| Want to send this page or a link to a

friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Tennis Nonwhites |

| _______________________________________________ |

|

|

| A history of black players, and an

autobiography by one who's still competing at the game's highest levels. |

|

|

| CHANGING THE NET |

| A History of Blacks in Tennis |

| From Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe |

| to the Williams Sisters. |

| By Cecil Harris and Larryette Kyle-De-Bose. |

| Illustrated. 267 pp. Ivan R. Dee. $26.95 |

|

|

| By TOURÉ |

FROM the start of their

professional tennis careers, Venus and Serena Williams seemed totally certain they were

champions; they marched through the tennis world with the ferocity of the young Mike

Tyson. James Blake was No. 9 in the world at the conclusion of Wimbledon this month; late

last year he was No. 4. But only twice in his career has he reached a Grand Slam

quarterfinal, and many have long sensed that his potential has been limited because he

doesn’t truly believe he belongs in big-time tennis. He’s cursed with the

unsureness of Dave Chappelle. Blake confirms this in his memoir, “Breaking Back”

(written with Andrew Friedman), when, early in his career, he drops a winnable match to

the great Patrick Rafter. “After the match, as we shook hands at the net, he leaned

in close, the zinc oxide he smeared under his eyes like war paint runny with sweat:

‘You could have beaten me today,’ he said, surprising me, ‘but I had the

sense that maybe you didn’t believe it yourself.’ He paused, then said,

‘Now do you believe?’ ... He perceived something about me that I wasn’t

even admitting to myself: I didn’t really believe that I belonged out there with the

best players in the world. I didn’t feel like I deserved to win.”

|

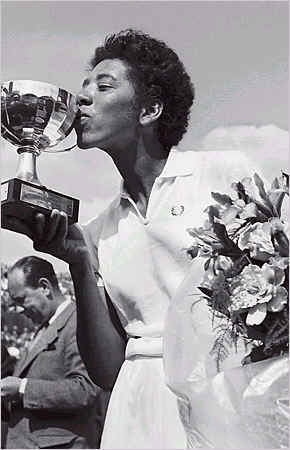

Bettman/Corbis |

| Althea Gibson won the French Open in 1956, above, and 10 other major

titles in the 1950s, but ended broke, reclusive and bitter. |

Back” is about more than tennis and race. That’s because Blake, like Ashe, is

smarter and deeper than most athletes, and also because in 2004 Blake lived his own year

of magical thinking. First, in a freak accident on a wet clay court in Rome, as he ran for

a drop shot he tripped and flew headfirst toward the net post. He turned his head at the

last second and dodged paralysis by inches, crashing into the steel pole with his neck.

“I wanted to do a quick analysis of the situation, but my mind was whirring much too

quickly. I was strangely disconnected from the world around me, in a place beyond pain and

discomfort. I hadn’t quite blacked out, but my eyes were closed and the darkness was

comforting, transporting. Deep down, almost subconsciously, I was aware that I had just

suffered a serious injury, and that once I opened my eyes, there was a terrible reality to

be confronted. So I lingered in the darkness, putting off the inevitable for just a few

seconds.” His neck broken, Blake returned to his hometown in Connecticut to spend

time with his father, who was dying of stomach cancer. After his death, Blake developed

zoster (shingles), which paralyzed the left side of his face. He ended up going back to

tennis’s minor leagues, the Challenger Series, to get his career going again. Soon he

was back in the majors, with more confidence and maturity. Valiantly he took Andre Agassi

to a fifth-set tie breaker in the quarters of the United States Open in 2005. Blake lost

that winnable match, but he was able to force a fifth-set breaker, he says, because of

what he had gleaned from his travails. He didn’t get down on himself when bad things

happened on the court, because he remembered his father’s strength and also because

he embraced something Pete Sampras had told him: “You have to have a short

memory.” You have to have the in-game amnesia that all athletes need to thrive. Now

that Blake is developing it, maybe he’ll finally win a Slam.

The problem with memoirs by active athletes is that guys still in the locker room feel

bound to keep that world a secret, and Blake is no different. I longed for a few stories

from behind the scenes about Andy Roddick, Rafael Nadal, even that rascal Vince Spadea,

but no. Blake says: “The ATP Tour is like a kind of traveling neverland, where no one

forces you to grow up. So a lot of the guys are indistinguishable from overgrown

adolescents.” But he never elaborates. Early in his career, during a tough match at

the United States Open, his opponent, Lleyton Hewitt, suggested that a black linesman was

making calls in favor of Blake because of their shared race. I was hoping for a fuller

story from Blake, but no.

| The unspoken but persistent

view that the're not welcome is 'a vibe that black tennis players have sensed for

decades.' |

Curiously, Blake gives the slightly fuller telling of that story to Cecil Harris and

Larryette Kyle-DeBose for their history of black tennis, “Charging the Net.”

Blake tells them: “We talked about it in the locker room, and he did apologize. ...

He said he didn’t mean for it to come out the way it did. ... I knew we would both be

on the tour for a long time, and I told him that if he said anything like that again, I

wouldn’t be so kind.”

“Charging the Net” is a wide-ranging history, built on more than 65

interviews, that tells in-depth stories about the lives of black tennis stars like Venus

and Serena; Arthur Ashe; Althea Gibson, the Wimbledon champ from Harlem who ended up

broke, reclusive and bitter; and Zina Garrison, the Wimbledon finalist who, during her

career, was dragged down by bulimia and a husband who, she says, encouraged her to stay on

the tour so he could continue his affair with one of her friends. The authors cover the

tennis diaspora, discussing famous umpires like Cecil Hollins, who feels he was kept from

advancement by racism; legendary coaches like Dr. Robert Johnson, who molded Ashe; and the

French stars Yannick Noah and Gael Monfils. There are some strange choices — they

barely mention two Africans now on the tour, Hicham Arazi and Younes el-Aynaoui, both from

Morocco, but give several pages to the Wimbledon winner Evonne Goolagong, an Australian

aborigine. Aborigines may be oppressed and darker-skinned, but does that make them black?

The original Australians are no blacker than, say, Vijay Amritraj of India, who played in

the ’70s and ’80s and acted opposite Roger Moore in “Octopussy.” Alas,

he’s not in the book. The authors claim that a black man named Edgar Brown “is

credited by some with introducing topspin” around 1900. The International Tennis Hall

of Fame and serious tennis historians recognize Herbert Lawford, Wimbledon champ in 1887,

as the introducer of topspin, but maybe they’re just racist.

|

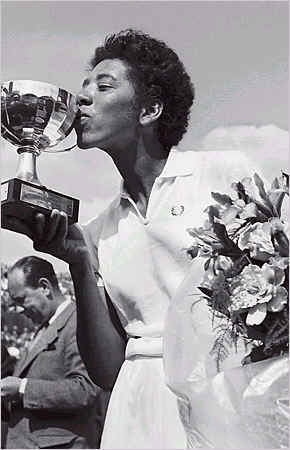

Tobis Melville/Reuters |

| Venus William |

Whereas Blake glosses over the subject of race, Harris, a sportswriter, and

Kyle-DeBose, an author and photojournalist, make racism a recurring theme, arguing that it

has dealt a devastating blow to black tennis dreams. They write, “The unspoken but

persistent vibe that you are not welcome, that others would be happier if you went away, a

vibe that black tennis players have sensed on the main tour for decades, makes it

difficult to find the rhythm and comfort zone needed to perform at your best.” Leslie

Allen, who played on the women’s tour in the ’80s, when players frequently

stayed with host families rather than in hotels, says housing was often hard to find:

“I’d go to a tournament where the family wanted to house the No. 1 seed. But

when that family found out that the No. 1 seed was me, then suddenly the housing

disappeared.” The great coach John Wilkerson, who taught Garrison, says black players

(in the authors’ words) “have not won more major championships because too many

of them believe deep down that they don’t belong in the sport.” Apparently, the

feeling that’s held Blake back has held back many. Touré is the author of

“Never Drank the Kool-Aid.” He was once ranked No. 1 in the men’s division

of the American Tennis Association. Next Article in Books (3 of 15) »Need to know more?

50% off home delivery of The Times. Ads by Googlewhat's this?

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book

Review, of Sunday, July 22, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of

democracy and human rights |