| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted September 30, 2007 |

| The Oldest Inmate Is Ready to Confess. Sort Of. |

|

||

| Charles Friedgood, 88, has been in prison three decades. He says some events in his life were unnecessary. "If you don't want to be with a woman anymore, you divorce. You know, you don't have to resort to murder." |

By SAM ROBERTS |

II could have been the perfect crime. A wealthy heart surgeon from Long Island injected his 48-year-old invalid wife, the mother of their six children, with a lethal dose of a painkiller. The death certificate recorded the cause as a stroke.

But the police were suspicious from the start because the surgeon had signed the certificate himself and immediately shipped the body out of state for burial. Five weeks later, he was arrested at Kennedy International Airport trying to leave the country with more than $450,000 of his wife’s cash, negotiable bonds and jewelry.

In 1977, he was convicted of second-degree murder after one of a turbulent decade’s most celebrated trials. He was sentenced to 25 years to life. He never testified, but was imprisoned still protesting his innocence.

Fast forward 30 years. Today, the surgeon, Charles E. Friedgood, is the oldest inmate in a New York State prison. Suffering from a catalog of physical ailments and an emotion resembling remorse, he is seeking parole again next week. He is ready to admit that he did “it,” depending on how you define “it.”

“You look back, you know, it’s you can’t believe how sometimes things happen that you did that it was completely unnecessary,” Dr. Friedgood said in a recent interview from prison. “If you don’t want to be with a woman anymore, you divorce. You know, you don’t have to resort to murder. So 32 years later, I begin to realize how stupid you can do things.”

|

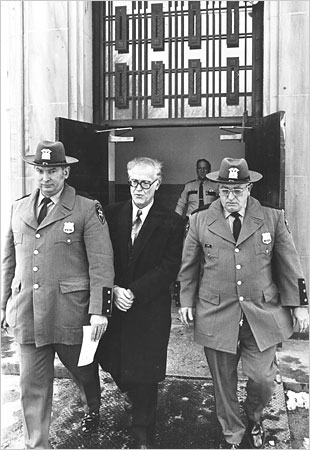

Robert Wilker/The New York Times |

| Charles Friedgoo leaving the courthouse in Mineota, N.Y. in January 1977 after being sentenced in his wife's murder. |

On Wednesday, Dr. Friedgood will mark his 89th birthday in Woodbourne Correctional Facility, a Gothic red-brick medium-security prison modeled after a monastery, in the foothills of the Catskills.

Although he has terminal cancer and has undergone numerous operations, including a colostomy, at state expense, he has been rejected for parole four times since serving his minimum sentence. Critics say the rejections were a result of a blanket no-release policy by the Pataki administration for inmates convicted of violent felonies.

In 2003, after the State Parole Board concluded that his offense “represents a propensity for extreme violence,” a state appeals court ridiculed that reasoning as “so irrational under the circumstances as to border on impropriety.” Two years later, the board denied parole again, because, it concluded, releasing Dr. Friedgood “would so deprecate the seriousness of this crime as to undermine respect for the law.”

A newly constituted Parole Board is scheduled to convene at Woodbourne next week to hear his latest request. Among those who have supported his parole are several of Dr. Friedgood’s children — one of his daughters, a lawyer, is helping on his case — and the former assistant district attorney who investigated and prosecuted the case.

“While it was a horrible crime and a terrible tragedy for the family, I think at 89 it’s time for him to be released,” the former prosecutor, Stephen Scaring, said. “He’s pretty much wasted his entire life. It’s just a matter of compassion.”

Dr. Friedgood, who practiced in Brooklyn and lived in an 18-room mansion in Great Neck, on Long Island, was convicted of injecting his wife, Sophie, with an overdose — five syringes — of the pain reliever Demerol in 1975. Mrs. Friedgood had suffered a stroke years earlier and had been in pain and poor health.

“I thought it was terribly arrogant that he would sign the death certificate and ship the body out,” said Mr. Scaring, the former chief of the homicide bureau in the Nassau County district attorney’s office.

The investigation determined that Dr. Friedgood had a mistress, a Danish nurse who cared for Mrs. Friedgood and with whom he fathered two children, and that he had looted his wife’s estate. He was arrested, prosecutors said, as he prepared to flee to Europe and join his paramour.

Dr. Friedgood insisted that he merely intended to deposit the funds in Britain to shield them from potential claims by the United States government, that he had a return ticket to New York and that he had operations scheduled the next day. (To which Ileana Rodriguez, a parole commissioner, responded: “You had just killed your wife, sir. What is the grander sin, killing your wife or leaving patients waiting in a scheduled clinic?”)

“Frankly,” Mr. Scaring remembered, “we had insufficient evidence to get an autopsy. We were pretty much winging it, but we called his bluff, and he fell for it. He could have walked on this thing. If he had kept his mouth shut and answered no questions he never would have been prosecuted. He believed he could talk his way out of everything. Instead, he talked his way into it.”

Dr. Friedgood was asked during the prison interview whether in his heart of hearts he had hoped the overdose would kill her.

“No,” he replied, “I was glad that she went to sleep and she wasn’t hollering at me anymore — ‘Do this, do that.’”

But might he have believed, even subconsciously, that his life would be better if she could never holler at him again?

“Like you say,” Dr. Friedgood replied after a deep sigh, “maybe subconsciously.”

At Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, where he had been imprisoned before being transferred to Woodbourne, he became an acolyte of Rabbi Irving Koslowe, the prison’s Jewish chaplain who was best known for escorting Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair. Dr. Friedgood became an Orthodox Jew, although he has identified only five practicing Jews among Woodbourne’s nearly 800 inmates, half the number required for a minyan, or quorum, under Jewish law.

Dr. Friedgood is representative of another group that is growing in the nation’s prisons. He is one of more than 700 inmates in New York State’s prisons, about 1.2 percent of the population, who are 65 or older, a number that has been growing because of longer sentences and fewer paroles. Advocates of alternatives to incarceration estimate that older inmates who require medical care cost two or three times more than the $32,000 a year that the state spends, on average, for each of its inmates.

“Certainly, from a safety standpoint, there is little reason to hold someone like Friedgood in jail,” said Jonathan Turley, a law professor at George Washington University and founder of the Project for Older Prisoners, which selectively advocates for their release. “The only rationale is pure retribution.”

Dr. Friedgood is a plaintiff in a pending class-action suit against the state that argues that the Parole Board, under Gov. George E. Pataki, reflexively rejected requests for release without adequately weighing inmates’ records in prison, whether their crimes were an aberration, or the likelihood they would commit them again.

Dr. Friedgood said he had reconciled with his children (he also has 20 grandchildren and 4 great-grandchildren) and that all 6 visited him in prison last year.

“Thank God they didn’t end up like their father,” he said.

As a doctor? “No, a prisoner.”

One of his lawyers, his daughter Esther A. Zaretski, said of her father: “Did he do it? That I don’t know. But he served his sentence. Under New York law, he’s entitled to be paroled.”

Not everyone agrees, including Dr. Friedgood’s brother-in-law, Sidney Klemow of Philadelphia. “I knew he was guilty the minute it happened,” Mr. Klemow, an 84-year-old retired shoe manufacturer, said.

If he is released, Dr. Friedgood said that a Veterans Affairs hospital has agreed to admit him. His license to practice medicine was revoked in 1980.

In a 90-minute prison interview not far from his first-floor cell, Dr. Friedgood was repeatedly asked whether he intended to kill his wife when he administered the Demerol.

“She was suffering, always complaining that she couldn’t play golf like she used to, and she was lame on one side — one arm and one leg,” he said. “And she became a heavy drinker and always complaining of pain and pain. And that was a sad situation.”

Noting that his wife had become “very belligerent with the children,” he said, “She was always asking for more injections, and I gave her an overdose.” Knowing what it would do?

“I figured with her tolerance, it wouldn’t be lethal,” he said. “But evidently it was.”

He didn’t really mean to kill her?

“No.”

But hadn’t he admitted his guilt to the Parole Board?

“You want to get out of here, you don’t want to die in prison, so you try to appeal to their mercy and forgiveness,” Dr. Friedgood replied.

“If you go to the Parole Board and you say you’re innocent, then they don’t take your hearing,” he added. “You have to go back to court. So if the only way you can get out is you have to admit you’re guilty and show remorse and repent and then they’ll — they might release you.”

Then what is he remorseful about?

“That I didn’t take better care of her and that I should have watched — been more diligent with the injections and that,” he said. “And I saw how she was deteriorating, drinking, and I didn’t stop it.”

Dr. Friedgood said that he was not glad that she had died.

“But I felt, you know, sometimes I used to say when a person was in terminal malignancy and suffering, sometimes it’s better you die and you not suffer so much,” he said.

Again, he was asked whether his role was not merely as a passive angel of mercy, but as a cold-blooded killer.

“Well, you see, it’s a thing that you try to feel that you’re not as bad as it appears,” Dr. Friedgood said. “And I really, I know that I’m guilty and I have to admit it and I can’t alibi, you know, bring in all the other extenuating circumstances. But I realize now that, sure, I was wrong. It was my fault. I have no one else to blame. I did a terrible thing.

“And that’s why I’m happy that I was able to survive in the prison these 30 years and do some good to make up for the bad.”

Invoking the Hebrew word for good deeds, he recalled his teaching and tutoring of other inmates, the fact that he saved the life of a guard who was having a heart attack and an inmate who was choking. He said that he hoped to continue good works outside prison, and that, on the cosmic balance sheet of his God, they will earn him a place in the afterlife. “You hope and pray that the mitzvahs will overbalance your heinous crime,” he said, “and you’ll be forgiven.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York York Times, New York Region, of Sunday, September 30, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |