| Want to send this page or a link to a friend? Click on mail at the top of this window. |

| Posted April 17, 2006 |

It's a Complicated Dance Between Strong Leadership and the Popular Will |

|

Alexander Gardner |

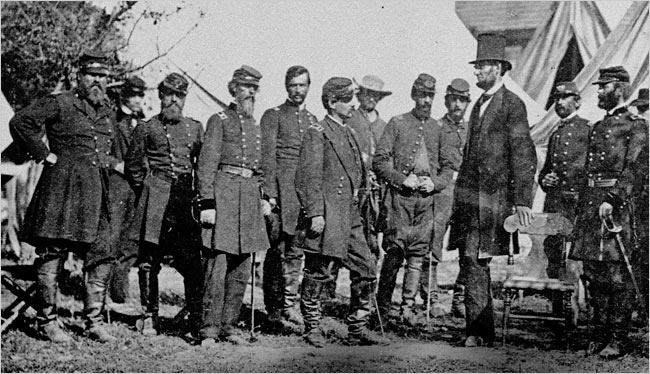

| Drawing the line between demagoguery and leadership: above, Lincoln at Antietam, Md., during the Civil War; while a defender of the Constitution, he suspended habeas corpus. |

| __________________________ | |

By EWARD ROTHSTEIN |

|

| __________________________ |

Be careful what you wish for, particularly when it comes to politics. Wish for democratic elections, and you may get duly elected tyranny and terror. Wish for democratic debate, and you may get polarized parties and a divided electorate. Wish for democratic responsiveness and you may get opinion-poll leadership. Wish for statesmanship and you may get demagoguery. One temptation might be to wish for nothing in particular, but then who knows what might happen?

The difficulty seems to congeal around the very nature of political leadership in a democratic state. A democratic leader is, at least in part, an oxymoron. A leader is ahead of those being led, but a democratic leader is also supposed to be a follower, obeying the will of the people.

Neither position is without dangers. Given examples of perverse expressions of popular will — the terrors of the French Revolution, Nazism, Hamas — who can simply rely on democratic sentiment? And given similar examples of demagoguery, who can believe in an enlightened tyranny? We desire strong leaders and justly fear them. We desire widespread democracy and justly worry about the consequences.

Such issues — as relevant in the United States and Europe as in Iraq — inspired a conference at Yale University earlier this month, organized by the political scientist Steven Smith with a colleague, Bryan Garsten: "Statesmen and Demagogues: Democratic Leadership in Political Thought." The conference was also a reflection of Mr. Smith's belief that in the academic world questions about the nature of political leadership are not as fully explored as they should be.

This is partly a result of a long trend, he said, in which politics has been treated as the reflection of supposedly more profound economic or historical forces. But understanding the nature of statesmanship, he suggested, also requires thinking about the powers of remarkable individuals. This subject, often treated in popular biography, is much neglected in recent political science, in Mr. Smith's view.

So the conference came at the subject from differing perspectives, bringing together historians, students of contemporary politics and political philosophers. The speakers ranged from the French political scientist Pierre Hassner to Carnes Lord, who teaches military strategy at the United States Naval War College.

What happens, for example, in developing countries where democracy and demagoguery vie for power (a subject addressed by Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the former president of Brazil now teaching at Brown University)? When did our ideas of demagoguery and leadership arise (a subject considered by Melissa Lane of Cambridge University, who spoke about notions of the demagogue in Plato and Plutarch)?

|

| Tropical Press Agency/Hulton Archive - Getty Images |

| Hitler at a rally in Nurember in 1938; by some definitions he was not a demagogue because he sincerely believed his theories. |

And how do examples of admired political leadership differ from examples of tyranny or demagoguery? Simple formulas will not suffice. After all, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War, yet is credited with preserving the Constitution. Hitler is often described as a demagogue who spread theories about Jewish conspiracies to mobilize popular support, yet, as the historian Jeffrey Herf argued, this wasn't pure demagoguery: Hitler really believed these theories. "A statesman," declared Harry S. Truman in a comment cited more than once during the two days of talks, "is a politician who's been dead 10 or 15 years." So is it simply a matter of political taste? Is one man's statesman another man's demagogue?

____________ |

|

Measuring the health of a democracy not by its tidiness, but by its tensile strength. |

|

____________ |

This much became clear: There is more to it than that.

Participants were all given a copy of Lincoln's 1838 Lyceum speech to read, in which the future president condemned mob violence and racial lynching but also considered the tension between a constitutional order and ambitious individuals who seek to transcend its restrictions. Such challengers, Lincoln wrote, aspire to greatness, and seem to come "from the family of the lion or the tribe of the eagle." How does a democratic order contain such ambition, and how can such ambition find satisfaction in democratic statesmanship?

This is not an incidental tension in democratic political life: it may be the essential one, defining democracy's risks and possibilities. Jeffrey Tulis, who teaches government at the University of Texas at Austin, suggested that powerful political leadership almost always contains within itself a challenge to democracy; it asserts prerogatives; it takes liberties. It even emerges most clearly at times when the democratic order itself is under threat (think of Lincoln, Churchill or Franklin Delano Roosevelt).

Statesmanship, that is, arises at disruptive times while being potentially disruptive in itself. Yet somehow, these disruptions must be absorbed within that threatened order.

Mr. Tulis pointed out that Locke believed that political leaders, in seeking the public good, possessed the prerogative to act even against the law itself. History, though, has amply displayed the dangers of that principle. American constitutionalism, Mr. Tulis suggested, created a new kind of arena for statesmanship: the lion and eagle are tamed by checks and constitutional arrangements.

There is something sober rather than idealistic in this arrangement: it acknowledges human weakness and ambition. But it doesn't solve the problem; it only postpones it, creating obstacles for statesmanship's ambitions, demanding that, at least at times, the leader must follow.

Is this, then, the democratic proposal? It offers not the abstract principle, but the mess of common practice. It presumes the existence of disagreement and difference. Statesmanship becomes associated not with grand visions but with the practical working out of things. No wonder strong democratic leadership is so difficult to maintain and so historically rare: democracy discourages power with negotiation, argument and a continuous testing of wills.

There are dangers here, too, of course. If a society does not accept the principle of disagreement, then its leadership will not be democratic no matter what its origins. The lion and the eagle still have tremendous lure; so do attempts to cripple them. Democracy, at any rate, offers not virtue but struggle. Virtue requires something else. Connections, a critic's perspective on arts and ideas, appears every other Monday.

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, TheArts, of Monday, April 17, 2006.

| Wehaitians.com, the scholarly journal of democracy and human rights |

| More from wehaitians.com |