| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| More Books and Arts |

| Posted February 3, 2008 |

Hello, Neighbor |

|

|

|

GREGG NEWTON/CORBIS |

|

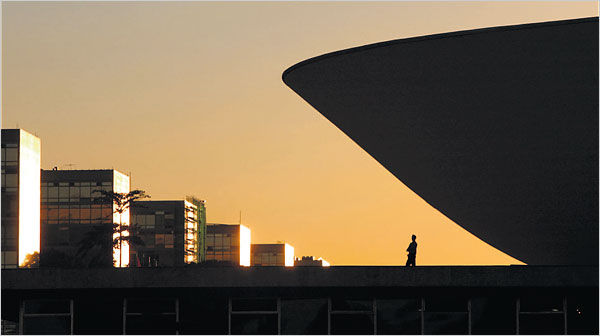

| Brazil's capital, Brasilia. The country is working to spread democracy's benefits among all social classes. |

By CAROLYN CURIEL |

ANYONE who caught Hugo Chávez’s act at the United Nations in September 2006 — in which Chávez, the president of Venezuela, compared George W. Bush to Satan — might infer that relations between Latin America and the United States have gone to hell. But Chávez’s extreme theatrics mask the real problem. Our mostly Spanish-speaking neighbors have reason to suspect that except for occasional military and economic interventions, American leaders don’t pay them much mind, let alone give them the respect they’ve earned.

| FORGOTTEN CONTINENT |

| The Battle for Latin America's Soul |

| By Michael Reid |

| Illustrated. 384 pp. |

| Yale University Press. $30. |

President Ronald Reagan, returning from a 1982 trip to Latin America, said: “You’d be surprised. They’re all individual countries.” Richard Nixon, tutoring Donald Rumsfeld in 1971 on foreign policy, found importance in Russia and China, but noted, “People don’t give one damn about Latin America.” The myopia is not limited to Washington. In 1992, Margaret Thatcher — perhaps more familiar with the desolate Falkland Islands, which her military had reclaimed from Argentina when she was the prime minister of Britain — seemed nonplused to see skyscrapers over São Paulo, Brazil, the largest city in the Southern Hemisphere: “Why didn’t anybody tell me about this?”

For his part, President Bush, from a border state, initially instilled great expectations. Then 9/11 happened. Like Franklin D. Roosevelt, who seemed to acknowledge Latin America’s significance until the attack on Pearl Harbor, Bush settled for the false sense of partnership that comes from proximity.

Michael Reid, a longtime Latin America correspondent and the editor of the fine Americas section of The Economist, takes exception to such benign neglect, and worse, in “Forgotten Continent: The Battle for Latin America’s Soul.” In a brilliantly researched and annotated work of scholarship, Reid makes a cogent case that the battle has become more internal — but of necessity, not by choice. Since Latin American nations are beginning to get their true democratic bearings, he argues, now would be a good time for old hands at stable democracy — particularly in Washington and Europe — to come off the bench and enter the game. The consequence of not doing so would be to forfeit this critical relationship to China and India, both eager to assert themselves, at least economically, in the region.

Latin America has undergone dramatic change since 1977, when all but four countries were dictatorships. Today, with the exception of Cuba, each has evolved into a democracy — though sometimes the results have been so flawed that, like Barry Bonds and his home run record, they require an asterisk, to explain that the leader was elected but under less than ideal circumstances. These include constitutional rewrites to perpetuate power (notably in the cases of Chávez and Alberto Fujimori of Peru) and large-scale fraud (Mexico, for decades, in every charade of an election under the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI). There are exceptions. Costa Rica, one of the world’s sturdier democracies, offers valuable — although not always readily applicable — lessons in democracy building through demilitarization, selective development, expansive education and a free press. Unfortunately, Reid does not dwell much on it.

As an outsider with a keen inside view, however, he performs an important service, outlining the historical record and a prognosis. Reid has no ideological ax to grind, chiding both the left and the right for treating the region with “the utmost condescension.” He carefully documents little-known or -remembered American missteps, including zealous anti-Communist interventions that ousted elected leaders, like Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala during the early years of the cold war, a move that set back the cause of democracy. At the same time, though, he advises against wallowing in defeatist blame games.

The right approach for the United States involves a commitment to fostering cooperation, particularly on the economic front, emphasizing free trade and offering Latin nations support for building democratic institutions. Latin American hopes for the beginnings of just such a partnership with Washington were prematurely lifted when President Bill Clinton organized the first Summit of the Americas in 1994, vowing to work toward the Free Trade Area of the Americas, as an extension of the North American Free Trade Agreement. That never materialized, and bilateral agreements, most recently with Peru, have been slow in coming. Reid works especially hard to make the case for a pact with Colombia, which has so far not satisfied human rights concerns from monitors and in Congress.

He is an admirer of the Washington Consensus, a mix of fiscal austerity, privatization and market liberalization intended to fix the widespread debt crises and hyperinflation of the 1980s. Economies did become steady, though tenuously in many instances. Reid sees that the remedy was incomplete: “Perhaps the most important missing commitment was to equity, to slashing poverty and inequality.” He believes such gaps, with help, are not insurmountable. Considering how far much of Latin America has come in recent decades, overcoming civil wars, mass murders, dictatorships and military juntas, he may turn out to be right.

Reid tirelessly seeks out signs of progress, but there’s no escaping that tens of millions of people still live in abject poverty. He correctly faults the legacy of the brutal conquest of an indigenous population many times larger than that north of Mexico. Pervasive racism impedes darker-skinned people, including not only descendants of the Aztec, Incan and Mayan civilizations but also the millions whose ancestors were brought enslaved from Africa. Divisions have been perpetuated by the failure to achieve land reform. The resulting migration, legal and not, has drained nations of their strongest and potentially brightest, who nonetheless often receive a cold welcome in the North. The separation of families has taken a toll, offset somewhat by tens of billions of dollars in cash remittances that buoy economies.

The most acute disparities have given rise to leaders like Chávez and President Evo Morales of Bolivia, who pander to the downtrodden but whose policies can scare off the foreign investment needed to provide jobs. In an argument that could be lifted wholesale into the American presidential campaign playbook, Reid maintains that populists, powered more by charisma than by meaningful experience or constructive ideas, constitute a dangerous trend. Yet Chávez’s recent defeat at the polls, as he sought permission to be president for life, was reassuring.

The good things Latin American governments are doing to keep their people home usually go unreported. Some countries have tried to spread the benefits of democracy to every social class. As Reid points out, while the United States has backed away from affirmative action, Brazil has used it to integrate the courts and universities. Under President Ernesto Zedillo, Mexico began experimenting with ways to alleviate poverty. President Vicente Fox built on the program, known as Oportunidades, which offers some five million families incentives for doing the right thing, like keeping children in school. The results, including improved graduation rates, prompted Mayor Michael Bloomberg to attempt a similar program in New York.

On its own, Latin America has made undeniable strides, slowly and surely. Michael Reid urges the naysayers to liberate their thinking and perhaps also an unfairly disregarded part of the world. Carolyn Curiel, a member of the editorial board of The Times, previously served as United States ambassador to Belize.

Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Book Review, of Sunday, February 3, 2008.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |