| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

More Special Reports |

| Posted April 14, 2006 |

| Path to Deportation Can Start With a Traffic Stop |

|

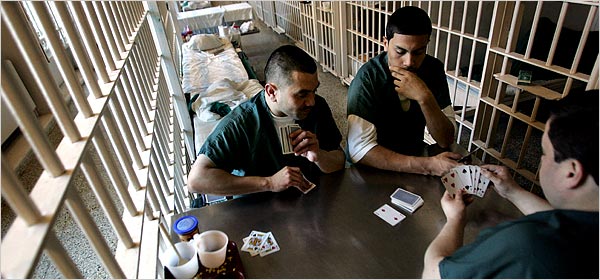

Ruth Fremson for The New York Times |

| Henry Rosales Lopez, left, and Fredy Reyes are among the illegal immigrants in custody in Suffolk County, N.Y. |

By PAUL VITELLO |

While lawmakers in Washington debate whether to forgive illegal immigrants their trespasses, a small but increasing number of local and state law enforcement officials are taking it upon themselves to pursue deportation cases against people who are here illegally.

In more than a dozen jurisdictions, officials have invoked a little-used 1996 federal law to seek special federal training in immigration enforcement for their officers.

In other places, the local authorities are flagging some illegal immigrants who are caught up in the criminal justice system, sometimes for minor offenses, and are alerting immigration officials to their illegal status so that they can be deported.

In Costa Mesa, Calif., for example, in Orange County, the City Council last year shut down a day laborer job center that had operated for 17 years, and this year authorized its Police Department to begin training officers to pursue illegal immigrants — a job previously left to federal agents.

In Suffolk County, on Long Island, where a similar police training proposal was met with angry protests in 2004, county officials have quietly put a system in place that uses sheriff's deputies to flag illegal immigrants in the county jail population.

|

Ruth Fremson for The New York Times |

| The Rev. Cardona, center, leading a Mass in Spanish for inmates, many of them illegal immigrants, at the Suffolk County jail. |

In Putnam County, N.Y., about 50 miles north of Manhattan, eight illegal immigrants who were playing soccer in a school ball field were arrested on Jan. 9 for trespassing and held for the immigration authorities.

As an example of the uneven results that sometimes occur in such cross-hatches of local and federal law enforcement, the seven immigrants who were able to make bail before those agents arrived went free. The one who could not make bail in time, a 33-year-old roofer and father of five, has been in federal detention in Pennsylvania ever since.

"I took an oath to protect the people of this county, and that means enforcing the laws of the land," said Donald B. Smith, the Putnam County sheriff. "We have a situation in our country where our borders are not being adequately protected, and that leaves law enforcement people like us in a very difficult situation."

Other local law enforcement officials expressed similar frustration at the apparent inability of the federal government to stem the rise in illegal immigration. It is a frustration they say has been growing in the last few years, and is now reaching a point of crisis.

During that time, a number of coinciding trends may have added to the sense that there has been a breach in the covenant between the local and federal authorities, according to interviews with immigration officials, police and advocates. These trends include a housing boom that attracted growing numbers of illegal workers, especially to distant suburbs and exurbs, where federal resources are especially thin; an apparent stagnation in the size of the federal immigration police force, which has remained at about 2,000 for several years; and increasing local opposition to illegal immigration, again, especially in the suburbs.

George A. Terezakis, a Long Island immigration lawyer, said that in his practice, he had seen a trend. "The heat is definitely getting turned up. Not just on criminals, but against people I would consider charged with relatively minor offenses: Having an invalid driver's license, a fake Social Security card. A person with a job and a family can end up sitting in jail for months, and then being deported."

Federal statistics do not measure the number of immigration arrests and deportations that occur because of local intervention. Officials with the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency said the roughly 160,000 illegal immigrants deported last year represented a 10 percent increase over the year before — and a national record — but they could not say how many had been referred by the local authorities.

Until fairly recently, it was viewed as inappropriate, even unconstitutional, for the local or state authorities to be involved in the enforcement of federal law. In Los Angeles, the police still operate under an internal rule that says "undocumented alien status is not a matter for police enforcement." Similar policies apply in San Francisco and New York City.

But that may be changing, partly because the local authorities have decided to play a more active role and partly because of an unabashed call from the federal government seeking help from states and localities. Skip to next paragraph Enlarge

"The untold story of immigration law is that there are just not enough federal immigration officers to enforce the immigration laws we have," said Kris W. Kobach, a law professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City who as a counsel in the Justice Department worked on several cooperative agreements with state and local law enforcement agencies.

"The only way our programs can work is with help from local law enforcement, and we're expecting to see that happening more and more," he said.

|

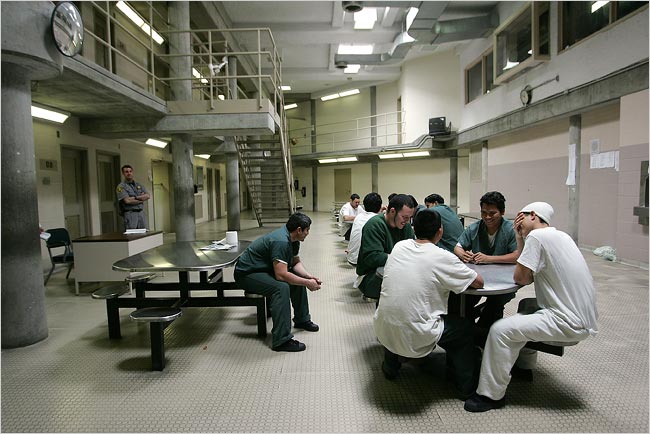

Ruth Fremson for The New York Times |

| Sheriff's deputies in Suffolk County are responsible for tracking down illegal immigrants in custody at the county jail in River-Head, NY. It is one of many counties trying to stem the rise in illegal immigration. |

To make that happen, law enforcement officials have increasingly been looking to a federal statute, the 1996 Immigration and Nationality Act. It allows the local and state authorities to reach agreements with the federal immigration and customs agency to train their officers — in a four-week crash course — to be virtual immigration agents, able to conduct citizenship investigations and begin deportation proceedings against illegal immigrants.

The law went nearly untried in its first five years on the books. Then Florida had 60 state agents and highway officers trained in 2002, and Alabama did the same for about 40 state troopers in 2003. In the next two years, the Arizona corrections department and the Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties in California each had a few dozen officers trained.

Indicating a new sense of urgency, though, 11 additional state and county jurisdictions have applied to enter the program in the past year alone, according to a spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Michael W. Gilhooly. He would not specify which they were, but public officials in Missouri, Tennessee, Arizona and about a dozen additional counties in California, Texas and North Carolina have publicly expressed interest in the program.

Local officials involved in these initiatives say they are mainly targeting hardened criminals in the immigrant population — people like gang members and sexual predators who have been the recent target of sweeps by federal immigration agents.

But many of those affected by the new home-grown vigilance are immigrants arrested for minor traffic violations, or charged with unlicensed driving, possession of forged green cards and other offenses that are virtually synonymous with the undocumented life, say immigrant advocates and lawyers.

In Springfield, Mo., for example, a furor erupted recently when a star player on the high school soccer team, Tobias Zuniga, was arrested and jailed after a routine traffic stop because he admitted to the officer that he was an illegal immigrant. Officers at the Christian County Jail notified immigration agents, and Mr. Zuniga, an 18-year-old senior, was held for a weekend before being released on bail.

"He was stopped for having excessively tinted windows," Tom Parker, the father of a friend and classmate of Mr. Zuniga, said in a telephone interview. "And he spent three nights in jail with drug dealers." Mr. Zuniga faces deportation hearings this month.

Federal immigration officials, however, maintain that the vast majority of illegal immigrants detained and deported are people convicted or charged with serious crimes. There are simply not enough immigration agents to respond every time a suspected illegal immigrant is arrested for driving with an invalid license, said Marc Raimondi, a spokesman for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

Daniel W. Beck, the sheriff of Allen County, Ohio, 100 miles northwest of Columbus, said calling immigration agents is no guarantee of action. "When people drive without licenses, when they are in this country illegally, it's really a right and wrong issue. I will arrest them," Mr. Beck said. "Unfortunately, by the time a federal agent gets here, they are sometimes already bailed out of jail." But Marianne Yang, director of the Immigrant Defense Project of the New York State Defenders Association, a lawyers' group, said a recurring problem for immigrants, legal and illegal, is the high bail set for them if they are arrested, no matter how minor the crime.

"What we see in the increasing collaboration between local authorities and I.C.E. is situations where a person would normally be released in his own recognizance, and instead is held on high bail," she said of the agreements with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

The arrests of the men playing soccer in Putnam County in January might illustrate that phenomenon. Sheriff's deputies went there in response to a complaint about safety by the administrator of the elementary school, which was in session as the men played.

Mr. Smith, the Putnam sheriff, said deputies arrested the men that day only after they refused the school administrator's request for them to leave. They were charged with criminal trespass, a class B misdemeanor, and a Brewster village judge set bail at $1,000 for seven of the eight. Bail for the eighth man, Juan Jimeniz, a roofer, was set at $3,000 because he was not able to provide his home address.

Mr. Smith said federal immigration agents were called to the jail because deputies suspected the men were illegal immigrants and "because we are trying to uphold the law for the citizens of this county."

When they arrived, seven of the men had made bail and Mr. Jimeniz, who was not able to pay his bail, was taken by the immigration agents to a federal detention wing of the Pike County Jail in Hawley, Pa., where he has remained since, fighting deportation.

"He has no criminal record," said Vanessa Merton, director of the Immigration Justice Clinic of the Pace University Law School, which represents Mr. Jimeniz. "He is a roofer. He is supporting five children."

"There is no way you could describe his detention as anything but haphazard, random and completely arbitrary," she said.

Mr. Kobach, the former Justice Department official, said "unevenness has been endemic to the nature of immigration enforcement in recent years."

But efforts by local and state authorities to pursue illegal immigrants, he said, are at least in part, "an effort to deal with that unevenness."

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Friday, April 14, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |