| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted May 30, 2006 |

Technology and Ease Of Credit Give an Edge To Identity Thieves |

|

Jeff Toping for The New York Times |

| Rose Seivert, a postal carrier, delivering mail recently to a high-security mailbox in a town house neighborhood in Phoenix. |

By JOHN LELAND |

and TOM ZELLER Jr. |

PHOENIX — In a Scottsdale police station last December, a 23-year-old methamphetamine user showed officers a new way to steal identities.

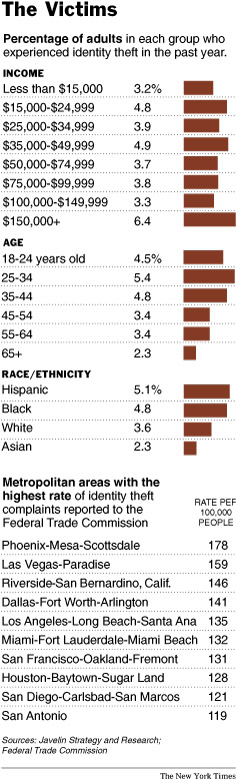

His arrest had been unremarkable. This metropolitan area, which includes Scottsdale and Phoenix, has the highest rate of identity theft complaints in the nation, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Even members of the Scottsdale police force have had their identities stolen.

But the suspect showed officers something they had not seen before. Browsing a government Web site, he pulled up a local divorce document listing the parties' names, addresses and bank account numbers, along with scans of their signatures. With a common software program and some check stationery, the document provided all he needed to print checks in his victims' names — and it was all made available, with some fanfare, by the county recorder's office. The site had thousands of them.

The data were not as rich as some found in stolen mail or trash bins. But for law enforcement officials here, this was another turn in a cat-and-mouse game in which criminals have outpaced most efforts to stop them.

"We're trying to keep up with the technology," said Lt. Craig Chrzanowski, who runs Scottsdale's property crimes division, including a computer crimes unit started two years ago. "But they're getting a lot better."

In an economy that runs increasingly on the instantaneous flow of information and credit — aggressively promoted by banks and credit card companies despite the risks — Phoenix and its surrounding area provide a window on one of the system's unintended consequences.

According to a Federal Trade Commission survey in 2003, about 10 million Americans — 1 in 30 — had their identities stolen in the previous year, with losses to the economy of $48 billion. Subsequent surveys, by Javelin Strategy and Research, a private research company, found that the number of victims had declined to nine million last year but that the losses had risen to $56.6 billion.

In Arizona, one in six adults had their identities stolen in the last five years, about twice the national rate, according to the Javelin survey.

Arizona officials have responded with a preventive mantra: shred all documents and avoid giving Social Security numbers or bank account numbers to strangers over the telephone or the Internet. The State Legislature has passed tougher penalties for people caught stealing or trafficking in stolen identities.

But the real problem, many officials and consumer advocates say, lies elsewhere. In recent years banks have campaigned energetically to extend more credit to more people with fewer hassles, and retailers and consumers have embraced instant, near-anonymous access to credit.

Last year a group of prosecutors, law enforcement officers and security executives from banks and credit card associations met to discuss ways of curbing identity theft. The group had plenty of ideas, including PIN numbers or fingerprint verification for all credit card purchases and a ban on mailings that include blank checks.

But all ran counter to the promotional campaigns of banks and, banks say, to the desires of consumers.

"There's a disconnect between corporate leadership at financial institutions and their security departments," said Brad H. Astrowsky, a former prosecutor who was part of the group. "Marketing people are ruling the day in banking. They can do things to fix the problem, but they have no incentive and motivation to do it. Preventing something from happening is a cost. What's the benefit? It's hard to quantify."

| A Hot Spot for Thieves |

Several factors converge to make Arizona a hot spot for identity theft. Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, is one of the fastest-growing counties in the nation, according to the Census Bureau, and its growth exaggerates trends that exist in many communities: a mobile population and high numbers of immigrants and retirees. It also has a heavy traffic in methamphetamine.

Methamphetamine users, whose binges keep them up for days in a row, have the time to sort through trash or old mail for Social Security numbers, bank account numbers or other identifying information, said Andrew P. Thomas, the county attorney. Dealers trade drugs for stolen identities that they use to launder their profits. Nearly half the identity theft cases in Mr. Thomas's office have a connection to methamphetamine, he said.

At the same time, he added, "More than half of the illegal immigrants entering the U.S. come through Arizona," creating a market for fraudulent Social Security numbers and driver's licenses.

Though Arizona passed the nation's first identity theft law in 1996, law officers say they are fighting a crime that is as swift and adaptive as the economy it exploits.

The newest wave of thefts here involves copying the magnetic strip from a victim's credit card onto the back of another. When thieves use the doctored cards, the transactions are charged to their victims' accounts. "Even if the cashier asks for my driver's license, the name on the front is going to match," said Todd C. Lawson, an assistant attorney general in Phoenix who specializes in identity theft prosecutions.

|

The machine to copy the magnetic strip, Mr. Lawson added, is the one nearly every hotel in America uses to recode room key cards.

And the county's Web site, which earned a place in the Smithsonian's permanent research collection on information technology innovation, has made Social Security numbers and other information, once viewable only by visiting the county recorder's office, accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. Police officers and prosecutors in Phoenix knew of just two cases involving public records, but most victims do not know how their identities are stolen.

For local law enforcement, pursuing even low-tech, small-time thieves is often complicated and expensive. The victim could be in Arizona, the thief in another state and the transactions spread all over the world. "If someone goes on the Internet and buys goods from Bangladesh, do you call witnesses from Bangladesh?" asked Barnett Lotstein, a special assistant county attorney.

Mr. Lawson said, "I don't think we prosecute 5 percent of it."

On a recent afternoon, Lt. Russ Skinner, who runs the county sheriff's computer crimes division, hefted three vinyl binders onto a wooden table. For the detectives in his unit, this is what the "crime of the 21st century" looks like: photographs of litter-strewn hotel rooms, and of a 33-year-old woman in various stages of methamphetamine-fueled decline.

When detectives caught up with her last August, after nearly three months of investigation, the woman was paying other users to steal mail for her — especially preapproved credit offers — and had parlayed those into credit cards or fraudulent accounts in 46 different names. She had secured housing, utilities and a series of small online loans in her victims' names.

"She wasn't the smartest or the most creative," Lieutenant Skinner said. "She just knew how to get it done."

| A Connection to Drug Use |

In the past, a drug user who needed money might go into a convenience store with a gun, Lieutenant Skinner said. "They're on the surveillance camera. They might get shot. They might get stopped in the parking lot for having a broken taillight," he said. "Now they can just sit at a computer, no one sees them and they can buy whatever they want."

Officials here began to notice a sharp rise in identity theft about five years ago, said Paul K. Charlton, United States attorney for the District of Arizona.

"The first tip-off was that we started to see a lot of mailbox break-ins by tweakers," Mr. Charlton said, referring to methamphetamine users.

| How to Avoid Identity Theft | |

| Though no ono's identity is safe from theft, consumer groups advise these steps. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When police officers raided home methamphetamine laboratories that were then proliferating on the outskirts of town, they found stacks of stolen mail or notebooks filled with credit card information. They also found thieves were using acetone, an ingredient used in methamphetamine production, to "wash" the ink off checks, a simple means of identity fraud.

These small laboratories lend themselves to identity theft rings, said John C. Horton, a White House aide in the Office of National Drug Control Policy. In a laboratory, one or two people typically have some technical knowledge, and others specialize in procuring materials.

Identity theft rings follow the same pattern, with a handful of grunts stealing mail for one person who knows how to turn the information into credit cards or checks, Mr. Horton said. "It doesn't seem to happen with cocaine or heroin because we don't produce heroin and cocaine in this country," he said. "Meth production is to some degree a social activity in the same way as identity theft."

Though the Arizona police have closed many laboratories, the identity theft rings have survived or multiplied.

"You can jimmy one open and get everyone's mail at the same time," said Mr. Lawson, the prosecutor. After numerous break-ins, the Postal Service has spent $12 million on reinforced mailboxes, but many communities here still have the old ones.

Some thieves drive around neighborhoods with their laptops until they find a resident's unsecured wireless Internet connection. If the police investigate a fraudulent purchase, they will trace it to the customer with the connection, not to the thief who placed the order.

Since 1994, a Phoenix security officer named Bob Hartle, frustrated by his own experience with identity theft, has led an often lonely campaign for tighter controls on organizations that handle people's data, and curbs on the way credit card companies, banks and stores grant credit.

Data breaches in the last year have exposed the personal information of more than 80 million Americans, according to the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that follows identity theft. On May 3, a thief stole computer disks holding the names, Social Security numbers and other information of 26.6 million veterans from the residence of a Department of Veterans Affairs employee who had taken the data home without authorization. In most states, organizations are not required to tell consumers if their identities have been compromised.

"It's the sharing of data without necessary safeguards that enables this crime to grow as it has," said Torin Monahan, an assistant professor of justice and social inquiry at Arizona State University. "The response is always 'protect yourself, go to these workshops, get a shredder.' That diverts attention away from the extent to which these are systemic problems."

Seventeen states have passed "credit freeze" laws enabling consumers to prevent banks or credit agencies from issuing new accounts in their names.

But here, as in other states, businesses have successfully opposed such legislation.

"They're fighting us tooth and nail," said Mr. Hartle, who runs ID Theft Services Inc., a nonprofit organization that provides free help for victims.

"Banks, credit card companies, retailers want to make it easy to buy," Mr. Hartle said. "They write off identity theft as a cost of doing business. So whenever legislation comes up that's going to cost them money, they throw themselves against it."

Nessa E. Feddis, senior federal counsel for the American Bankers Association, said freezing credit could create problems for consumers, especially if they needed to get a new cellphone or change residences in a hurry.

"A credit freeze is one of those things that sounds like a good idea, but people don't realize how often they need to use their credit report," Ms. Feddis said. "There's a balance between security and convenience."

She continued, "We all want fraud to go away, but we don't want to take 20 extra minutes every time we do online banking. We like buying airline tickets online, but there's a risk."

Though consumers worry about identity theft, Ms. Feddis said, banks absorb most of the losses.

Credit card companies point to new monitoring systems that have reduced loss from fraud as a percentage of overall transaction volume. At Visa, fraud accounted for 7 cents per $100 in transactions, down from 18 cents per $100 in 1990. "We could have a system reducing fraud to zero basis points, but it wouldn't meet what consumers are demanding," said Rosetta Jones, a Visa spokeswoman. "We need to deliver what consumers want in a way that is secure."

Fritz M. Elmendorf, a spokesman for the Consumer Bankers Association, described a chess match with identity criminals. For example, banks now protect prescreened credit card offers with address-matching technologies that make it harder for thieves to have cards sent to a drop address, Mr. Elmendorf said.

"There are more tools today than ever to ascertain the identity of a credit applicant," he said. "And the industry can point to a lot of things — some of which they won't talk about in detail — to validate people."

In the community of Chandler, southeast of Phoenix, Bobby Joe Harris questioned the efforts of businesses and banks to protect his identity.

Mr. Harris, 60, is a retired police chief. His wife, Judy, is a retired bank manager. Last December, Mrs. Harris was shopping at a Sam's Club store when a cashier said their membership had been canceled. When Mr. Harris tried to reactivate their membership in January, he learned that the store had issued a new credit card on their account to a woman who had said she was the couple's daughter.

"I don't have a daughter," Mr. Harris said. "I told the lady, 'I don't think so.' "

In two phone calls, possibly working with a store employee, the thief had raised the Harrises' credit limit to $10,000 from $3,500 and then to $15,000, and had run up charges of $11,093. No one had called them.

"It was only by luck that we found out," Mr. Harris said.

| Seeking Protection |

Though like most consumer victims the Harrises did not have to pay the bogus charges, they now pay $220 a year to LifeLock, a protective service that started last September in Phoenix.

The company's core service is simple: Whenever a bank or other business requests to look at a LifeLock subscriber's credit history, the company gets a fraud alert asking to confirm that the customer applied for credit. Federal law empowers consumers to get these alerts on their own, but they must reapply regularly to one of the three companies that issue credit reports.

Other companies offer different protections. None has had to prove that its services are effective.

When the Maricopa County recorder's office began posting records online in 1997, it was one of the first in the country to do so. Since then, legislatures in other states, including New York and Florida, have wrestled with whether — or how — to make their information available online.

A law in Florida requires that all Social Security and financial account numbers be stripped from online records by 2007, although new legislation may delay that another year.

In Phoenix, the county recorder's office posts 8,000 to 10,000 documents a day. Most are innocuous, but some, including divorce decrees and tax lien records, have sensitive information.

"I'm not insensitive to people's fear," said Helen Purcell, the county recorder. "I have the same fear. My information is out there, too." But it is far too late to start editing Social Security numbers or other data from the county Web site, she said. "We have 100 million documents out there now."

In the absence of full security, Arizonans cling to what protections they can. On a recent morning in Ventana Lakes, a development of older residents northwest of Phoenix, Lois Owen and Joan Schanks joined a small procession of neighbors to a community "shredathon" organized by the attorney general's office and AARP. Since the first shredathon last fall, residents around the state have carted 12 tons of paper to the mobile machines, in many cases supplementing the shredding they do at home.

"It's a big relief," Ms. Schanks said as she watched 20 pounds of old bank statements disappear. Yet even with the shredding, the residents here cannot begin to estimate how many people have their personal information, or how tempted any of those individuals may be to sell that information, Mr. Lawson, the prosecutor, said.

"You can take all the precautions you want," he said. "But everyone's exposed to a certain extent."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Tuesday, May 30, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |