|

| Want to send this page or a link to a

friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

Languages

Die, but Not Their Last Words |

|

|

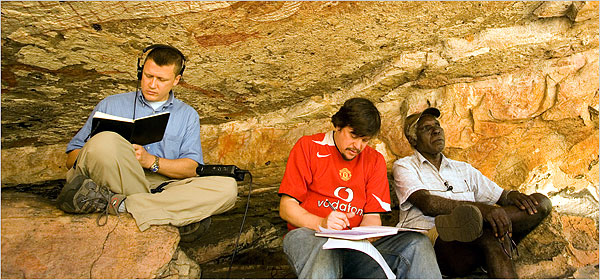

Cris Rainier/National Geographic |

| Charlie Muldunga, right, the last known speaker of Amurdag, with two

researchers who are making a record of dying languages, K. David Harrison, left, and

Gregory D..S. Anderson.. |

Of the estimated 7,000 languages spoken in the world today, linguists say, nearly half

are in danger of extinction and likely to disappear in this century. In fact, one falls

out of use about every two weeks.

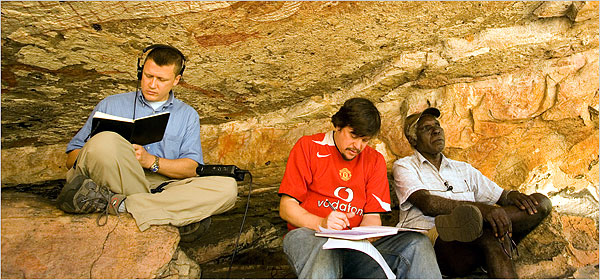

Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages In Bolivia, Ilaryon Ramos Condori

knows a secret tongue that is used mainly for preserving knowledge of medicinal plants.

Some languages vanish in an instant, at the death of the sole surviving speaker. Others

are lost gradually in bilingual cultures, as indigenous tongues are overwhelmed by the

dominant language at school, in the marketplace and on television.

New research, reported yesterday, has found the five regions where languages are

disappearing most rapidly: northern Australia, central South America, North America’s

upper Pacific coastal zone, eastern Siberia, and Oklahoma and the southwestern United

States. All have indigenous people speaking diverse languages, in falling numbers.

|

| Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages |

| In Bolivia, Ilaryon Ramos Condori knows a secret tongue that is used

mainly for preserving knowledge of medicinal plants. |

The study was based on field research and data analysis supported by the National

Geographic Society and the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. The findings

are described in the October issue of National Geographic and at languagehotspots.org. In

a teleconference with reporters yesterday, K. David Harrison, an associate professor of

linguistics at Swarthmore, said that more than half the languages had no written form and

were “vulnerable to loss and being forgotten.” Their loss leaves no dictionary,

no text, no record of the accumulated knowledge and history of a vanished culture.

Beginning what is expected to be a long-term project to identify and record endangered

languages, Dr. Harrison has traveled to many parts of the world with Gregory D. S.

Anderson, director of the Living Tongues Institute, in Salem, Ore., and Chris Rainier, a

filmmaker with the National Geographic Society.

The researchers, focusing on distinct oral languages, not dialects, interviewed and

made recordings of the few remaining speakers of a language and collected basic word

lists. The individual projects, some lasting three to four years, involve hundreds of

hours of recording speech, developing grammars and preparing children’s readers in

the obscure language. The research has concentrated on preserving entire language

families.

In Australia, where nearly all the 231 spoken tongues are endangered, the researchers

came upon three known speakers of Magati Ke in the Northern Territory, and three Yawuru

speakers in Western Australia. In July, Dr. Anderson said, they met the sole speaker of

Amurdag, a language in the Northern Territory that had been declared extinct.

“This is probably one language that cannot be brought back, but at least we made a

record of it,” Dr. Anderson said, noting that the Aborigine who spoke it strained to

recall words he had heard from his father, now dead.

Many of the 113 languages in the region from the Andes Mountains into the Amazon basin

are poorly known and are giving way to Spanish or Portuguese, or in a few cases, a more

dominant indigenous language. In this area, for example, a group known as the Kallawaya

use Spanish or Quechua in daily life, but also have a secret tongue mainly for preserving

knowledge of medicinal plants, some previously unknown to science.

“How and why this language has survived for more than 400 years, while being

spoken by very few, is a mystery,” Dr. Harrison said in a news release.

The dominance of English threatens the survival of the 54 indigenous languages in the

Northwest Pacific plateau, a region including British Columbia, Washington and Oregon.

Only one person remains who knows Siletz Dee-ni, the last of many languages once spoken on

a reservation in Oregon.

In eastern Siberia, the researchers said, government policies have forced speakers of

minority languages to use the national and regional languages, like Russian or Sakha.

Forty languages are still spoken in Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico, many of them

originally used by Indian tribes and others introduced by Eastern tribes that were forced

to resettle on reservations, mainly in Oklahoma. Several of the languages are moribund.

Another measure of the threat to many relatively unknown languages, Dr. Harrison said,

is that 83 languages with “global” influence are spoken and written by 80

percent of the world population. Most of the others face extinction at a rate, the

researchers said, that exceeds that of birds, mammals, fish and plants.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, Science,

of Wednesday, September 19, 2007.

| Wehaitians.com, the

scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |