| Want to send this page or a link to a

friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

|

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES |

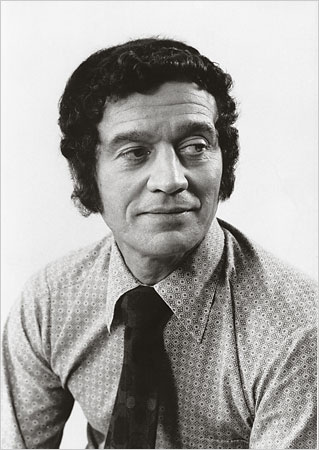

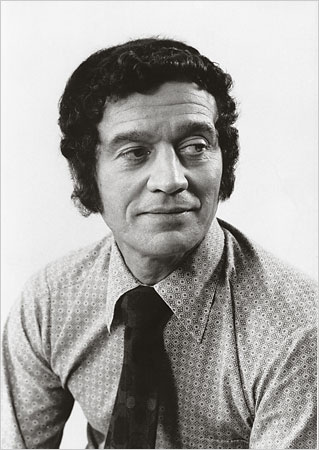

| Anatole Broyard, 1971 |

| _________________________ |

| Illustrated. 514pp. Little |

| _________________________ |

IN 1855, Henry Broyard, a

young white New Orleans carpenter, decided to pass as black in order to be legally

entitled to marry Marie Pauline Bonée, the well-educated daughter of colored refugees

from Haiti, who was about to have his child; their marriage license describes them both as

“free people of color.” A century and a half later, their

great-great-granddaughter, Bliss Broyard, who had been raised as white, abruptly found

herself confronting the implications of her newly discovered black identity.

The daughter of the writer and New York Times book critic Anatole Broyard, she had

grown up with a feeling “that there was something about my family, or even many

things, that I didn’t know.” What was lacking was any real sense of the history

of the father she adored or any contact with his relatives, apart from one dimly

remembered day in the past when her paternal grandmother had once visited them in their

18th-century house in the white enclave of Southport, Conn. Even in the last weeks of his

life, the secret Anatole Broyard had kept from Bliss and her brother, Todd, was one he

could not bear to reveal himself; it was their mother who finally told them, “Your

father’s part black,” not long before Broyard died of prostate cancer.

Their reaction would have stunned their father. “That’s all?” Todd said.

For 24-year-old Bliss, the news was thrilling, “as though I’d been reading a

fascinating history book and then discovered my own name in the index. I felt like I

mattered in a way that I hadn’t before.”

The year was 1990. Profound changes in attitudes about race in America had occurred

since 1947, when Anatole Broyard, who during the war had been the white officer in charge

of a regiment of black stevedores, left his parents and sisters behind him in

Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, having made up his mind to continue to pass as white in the

bohemian milieu of Greenwich Village. Because of his charm, carefully honed conversational

brilliance and success in seducing one impressionable young woman after another, the

circles of hipster intellectuals he moved in would have accepted him whatever he called

himself — and did whenever he selectively revealed the truth. But Broyard, less

hipster and existentialist than an innately conservative young man ambitious to become

part of the literary establishment (then exemplified by The Partisan Review), justified

the choice he’d made by refusing to have any limits put on his freedom or to be

tagged as a black writer like James Baldwin.

In one way, he wasn’t wrong at all. “My father truly believed,” Bliss

Broyard writes in “One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life — a Story of Race and

Family Secrets,” “that there wasn’t any essential difference between blacks

and whites and that the only person responsible for determining who he was supposed to be

was himself.” But for Broyard to construct a white identity required the ruthless and

cowardly jettisoning of his black family. He would later lamely tell his children that

their grandmother and their two aunts, one of them with tell-tale dark skin, simply

didn’t interest him. During the 1960s, he expressed no sympathy for the civil rights

movement, opposed, his daughter writes, to a movement that required “adherence to a

group platform rather than to one’s ‘essential spirit.’ ” His

posthumously published memoir, “Kafka Was the Rage,” revealed only that his

people were from New Orleans.

Broyard first made the pages of The Partisan Review with a much-discussed 1948 essay on

the black roots of hipsterism. Two short stories, one about a father’s death, won him

a contract for a much anticipated autobiographical novel he was never able to complete.

Paradoxically, his unintended legacy to his daughter would be the huge story he could

never have dealt with: the 250-year history of the New Orleans Broyards culminating in the

riddle of his own life. In the process of piecing it together, Bliss Broyard would have to

cleanse herself of the assumptions about racial inferiority that had been ingrained in

her. Without losing her deep love for her father, she would have to scrutinize his life

with a historian’s objectivity. Contacting lost relatives scattered from New Orleans

to Los Angeles, she would gradually fit herself back into the enormous extended family

whose very existence had been concealed from her and meet distant cousins who

matter-of-factly considered themselves white without losing touch with the Broyards of

color.

What am I?” was the initial question she began asking herself as she started

looking up the many definitions of “creole.” Until she found that her black

ancestors were free people of color, she was convinced that she must be the direct

descendant of slaves. Her own black genetic inheritance went only as far back as the birth

of Henry Broyard’s son Paul in 1856. Black by choice, Henry Broyard joined a militia

unit of colored men to defend New Orleans against the Yankee invasion in 1861; the

following year, after New Orleans fell to the Union troops, he entered the first black

regiment in the history of the United States Army. He endured the humiliating treatment of

black soldiers and fought in the Battle of Port Hudson. He died as a white man in 1873,

during a brief period when a “reformed Southern society” seemed

“tantalizingly within reach,” but was buried in a colored section of St. Louis

Cemetery. His son Paul, a leading member of the Creole community in New Orleans, would

prosper as a carpenter and builder and serve as the Republican president of the Fifth Ward

during the 1890s. He played an active role in the fight against the resurgence of white

supremacy until he lost heart as Jim Crow legislation stripped away the gains blacks had

won during Reconstruction. Bliss Broyard’s grandfather, Nat, would give up on his

segregated birthplace in 1927 and move his family north to New York, where he at times had

to pass as white in order to get work and always felt like an embittered exile. His son,

Anatole, the most prominent of the Broyards, was perhaps the one most warped by racism.

For Henry Broyard, race was nothing measurable in drops of blood — it was composed

of a name and the restrictive laws and attitudes of society. “I may never be able to

answer the question What am I?” his great-great-granddaughter writes, “yet the

fault lies not in me but with the question itself.” Her brave, uncompromising and

powerful book is an important contribution toward the negation of that question.

Joyce Johnson is the author of the memoirs “Minor Characters” and

“Missing Men.”

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book

Review, of Sunday, October 21, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of

democracy and human rights |