' caused by the war and the generation gap. ''But generations come and go and so do foreign policies. The issue of race, however, has been with us since our earliest beginnings as a nation.'' Such statements caused him to become ''a target of intense ire'' from white radicals, who, as D'Emilio shows, were abandoning the civil rights movement long before Stokely Carmichael uttered the fateful words ''black power.'' For the rest of his life, despite his continued activism, Rustin witnessed the increasing decadence of public protest in the United States -- reduced to symbolic gestures like colored ribbons, the narcissism of identity politics and that most fatuous of slogans, ''the personal is political.'' As he wrote, ''People who seek social change will, in the absence of real substantive victories, often seize upon stylistic substitutes.''

This trivialization of the political threatens to engulf Rustin himself; in the current fashion, he is studied less as an activist exemplar than as a putative victim. The editors of ''Time on Two Crosses'' -- Devon W. Carbado, a professor of law and African-American studies at U.C.L.A., and Donald Weise, an editor of ''Black Like Us: A Century of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual African-American Fiction'' -- write that ''Rustin remained an outsider in black civil rights circles for much of his life. He was openly gay.'' D'Emilio -- who teaches history and gender and women's studies at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and is the author of the groundbreaking ''Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970'' -- several times refers to ''the stigma of his sexuality'' and declares that Rustin's homosexuality ''severely restricted the public roles he was allowed to assume.'' But his own scholarship shows quite the opposite.

Rustin was remarkably open for a pre-Stonewall gay man. A lover from his youth told D'Emilio: ''I never had any sense at all that Bayard felt any shame or guilt about his homosexuality. And that was rare in those days. Rare.'' The shame came in Pasadena in 1953, when Rustin was convicted on a morals charge, the result of improvident cruising. The incident was devastating personally, caused a rupture with his mentor, Muste, and left Rustin vulnerable to scandal. Always publicity-conscious, the heads of the major civil rights organizations (Randolph always excepted) camouflaged their turf jealousy with a veiled prejudice. However, it does not minimize recognition of the venomous bigotry directed at gay people to note that Rustin's civil rights activism was virtually unimpaired by his homosexuality or (remarkably) by his arrest record -- no small matter in a movement predicated on moralism.

Indeed, D'Emilio documents that the major civil rights leaders, as well as the establishment press, rallied in support of Rustin when the Southern demagogue Strom Thurmond attempted to smear him as a pervert (and a Commie) on the eve of the March on Washington. And though it is King's ''I Have a Dream'' speech that has become the emblem of the march, when Life magazine published its report, the cover bore a photograph of Bayard Rustin. D'Emilio, whose scholarly conscientiousness coexists with his tendentiousness, points out that after the march, Rustin was ''always in the papers. . . . Reporters sought his views on any and all civil rights matters.'' (The New York Herald Tribune called him the ''Socrates of the Civil Rights Movement.'')

''I don't think that even a social movement can be based on past sins'' -- do Rustin's words now sound odd for a protest leader? Such is the distance from the movement, from principled heroism to licensed resentment, from social justice (the very term sounds anachronistic) to the spoils system of preferences, from celebrating a remarkable man to fabricating a victim. Rustin probably would not have been much surprised; certainly he would not have been discouraged. ''God does not require us to achieve any of the good tasks that humanity must pursue,'' he once said. ''What God requires of us is that we not stop trying.'' Michael Anderson is an editor at the Book Review. He is writing a biography of the playwright Lorraine Hansberry.

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Books, of November 9, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |