| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted November 11, 2008 |

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

| AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE GETTY IMAGES | ||

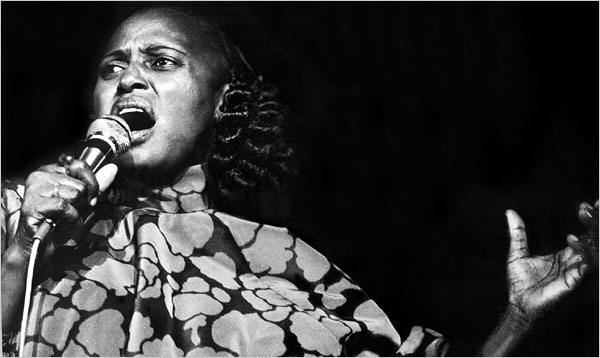

| Miriam Makeba during one of her concerts in 1978. |

| By JON PARELES |

|

|

|

|

|

| SALVATORE LAPORTA/ASSOCIATED PRESS | |

| Miriam Makeba performing barefoot at a concert in Castel Volturno, in Southern Italy, on Sunday night, just before she died. |

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |