| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted April 10, 2004 |

Patching History: A Giant Who's Who of Black America |

|

|

||

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries |

©Bettmann/Corbis |

||

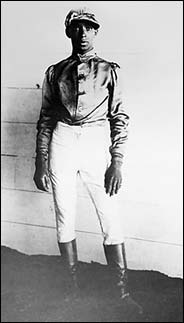

| Anna Julia Cooper (1856-1964) was an educator and writer who spent most of her life fighting for education and civil rights on behalf of women and blacks. She graduated from Oberlin College in 1884, making her one of the first African-American women to earn a bachelor's degree. In 1892 she wrote "A Voice From the South," an essay collection widely acknowledged as the first black feminist treatise. | Isaac Murphy (1861-1896), a jockey born on a farm near Frankfort, Ky., has been mostly lost to history, but he was perhaps the most influential African-American athlete of the 19th century. His long string of triumphs at the racetrack included three Kentucky Derby victories, he also won the first American Derby, in Chicago. His career began to unravel when he was charged with drunkness during an 1890 race, and he was forced to retire in 1895. |

By FELICIA R. LEE |

Tere are so many untold stories. Mary Elizabeth Bowser was a former slave who worked as a maid in the household of the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, was a spy for the Union. Onesimus, the former slave of the New England theologian Cotton Mather, came up with the idea in 1716 of deliberately infecting healthy people with the smallpox virus to combat the disease. Otabenga, born around 1883 in what was then the Belgian Congo, was lured to America, where in 1906 he found himself on display at the Bronx Zoo; in 1916 he quietly committed suicide.

These and hundreds of other stories are being assembled by two Harvard scholars for what they are calling the largest-ever collection of biographies of African-Americans. It is an ambitious effort to patch the spotty historical record about the men and women who, among other things, fled slavery, created art and shepherded civil rights campaigns in the shadow of giants like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The African American National Biography project is to be published in several volumes and there will also be an online database with about 11,000 names of the living and the dead. In another departure from conventional biographies, nominations for inclusion can be made by anyone offering a name to help enrich the narrative about race in America.

The project's first effort, "African American Lives" (Oxford University Press, 2004), is to be published this month. The online database and eight or so volumes of the biography will be available in another two or three years.

"This will revolutionize access to the black past," said Henry Louis Gates Jr., director of the W. E. B. DuBois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard. He and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a professor of history and African and African-American Studies at Harvard, are the project's editors.

"If you ask `were there black explorers?,' you can go to that category and get information," Mr. Gates said. "Black cowboys? They are there, too."

Some scholars, though, are uncomfortable with the idea of separate historical accounts, whether of women, Latinos or Jews.

"I've always felt that the separation of the African-American story from the American story was tragic," said Shelby Steele, a research fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution at Stanford who has written widely about race and culture. "You're subscribing to the original crime to solve the damage done by the crime."

Mr. Gates responds that the black database is an interim measure to correct a fragmented historical record. The number of blacks in standard biographical compilations like the "American National Biography" often represents no more than their percentage in the population, he adds, so it is inevitable that a black biography will use different criteria to judge who is worthy of inclusion.

But Mr. Steele is not satisfied with that answer. "My feeling is that what they're calling an interim move has the effect of further isolating people from mainstream history," he said.

Mr. Gates said that since publishing "Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience" in 1999, he had received dozens of letters from readers about blacks they thought deserved recognition. To keep those names coming, advertisements for the project will go in scholarly journals and general-interest magazines aimed at African-Americans, like Jet and Ebony, as well as on Oxford University Press's Web site, www.oup.com/us/africanamericanlives.

"There is so much that is needed to be done in African-American scholarship still," Ms. Higginbotham said. "Just this year, three biographies were published on Harriet Tubman alone. Before that it was mostly juvenile-level biographies. In almost any city you can go to black neighborhoods and see schools named for local black heroes and you have no idea who those people are."

Everyone knows Fannie Lou Hamer, she says, but few know names like Isola Richardson, a maid in Kansas City, Mo., who was one of of the leaders of the black Baptist church movement and the local Y.W.C.A.

"African American Lives" is a kind of greatest hits, Mr. Gates said. It will include 600 entries (some with more than one name), from Henry Box Brown, a 19th-century former slave who mailed himself north to freedom, to Emmett Till, the 14-year-old murdered by whites in the Mississippi Delta in 1955 for supposedly whistling at a white woman. The project's editorial and advisory boards, which include scholars like David Levering Lewis, who won two Pulitzer Prizes for his two-part biography of W. E. B. DuBois, will decide which candidates merit inclusion.

"This is a major publishing event, absolutely," said Leon F. Litwack, a Pulitzer Prize-winning professor of American history at the University of California, Berkeley. "What we're dealing with is a field that became a field only since the 1960's, in the sense of being an academic field with textbooks. It was consistent with a conception of history that defined black people out of American identity."

Mr. Litwack recalled visiting New York's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the 1950's and finding it nearly empty, though now places like it are much used. Mr. Litwack also asks his students to sift through major oral history archives, like those at Duke and Southern Mississippi University, to keep up with all the new research.

Mr. Gates said he and Ms. Higginbotham had sold Oxford on the idea of a separate African-American biography project because the documenting of black history is virtually in its infancy. And as racial barriers continue to fall, many significant black achievers are still living, people like the Black Entertainment Television founder Robert L. Johnson, Secretary of State Colin Powell and the media giant Oprah Winfrey, Mr. Gates said. Some of the more important entries will eventually end up in the "American National Biography."

What the impact will be is an open question. John McWhorter, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute and the author of "Authentically Black: Essays for the Black Silent Majority" (Gotham Books, 2003), wonders what effect inspiring or even tragic African-American stories from the past have on blacks today.

"I think that in our times there's an unfortunate tendency for many African-Americans to see the most urgent part of our history as the tragedies," he said. "I worry that in our current climate stories about Benjamin Banneker and Mary McLeod Bethune cannot be inspiring," he said, referring to the 18th-century African-American mathematician and the 19th-century black educator, "when so often we're told that the `blackest person' is 50 Cent."

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Arts & Ideas, of Saturday, April 10, 2004.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |