| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted December18, 2005 |

|

|||

| New World Economy | |||

|

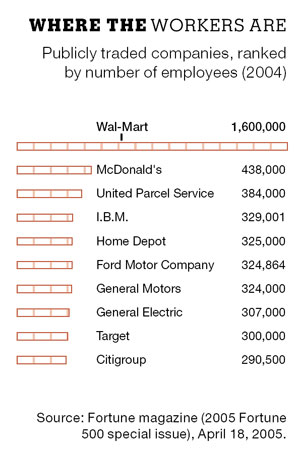

In recent weeks, looking toward next year's midterm elections, leaders of both parties have engaged in highly charged arguments about withdrawal from Iraq, Medicaid shortfalls and allegations of Republican corruption. Anyone bothering to peruse the rest of the front page, however, might have noticed a few items that seemed tangentially related, but that, together, tell a story that is far more consequential for the next 50 years of American life. First, just before Thanksgiving, General Motors, buckling under the weight of $2 billion in losses, announced that it now planned to lay off 30,000 workers and scale back or close a dozen plants. A few days later, at the traditional commencement of the holiday season, thousands of American consumers began lining up in the dark hours of morning to be among the first to pile into Wal-Mart, hoping to re-emerge with discounted laptops and Xboxes under their arms. Wal-Mart has now inherited G.M.'s mantle as the largest employer in the United States, which is why these snapshots of two corporations, taken in a single week, say more about America's economic trajectory than any truckload of spreadsheets ever could.

G.M., of course, was the very prototype of 20th-century bigness, the flagship company for a time when corporate power was vested in the hands of a small number of industrial-era institutions. There is no question that rising labor costs hurt G.M., but that obscures the larger point of the company's decline; caught in the last century's mind-set, it has often been unable or unwilling to let consumers drive its designs, as opposed to the other way around. Must the company keep making Buicks and Pontiacs until the end of days, even as they recede into American lore? Many of the workers G.M. decided to lay off last month were its best and most productive. Their bosses simply couldn't give them a car to build that Americans really wanted to buy.

|

As it happens, G.M.'s inability to adapt offers some perspective on our political process, too. Democrats in particular, architects of the finest legislation of the industrial age, have approached the global economy with the same inflexibility, at least since Bill Clinton left the scene. Just as G.M. has protected its outdated products at the expense of its larger mission, so, too, have Democrats become more attached to their programs than to the principles that made them vibrant in the first place. So what if Social Security and Medicaid functioned best in a world where most workers had company pensions and health insurance and spent their entire careers with one employer? The mere suggestion that these programs might be updated for a new, more consumer-driven economy sends Democratic leaders into fits of apoplexy.

While G.M. rusts away like some relic from the last century, Wal-Mart beckons us toward our shrink-wrapped and discounted future. Wal-Mart's founding family is said to be wealthier than Bill Gates and Warren Buffet combined, and yet more than half of the company's employees don't receive health care, and its enduring quest to bring us lower prices drives down wages everywhere. Here we have the model for globalization as Republicans envision it - a world in which rugged entrepreneurialism is overly romanticized and the unskilled expendable, and where shareholder profits are the only measure of success. Republicans have embraced the future of the global marketplace, but to them the future looks a lot like "Road Warrior."

The debate over Wal-Mart centers on whether it is, on the whole, good or not so good. Jason Furman, a Democratic policy expert, has prepared a persuasive report for the Center for American Progress in which he notes that Americans may have saved as much as $263 billion last year - that's $2,329 per household - by shopping at Wal-Mart, which amounts to the equivalent of a massive tax break. This argument over Wal-Mart's virtue or villainy is interesting but ultimately academic; it is like having had an argument, at the dawn of the microchip, about the merits of automation. The service economy is a reality of our time, and it would be wishful to expect that its engine can sustain the middle class in the way that industry once did. Wal-Mart didn't ask to be the new G.M., and even if it wanted to treat its employees as generously, it couldn't; Furman concludes that Wal-Mart's profits would be obliterated by adopting companywide health care or a significant raise in wages. It makes little sense to blame one company for the pain caused by a profound economic transformation.

What would be more constructive, probably, is a total reimagination of the basic contract between government, businesses and workers - a process that Clinton tentatively put in motion but that has since stalled as both parties retreated from the vexing challenges of globalization. After all, if you were going to sit down and create a system for our time, it probably wouldn't look much like the one we have. Does it make sense to expect businesses to finance lavish health care plans when foreign competition is forcing companies to cut their costs? Isn't government better equipped to insure a nomadic work force while employers take on the more manageable task of childcare - a problem that hardly existed 50 years ago? If government were to remove the burden of health care costs from businesses, enabling them to better compete, wouldn't it then be more reasonable to create disincentives for employers who are thinking of shipping their jobs overseas? Isn't the very notion of a payroll tax for workers antiquated and inequitable in a society where so many Americans earn stock dividends and where a growing number are self-employed? If they were to spend more time debating these and other longer-term questions, our politicians might have some small hope of leaving a legacy to match their predecessors' - a legacy better than the choice between the New Deal and no deal at all.

Matt Bai, who covers national politics for the magazine, is working on a book about the Democratic Party. Next

Copyright 2005The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times Magazine of Sunday, December 18, 2005.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |