| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted June 9, 2003 |

|

Striking It Poor: Oil as a Curse |

| By DAPHINE EVIATAR |

THE pipes are already laid in southern Chad, where they snake south underground through tropical forests from the oil fields of Doba to a marine terminal off the coast of neighboring Cameroon. At the port of Kribi, the 660-mile pipeline will empty up to 250,000 barrels a day of coveted crude into tankers waiting to transport the unctuous black gold to Western markets.

The largest energy infrastructure development in Africa, the Chad-Cameroon pipeline is to begin operation later this year. Built by a consortium of oil companies led by Exxon Mobil, it is expected to provide average annual revenue of $50 million. The World Bank Group has invested more than $180 million in the project, insisting that the pipeline's profits could significantly improve the lives of Chad's residents, most now living in squalor, by paying for services like health care, education, paved roads, electricity and sewer systems.

Many critics find that assessment surprising, given that scholarly studies for more than a decade have consistently warned of what is known as the resource curse: that developing countries whose economies depend on exporting oil, gas or extracted minerals are likely to be poor, authoritarian, corrupt and rocked by civil war. And now a draft of a report commissioned by the bank itself has essentially concluded that the bank's previous efforts to promote such projects in poor countries has done more harm than good.

______________________________ |

| In the third world, development may be the opposite of enrichment |

______________________________ |

Both former bank officials and outside academics have complained that bank policy often contradicts the expert research. "There's a big disconnect between World Bank operations and World Bank research, said William Easterly, an economics professor at New York University who spent more than a decade as a senior adviser at the bank. "There's almost an organizational feud between the research wing and the rest of the bank. The rest of the bank thinks research people are just talking about irrelevant things and don't know the reality of what's going on on the ground."

|

|

In this latest case, using the bank's own internal documents, the report's author, Melissa A. Thomas, found that the bank had for years focused on promoting foreign investment in these industries without considering how the countries' governments were managed and what they were likely to do with the money. As a result, she said, in most of the nations studied — Chile, Ecuador, Ghana, Kazakhstan, Papua New Guinea and Tanzania — the bank's work had not achieved its development goals.

Even when the bank made loans conditional on a country's promise to make public how it had spent its revenues, the projects did not produce economic benefits. Ms. Thomas, a political economist at the University of Maryland, concluded that the bank should stop financing these so-called extractive industries in countries "whose governments lack the capacity to benefit from or manage such investment."

Rashad Kaldany, director of the oil, gas, mining and chemicals department of the World Bank Group, said it was "awkward for me to comment," because the report was still a draft, but added: "We certainly feel that the issues of good governance and corruption are of paramount importance for development. This is what we're focusing on more and more in all our activities."

But scholars are skeptical. "You get the sense that the left hand doesn't know what the right hand is doing at the World Bank," said Scott Pegg, a political science professor at Indiana University. He relied on World Bank research for a recent report — commissioned by Oxfam America, Friends of the Earth, Environmental Defense, Catholic Relief Services and the Bank Information Center — that sharply criticizes the impact of extractive industries in Africa.

Academics hired by the bank have criticized its work before. Some of the most important research on the resource curse has been done by bank economists. In a pioneering 1988 book issued as a World Bank Research publication, "Oil Windfalls: Blessing or Curse?," Alan H. Gelb, chief economist for the bank's African regional office, found that contrary to assumptions popular at the time, oil wealth had made conditions in most countries worse. And Paul Collier, an Oxford University economics professor who now heads the bank's development research group, has demonstrated repeatedly that oil, gas and mining wealth has fueled brutal civil wars. Advocacy groups have used these findings to urge the bank to stop supporting oil and gas projects.

Bank officials say they have taken steps to respond to the failings pointed out by critics. Last year the bank began a formal review of its support for these industries.

"We said from the outset that if there's a broad consensus that these projects don't contribute to development, and if the World Bank Group's role is not clear or questionable, we would pull out," Mr. Kaldany said. But he added, "I feel confident we will be able to convince all stakeholders that there is a positive role for the bank to play."

At a conference on this issue held last month in Washington, Clive Armstrong, principal economist for the bank's oil, gas, mining and chemicals division, said the bank, for the first time, had made its loans to Chad on the condition that the country's notoriously corrupt government use the money earned by the pipeline for its people. "In Chad, we've gone as far as we can to ensure that revenues are used well," Mr. Armstrong said in a telephone interview.

To receive bank loans, Chad had to adopt anticorruption laws and promise to spend most of its oil money on projects like health care and rural development. It pledged to publish reports on how the funds were spent and to create an independent oversight committee to ensure that it followed the rules.

But critics in the academic world and at nonprofit groups point to large loopholes in the plan. Chad can unilaterally change the rules about allocation of oil revenues after five years, even though profits are not expected to start flowing until four years from now. The revenue law applies to the country's three existing oil fields, but not to future ones, and the criteria used to allocate the profits among the companies, the government and the different regions of the country are unclear.

Already, a bank inspection has disclosed a long list of areas in which the project has been violating bank rules and has warned that while pipeline construction is years ahead of schedule, the government lags far behind in carrying out the promised social and environmental programs. As Ms. Thomas wrote in her report about the Chad project, "It seems likely that the bank has underestimated the governance risks."

What is more, in a violation of its promise to spend the oil money on social services, Chad's president, Idriss Déby, spent the first $4.5 million he received in 2000 as a "signing bonus" from the oil companies to buy weapons to use against rebels.

Mr. Kaldany called Mr. Déby's action "one big hiccup early on," but added: "After this was disclosed, we took a very active role. The president agreed to repay these funds and to use them as originally intended."

Bank officials add that without their involvement, the pipeline's impact would surely be worse. For the countries concerned, these industries are "seen as a major source of development," Mr. Armstrong said. "You can't realistically say, `Don't develop them.' The issue is: how can you make sure they're developed in a way that leads to positive benefits? That's what we're trying to do."

But some scholars disagree. Terry Lynn Karl, a political science professor at Stanford University and author of "The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States" (University of California, 1997), argues that Chad would be better off without the pipeline.

"Revenues flowing through incapable or corrupt structures will give you perverse outcomes," she said at the Washington conference. Not only is the money going to be put to bad use, she predicted, but encouraging dependence on natural resources also tends to result in corruption and a single-industry economy: "When the crisis comes, it's much worse than it would have been otherwise."

|

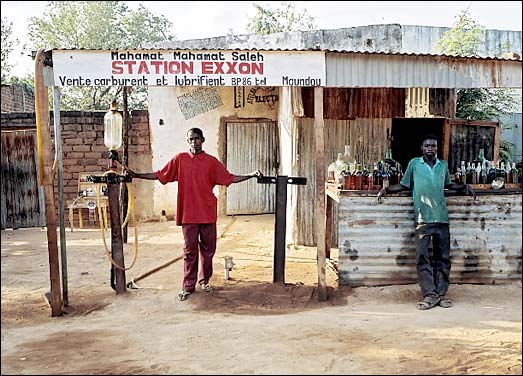

Corbis |

| Bottles of gas and oil at a station in Doba, Chad. Suppliers are smuggled in because Chad does not have its own production system. The new pipeline, tapping the country's oil reserves, is supposed to change that. |

Mr. Easterly, who used to work at the bank, said that given their poor record, the bank should not finance these industries. "The bank can try to influence management of those natural resource revenues, but it doesn't have that much leverage," he said. "And its record on enforcing codes of conduct on the part of borrowing governments is dismal."

To some extent, the World Bank's limited ability to change governments is built into the institution. The bank was created in 1944, along with the International Monetary Fund, to help finance the postwar reconstruction of Europe. The bank was conceived as a nonpolitical instrument that would lend money to governments and finance private investments based on technical economic considerations, Bruce Rich, a lawyer with Environmental Defense, explains in his book, "Mortgaging the Earth: The World Bank, Environmental Impoverishment and the Crisis of Development" (Beacon Press, 1994). Although over time the bank's focus has shifted to development, its original charter states that "political or other noneconomic influences" are strictly off limits.

For decades, a government's human rights abuses or rampant corruption were not supposed to affect lending decisions. As the bank's president, James D. Wolfensohn, has famously noted, corruption was long the forbidden "C-word" inside the bank. Although that climate had begun to change by the mid-1990's, it is still difficult for the institution — whose board consists of countries that finance and borrow from it — to criticize its members openly.

So, to some critics, the safeguards for the Chad project signal a step in the right direction. "There are some innovations in that program that I'd like to see used in other countries," said Michael Ross, professor of political science at the University of California at Los Angeles, who has written several articles showing the connection between a dependence on natural resources and poverty.

Mr. Armstrong acknowledges, however, that the bank is not likely to replicate such stringent conditions elsewhere. A bank report released in May recommends a purely voluntary strategy to reduce corruption and improve management of resource-dependent countries. A government's participation in the plan would not be a condition for receiving bank loans.

Critics are skeptical that such limited measures will work, and they complain that the bank is not really open to questioning its continuing support for oil, gas and mining projects.

As evidence, they point to a conference held in Bali, Indonesia, in April as part of the bank-sponsored "extractive industries review." There, members of 15 environmental and other advocacy organizations walked out in protest, claiming the process was a sham: the group of reviewers set up by the bank had already circulated its draft conclusions supporting the bank's oil, gas and mining investments, even though more conferences organized to gather information from concerned groups and individuals in Asia, the Middle East and Africa had not yet taken place.

Copyright The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Books, of Saturday, June 7, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |