| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted October 21, 2007 |

|

||

|

||

AKHTAR SOOMRO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

||

| A Pakistani worker placing a banner for a religious program on a pole in a commercial area of Lahore. |

By JOHN KIFNER, |

DAVID ROHDE, |

BILL MARSH and |

RENEE RIGDON |

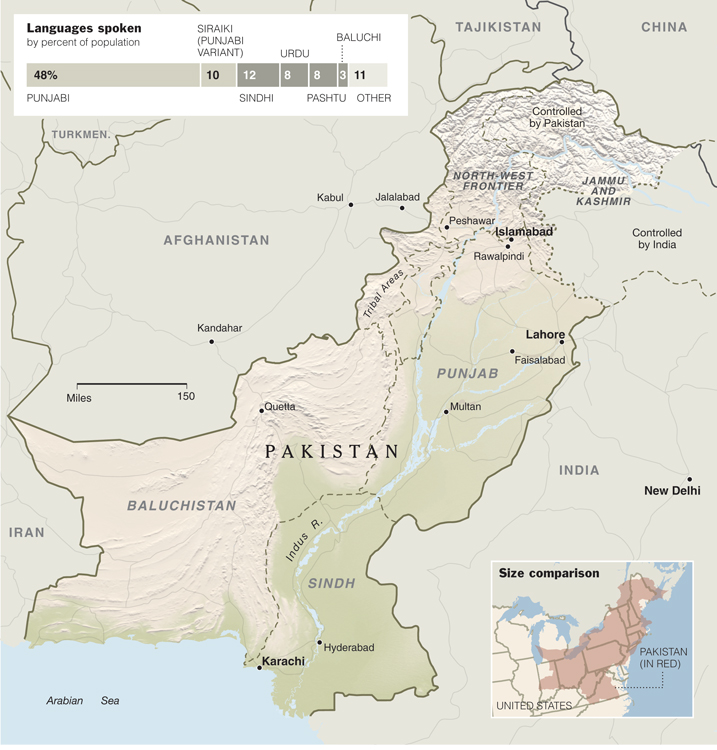

ALTHOUGH created as a homeland for Muslims when it was separated from mostly Hindu India at the breakup of the British Raj in 1947, Pakistan from the beginning has been plagued by chaos and violence. It is not so much a nation-state as an unwieldy collection of competing ethnic groups, tribes, castes and interests.

Indeed, the return of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto last week to join an uneasy coalition with the selfappointed president, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, was a product of a struggle between civilian and military authority that has defined the country’s politics. Her father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, was ousted in a military coup in 1977 and hung by Gen. Muhammad Zia ul-Haq two years later.

Last week, Ms. Bhutto herself suggested that the bomb blasts that ripped through a delirious crowd in Karachi and nearly succeeded in killing her had their roots in the long, intertwined relationship of fundamentalist Islamic groups with the army’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence agency.

The agency funneled money to Afghan mujahedeen when they fought the Soviets. It has supported Islamic separatists in Kashmir. And it helped create the Taliban. And while the United States regards General Musharraf as a crucial ally in the war on terrorism, recent intelligence estimates say that Al Qaeda has been able to regroup in the tribal areas along the Afghan border. Concerns about the terrorist camps and the country’s stability are heightened by the fact that Pakistan has nuclear weapons.

Those conflicts have played out against Pakistan’s other regional, ethnic and class divisions. Each of the four main ethnic groups — Punjabi, Sindi, Baluch and Pashtun — has its own interests. Pakistan’s Muslims are overwhelmingly Sunnis. But there are also Shiites, who are frequently attacked by Sunni fundamentalists who consider them heretics.

|

AKHTAR SOOMRO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| A family on a motor bike in Lahore. |

Although there is a growing middle class in the cities — these Pakistanis formed the backbone of demonstrations against General Musharraf for firing the chief judge of the Supreme Court last spring — a great many of Pakistan’s 165 million people are desperately poor. (Its total population is bigger than Russia’s.) With the central government weak and often corrupt, much of the real power has been held by the army and a class of hugely wealthy feudal landholders, who include Ms. Bhutto herself.

| PUNJAB: THE CENTER OF POWER |

Home to about half of Pakistanis, as well as Lahore, the country’s thriving second city and its cultural heart. Punjabis dominate the federal machinery and the army, much to the unhappiness of Pakistan’s other ethnic groups, all minorities.

Lahore sits not far from the Indian border (the only land bridge across the border is a 30-minute drive away) and is poised to benefit from the gradual opening of trade between the two rivals. Like all of Pakistan’s major cities, it is booming, with an independent news media and an elite and highly educated upper class.

A growing urban middle class has prospered under General Musharraf. Rural Punjab, by contrast, is largely poor and agricultural. Southern Punjab produces most of the country’s economically critical cotton crop.

There, especially, feudal arrangements persist. Even in this most fertile part of the country, arable land and water for irrigation are inadequate.

| WHAT THEY SEEK |

Punjabis are accustomed to being the public face of Pakistan. They feel the rivalry with India especially strongly. The urban elites are impatient for democracy and unhappy with the United States after its invasion of Iraq. General Musharraf, once popular in Punjab, is no more, adding to anti- American feeling. Water is a source of great tension between provinces — the agricultural sector has its eye on water from the frontier provinces. Much of the country’s water now comes from the disputed territory of Kashmir, adding to conflict with India.

| SINDH: IN PUNJAB'S SHADOW |

Largely rural and agricultural, Sindh is Ms. Bhutto’s power base. The farm areas are dominated by wealthy feudal families — like the Bhuttos — who employ impoverished local Sindhis to work the land.

But Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and main port, is a polyglot megalopolis dominated by a different group known as mohajirs — Muslims, many of them civil servants, who fled from India during the fighting over the 1947 partition. (Islamabad, the capital, was built from scratch to house the government.)

There have long been violent clashes between the Mohajir National Movement (MQM in the Urdu language) and rival parties, including Ms. Bhutto’s. The MQM is allied with General Musharraf and has a reputation for thuggish politics. It was the main instigator of deadly rioting in May after General Musharraf’s dismissal of the Supreme Court Chief Justice Iftikar Mohammed Chaudhry.

|

MOHAMMAD ALI/REUTERS |

| Harvesting in Sindh province. |

As in many corners of Pakistan, a local liberation movement percolates, this one Sindhi.

| WHAT THEY SEEK |

|

THE NEW YORK TIMES |

Sindhis chafe at the Punjabi-dominated central government and army, believing that their province is shortchanged in respect and government largess. The province is largely dry, water is inadequate and energy and education needs are not fully met — as in the rest of the country.

| BORDERLAND: THE WILD, WILD WEST |

Rugged, mountainous, this is the land of the Pashtun, where the government’s writ does not run.

Fierce mountain tribesmen, the Pashtun straddle the Durand Line, the border the British drew in 1893 between Pakistan and Afghanistan. In practice, the line is nonexistent — impossible to seal and riddled with smugglers’ trails.

The Pashtun live by a strict code called Pushtunwali which requires them to protect their guests (like Osama bin Laden) and fight foreign invaders.

The North-West Frontier Province and two of the seven Federally Administered Tribal Areas known as North Waziristan and South Waziristan have become havens for a regrouping Al Qaeda and other foreign fighters, including Uzbeks. There has been heavy fighting recently, but much of the territory is lost to the government. Tribesmen captured some 250 Pakistani soldiers and are still holding them.

|

RIZWAN SAEED/REUTERS |

| Policemen examine a damaged gas pipeline in Quetta that was blown up by suspected militants in February. |

| WHAT THEY SEEK |

To be left alone.

| BALUCHISTAN RESTIVE |

A large, sparsely settled and natural-gasrich region with a clan-based population of ethnic Baluchis and Pashtuns. It is badly lacking in water and good roads.

Baluchistan borders Afghanistan and Iran and has extensive smuggling, mostly of heroin, with both countries. Its main city, Quetta, has become a refuge for Taliban fighters and the site of a command council, or shura, that directs attacks in southern Afghanistan.

| WHAT THEY SEEK |

Baluchi grievances are largely economic: they want higher royalties for their natural gas and a larger share of government resources. “They have a welldeveloped sense of grievance and a culture that reinforces it,” said Teresita C. Schaffer of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. The province, she said, is more or less in a perpetual state of rebellion.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Week in Review, Sunday, October 21, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |