| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted September 14, 2003 |

| Soft Voice Urges Europe to Carry a Bigger Stick |

|

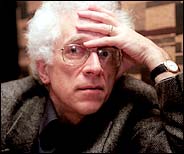

Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times |

| Tzvetan Todorov, a Bulgarian historian and philosopher, has entered the debate over trans-Atlantic relations. |

By ALAN RIDING |

PARIS, Sept. 12 — Tzvetan Todorov is something of an outsider in French intellectual circles. Born in Bulgaria on the eve of World War II, he was raised and educated under a Stalinist regime before moving to France in 1963. He is married to the Canadian novelist Nancy Huston, and he frequently lectures at American universities. His life has required him to see the world from different angles. As a social critic, historian and moral philosopher, he is a man of nuances.

In joining the debate about the state of trans-Atlantic relations, Mr. Todorov has therefore done so not as a French academic — he is director of research at the prestigious National Center of Scientific Research here — but as a European who is as alarmed by the unilateralist approach of the Bush administration as by the reluctance of Europe to take the necessary measures to defend its own interests.

Indeed, the most radical recommendation of his new book, "The New World Disorder: Reflections of a European," is that Europe should abandon its "pacifism and passivity" and rearm. He celebrates the fact that war is no longer possible within Europe. "But the whole world has not been pacified," he said in an interview in his Left Bank home. "Our potential enemies are no longer inside Europe. We must join forces to defend ourselves against these external enemies."

In that sense, Mr. Todorov shares the diagnosis of Europe's basic dilemma — that its "soft" power of diplomacy, foreign aid and multilateralism can be effective only if twinned with "hard" military power — that was offered by Robert Kagan in a much-debated article last year in the Hoover Institution's Policy Review, later expanded and published as a book, "Of Paradise and Power: America and Europe in the New World Order" (Knopf).

"The New World Disorder" is one of several new French books to address the current global crisis. In "West Versus West," the French philosopher André Glucksmann offers a strong defense of Washington's invasion of Iraq. And in another, "In the Name of the Other: Reflections on the Coming Anti-Semitism," Alain Finkielkraut warns that anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism are becoming synonymous in some parts of the world.

What perhaps distinguishes Mr. Todorov's book, though, is its lack of stridency. Even in print, his voice is soft. A prolific author, he has covered a vast spectrum of theoretical and historical subjects in his books, ranging from literary criticism to essays about Soviet-era concentration camps in Bulgaria and about how Bulgaria's Jews were in the main saved from Nazi slaughter. In this book, his first to address today's world, he again tries to apply reason over emotion.

"You cannot place immediate contentment before everything else," Mr. Todorov said, echoing Mr. Kagan's view that Europe's concern for preserving its "paradise" — its comfortable way of life — had made it insular and ineffective as a global political force. "You must be able to defend your values."

But the logic of adding a unified army to the European Union's continuing economic and political integration is accepted more in theory than in practice. Not only has the United States viewed sporadic European efforts to create an independent defense capability as threats to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, but Europe's leading powers — notably Britain, France and Germany — have shown little readiness to surrender sovereignty in this area.

"It's a bit like the French countryside," Mr. Todorov said with a smile. "The mayor of one small village will never agree to fuse with a neighboring village to be more efficient and have more resources, because one of the two mayors will lose the status of Monsieur le Maire. At the level of governments, it's equally ridiculous."

In analyzing American national interests in the post-cold war era, Mr. Todorov takes the long view. "We have gone from the world of George Orwell, where large empires confronted each other, to the universe of Ian Fleming and James Bond, where a megalomaniac billionaire hidden in a cave sends planes against American cities," he said, referring to the terrorist attacks of Sept 11, 2001.

But while this represents a major change, he believes that Washington's response has not served the best interests of the United States. He has the advantage that his book was completed after the American and British occupation of Iraq and, like many on both sides of the Atlantic, he now worries that "terrorism has been strengthened since the Iraq invasion, instead of being reduced."

But his principal reason for opposing the intervention in Iraq was that it lacked the legitimacy of, say, the 1991 Iraq war or the ouster of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. And it is this, more than anything, he believes, that has fed anti-Americanism: "It seems to me that Washington does not care enough today to give legitimacy to its acts in the eyes of the world."

While the United States has traditionally oscillated between isolationism and a desire to manage the affairs of the world, he said, what is new is the combination of self-righteousness and extraordinary military power.

But this approach, designed by what he calls the dominant "neo-fundamentalist" group in Washington, is doomed, he believes: "This mission of extirpating evil, of imposing good by force, is a policy that more closely resembles that of communism or the permanent revolution than a liberal agenda. For me, `liberal imperialism' is a contradiction. One cannot impose the liberal spirit by force, one cannot impose freedom at the point of a bayonet."

| A thinker against both pre-emptive and passive. |

More relevantly, he argues, the United States lacks the will to intervene everywhere that freedom is threatened. "It intervenes only in certain cases that coincide with its clearly defined interests," he said. "This means that in the eyes of the world it intervenes to defend its interests, not to defend justice. But an empire cannot maintain itself only through force of arms. It also needs to impose itself through legitimacy."

Mr. Todorov accepts that there are occasions when the use of force is necessary, but he notes that the West did not intervene to halt the two greatest genocides since World War II, in Cambodia and Rwanda. More often, he added, other forms of pressure on a repressive regime are more effective and less dangerous, not least the containment policy used by the West against the Soviet Union. But for this, he believes, it is better for the United States to work hand in hand with a Europe that can also defend Western values and interests.

Before this can happen, though, Europe must become what he calls a "quiet power." And he sees this occurring as Europe moves closer to political integration, starting perhaps with a small "hard core" group of nations unifying their armies. "It need not rival the United States," he said. "The United States should be its privileged ally. But it also need not be submissive to the United States."

Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of September 13, 2003.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |