| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted May 14, 2007 |

|

Lutz Widmaier |

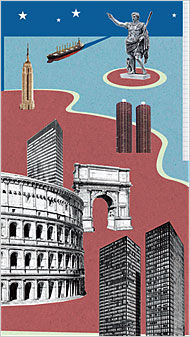

| The Empire in the Mirror | |

| ______________________________________ | |

| Cullen Murphy examines parallels between the | |

| United States today and the world of ancient Rome. | |

| ARE WE ROME? | |

| The Fall of an Empire and the Fate of America. | |

| By Cullen Murphy. | |

| 262 pp. Houghton Mifflin Company. $$24 | |

| By WALTER ISAACSON |

THE only sure thing that can be said about the past is that anyone who can remember Santayana’s maxim is condemned to repeat it. As a result, the danger of not understanding the lessons of history is matched by the danger of using simplistic historical analogies. Those who have learned the lessons of Munich square off against those who have learned the lessons of Vietnam, and then they both invoke the bread-and-circus days of the overstretched Roman empire in an attempt to sound even more subtle and profound.

In his provocative and lively “Are We Rome?” Cullen Murphy provides these requisite caveats as he engages in a serious effort to draw lessons from a comparison of America’s situation today with that of imperial Rome. Founded, according to tradition, as a farming village in 753 B.C., Rome enjoyed 12 centuries of rise and fall before the barbarians began overwhelming the gates in the fifth century. During that time it became a prosperous and sometimes virtuous republic and then a dissolute and corrupt empire that was destined to be mined for contemporary lessons by historians beginning with Edward Gibbon, whose first volume of “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” was fittingly published in the British empire in 1776.

There are almost as many causes cited for Rome’s collapse as there are historians. But the general sense is that the empire became too fat, flabby and unwieldy. As Gibbon put it, “prosperity ripened the principle of decay.” Rome’s decline came to be viewed with an air of tragic inevitability fraught with resonance. As Byron wrote in “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”: “There is the moral of all human tales; / ’Tis but the same rehearsal of the past, / First Freedom, and then Glory — when that fails, / Wealth, vice, corruption — barbarism at last.”

The most salient comparison between modern America and classical Rome, as Murphy notes, is that both have been blessed, and afflicted, with a sense of exceptionalism. In America this begins with John Winthrop exhorting his Puritan flock, who were about to settle the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “that we shall be as a city upon a hill.” Since then various presidents have described the United States in words that echo Cicero’s description of the Romans and their shining city upon seven hills: “Spaniards had the advantage over them in point of numbers, Gauls in physical strength, Carthaginians in sharpness, Greeks in culture, native Latins and Italians in shrewd common sense; yet Rome had conquered them all and acquired her vast empire because in piety, religion and appreciation of the omnipotence of the gods she was without equal.”

In Rome, the virtues of a republic were originally sustained by selfless leaders and warriors like Cincinnatus, who took up a sword to save the city but, when the battles were won, put it aside to take up a plow again. In both the reality and the lore of America’s founding, George Washington played that role. But Rome eventually became dominated by fixers, flatterers and bureaucrats who clung to power. Murphy, the editor at large at Vanity Fair, offers up comparisons with the city of Washington today that are provocative, if at times a bit stretched. He pokes at putative panegyrists like Midge Decter on Donald Rumsfeld, and he compares the Roman undercover operatives, the curiosi, to the eavesdropping programs of the National Security Agency. He even likens the marvels of Rome’s sewer system to the effluence to be found on the Internet: “Washington now drains into the blogosphere, another engineering marvel.”

| Rome had Pliny the Younger asking for patronage from the emperor. America has Jack Abramoff. |

The military strategist Edward Luttwak, in his 1976 book “The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire,” examined how Rome’s legions protected its frontiers. His thesis was that during the late stages of their empire the Romans resigned themselves to the fact that barbarian invaders would penetrate the borders. So cities began to wall themselves in, and “the provision of security became an increasingly heavy charge on society.” At the same time, the idea of citizen-soldiers drawn from all ranks of Roman society — including the educated and upper classes — gave way to legions that were hired and dragooned from the poor and from immigrants.

Similarly, Murphy worries about the toll the post-9/11 security apparatus is taking on America at a time when members of the educated elite no longer feel it their duty to serve in the military. He reports that 450 of the 750 graduates in the Princeton class of 1956 served, whereas only eight of the 1,100 in the class of 2004 did. America has begun contracting out many security functions to private companies, much as Rome farmed out its security to barbarian mercenaries. The problems that result are exacerbated when America tries to impose its values and institutions in distant lands. Drawing on the great reporting of others, most notably Rajiv Chandrasekaran in “Imperial Life in the Emerald City,” Murphy shows the absurdities that occur in places like Baghdad when the proconsuls and legions and contractors we send have no clue about the people they are dealing with.

Even in its prime as a republic, Rome had a web of patronage among the connected elite. Later, Pliny the Younger was the master of the patronage letter, repeatedly asking the emperor for favors. But by the empire’s declining years, the concept of suffragium, which had originally meant “ballot,” then the exerting of influence, had evolved into a word for outright bribery. Here Murphy has a target that is almost too easy. He quotes some of the e-mail of the lobbyist Jack Abramoff exhorting contributions from his clients, which does not stand up favorably to Pliny the Younger’s letters. “You iz da man! Do you hear me?! You da man!! How much $$ coming tomorrow? Did we get some more $$ in?”

Occasionally Murphy seems to overstretch his analogies or to treat America as if it were a society as distant and curious as ancient Rome. His erudite book occasionally feels like something written from the aloof perch of the Boston Athenaeum library, which it indeed was, rather than from firsthand observations of a Rotary Club meeting in the Midwest or an American Army base in the Middle East. Nevertheless, Murphy’s arguments, even when they fail to be fully convincing, are thought-provoking.

Laudably, he ends on some optimistic notes, and some prescriptions, rather than wallowing in declinism. “An empire remains powerful so long as its subjects rejoice in it,” the Roman historian Livy wrote. To that end, Murphy suggests, America needs to instill in its citizenry a greater appreciation for the rest of the world. At home, it should resurrect the ideals of citizen engagement and promote a sense of community and mutual obligation, rather than treating most government as a necessary evil. With its capacity to innovate and reinvent itself, and with its faith in progress, America need never become as stagnant as Rome. “The genius of America,” Murphy concludes, “may be that it has built ‘the fall of Rome’ into its very makeup: it is very consciously a constant work in progress, designed to accommodate and build on revolutionary change.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book Review, of Sunday, May 13, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |