IF there is ever a class in how to remain calm while trapped beneath $250,000 in loans, Michael Wallerstein ought to teach it.

|

Is Law School a Losing Game? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

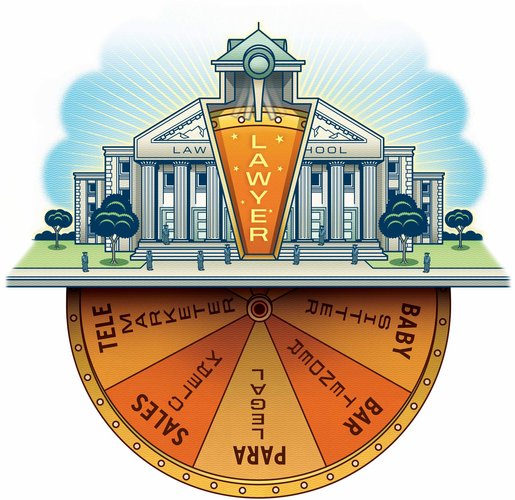

PETER AND MARIA HOEY |

|

|

By DAVID SEGAL |

Here he is, sitting one afternoon at a restaurant on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a tall, sandy-haired, 27-year-old radiating a kind of surfer-dude serenity. His secret, if that’s the right word, is to pretty much ignore all the calls and letters that he receives every day from the dozen or so creditors now hounding him for cash.

“And I don’t open the e-mail alerts with my credit score,” he adds. “I can’t look at my credit score any more.”

Mr. Wallerstein, who can’t afford to pay down interest and thus watches the outstanding loan balance grow, is in roughly the same financial hell as people who bought more home than they could afford during the real estate boom. But creditors can’t foreclose on him because he didn’t spend the money on a house.

He spent it on a law degree. And from every angle, this now looks like a catastrophic investment.

|

||

|

Well, every angle except one: the view from law schools. To judge from data that law schools collect, and which is published in the closely parsed U.S. News and World Report annual rankings, the prospects of young doctors of jurisprudence are downright rosy.

In reality, and based on every other source of information, Mr. Wallerstein and a generation of J.D.’s face the grimmest job market in decades. Since 2008, some 15,000 attorney and legal-staff jobs at large firms have vanished, according to a Northwestern Law study. Associates have been laid off, partners nudged out the door and recruitment programs have been scaled back or eliminated.

And with corporations scrutinizing their legal expenses as never before, more entry-level legal work is now outsourced to contract temporary employees, both in the United States and in countries like India. It’s common to hear lawyers fret about the sort of tectonic shift that crushed the domestic steel industry decades ago.

But improbably enough, law schools have concluded that life for newly minted grads is getting sweeter, at least by one crucial measure. In 1997, when U.S. News first published a statistic called “graduates known to be employed nine months after graduation,” law schools reported an average employment rate of 84 percent. In the most recent U.S. News rankings, 93 percent of grads were working — nearly a 10-point jump.

In the Wonderland of these statistics, a remarkable number of law school grads are not just busy — they are raking it in. Many schools, even those that have failed to break into the U.S. News top 40, state that the median starting salary of graduates in the private sector is $160,000. That seems highly unlikely, given that Harvard and Yale, at the top of the pile, list the exact same figure.

How do law schools depict a feast amid so much famine?

“Enron-type accounting standards have become the norm,” says William Henderson of Indiana University, one of many exasperated law professors who are asking the American Bar Association to overhaul the way law schools assess themselves. “Every time I look at this data, I feel dirty.”

IT is an open secret, Professor Henderson and others say, that schools finesse survey information in dozens of ways. And the survey’s guidelines, which are established not by U.S. News but by the American Bar Association, in conjunction with an organization called the National Association for Law Placement, all but invite trimming.

A law grad, for instance, counts as “employed after nine months” even if he or she has a job that doesn’t require a law degree. Waiting tables at Applebee’s? You’re employed. Stocking aisles at Home Depot? You’re working, too.

Number-fudging games are endemic, professors and deans say, because the fortunes of law schools rise and fall on rankings, with reputations and huge sums of money hanging in the balance. You may think of law schools as training grounds for new lawyers, but that is just part of it.

They are also cash cows.

Tuition at even mediocre law schools can cost up to $43,000 a year. Those huge lecture-hall classes — remember “The Paper Chase”? — keep teaching costs down. There are no labs or expensive equipment to maintain. So much money flows into law schools that law professors are among the highest paid in academia, and law schools that are part of universities often subsidize the money-losing fields of higher education.

“If you’re a law school and you add 25 kids to your class, that’s a million dollars, and you don’t even have to hire another teacher,” says Allen Tanenbaum, a lawyer in Atlanta who led the American Bar Association’s commission on the impact of the economic crisis on the profession and legal needs. “That additional income goes straight to the bottom line.”

There were fewer complaints about fudging and subsidizing when legal jobs were plentiful. But student loans have always been the financial equivalent of chronic illnesses because there is no legal way to shake them. So the glut of diplomas, the dearth of jobs and those candy-coated employment statistics have now yielded a crop of furious young lawyers who say they mortgaged their future under false pretenses. You can sample their rage, and their admonitions, on what are known as law school scam blogs, with names like Shilling Me Softly, Subprime JD and Rose Colored Glasses.

“Avoid this overpriced sewer pit as if your life depended on it,” writes the anonymous author of the blog Third Tier Reality — a reference to the second-to-bottom tier of the U.S. News rankings — in a typically scatological review. “Unless, of course, you think that you will be better off with $110k-$190k in NON-DISCHARGEABLE debt for a degree that qualifies you to wait tables at the Battery Park Bar and Lounge.”

|

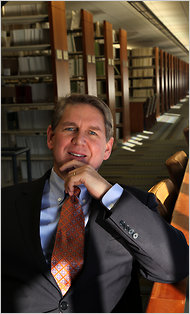

| JIM WILSON/THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| William Henderson of Indiana University says law schools have a moral obligation to tell the truth about themselves. |

Michael Wallerstein, who has a law degree, has $250,000 in loans and only the occasional job as a legal temp.

But so far, the warnings have been unheeded. Job openings for lawyers have plunged, but law schools are not dialing back enrollment. About 43,000 J.D.’s were handed out in 2009, 11 percent more than a decade earlier, and the number of law schools keeps rising — nine new ones in the last 10 years, and five more seeking approval to open in the future.

Apparently, there is no shortage of 22-year-olds who think that law school is the perfect place to wait out a lousy economy and the gasoline that fuels this system — federally backed student loans — is still widely available. But the legal market has always been obsessed with academic credentials, and today, few students except those with strong grade-point averages at top national and regional schools can expect a come-hither from a deep-pocketed firm. Nearly everyone else is in for a struggle. Which is why many law school professors privately are appalled by what they describe as a huge and continuing transfer of wealth, from students short on cash to richly salaried academics. Or perhaps this is more like a game of three-card monte, with law schools flipping the aces and a long line of eager players, most wagering borrowed cash, in a contest that few of them can win.

And all those losers can remain cash-poor for a long time. “I think the student loans that kids leave law school with are more scandalous than payday loans,” says Andrew Morriss, a law professor at the University of Alabama. “And because it’s so easy to get a student loan, law school tuition has grossly outpaced the rate of inflation for the last 20 years. It’s now astonishingly high.”

|

|

MICHAEL FALCO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES |

| Michael Wallerstein, who has a law degree, has $250,000 in loans and only the occasional job as a legal temp. |

Like everything else about the law, however, the full picture here is complicated. Independent surveys find that most law students would enroll even if they knew that only a tiny number of them would wind up with six-figure salaries. Nearly all of them, it seems, are convinced that they’re going to win the ring toss at this carnival and bring home the stuffed bear.

And many students enroll for reasons other than immediate financial returns. Mr. Wallerstein, for instance, was drawn by the prestige of the degree. He has no regrets, at least for now, even though he seems doomed to a type of indentured servitude at least through his 30s.

“Law school might not be worth it for another 10 or 15 years,” he says, “but the riskier approach always has the bigger payoff.”

True, say Professor Henderson and his allies. But he contends that law schools — which, let’s not forget, require students to take courses on disclosure and ethics — have a special moral obligation to tell the truth about themselves. It’s an obligation that persists, he says, even if students would sign on the dotted line no matter what.

“You’re beginning your legal education at an institution that is engaging in the kind of disreputable practices that we would be incredibly disappointed to discover our graduates engaging in,” he says. “What we have here is powder keg, and if law schools don’t solve this problem, there will be a day when the Federal Trade Commission, or some plaintiff’s lawyer, shows up and says ‘This looks like illegal deception.’”

WHEN he started in 2006, Michael Wallerstein knew little about the Thomas Jefferson School of Law, other than that it was in San Diego, which seemed like a fine place to spend three years.

“I looked at schools in Pennsylvania and Long Island,” he says, “but I thought, why not go somewhere I’ll enjoy?”

Mr. Wallerstein is chatting over lunch one recent afternoon with his fiancée, Karin Michonski. She, too, seems unperturbed by his dizzying collection of i.o.u.’s. Despite those debts, she hopes that he does not wind up in one of those time-gobbling corporate law jobs.

“We like hanging out together,” she says with a laugh.

If love paid the bills, these two would be debt-free tomorrow. But it doesn’t, and Mr. Wallerstein has no money in the bank, no assets and — aside from the occasional job as a legal temp — no wages to garnish. He and Ms. Michonski live rent-free in a nearby brownstone, in return for keeping an eye on the elderly man who owns the place.

“Sometimes the banks will threaten to sue,” he says, “but one of the first things you learn in law school, in civil procedure class, is that it doesn’t make sense to sue someone who doesn’t have anything.”

He remembers little about the promotional materials the Thomas Jefferson school sent when he applied in 2006, other than a pamphlet with lots of promising numbers. That was before the economy crumbled, but the school’s postgraduate data still looks fabulous, particularly given its spot in the fourth and bottom tier of U.S. News’s rankings. The most recent survey says 92 percent of Thomas Jefferson grads were employed nine months after they earned their degrees.

Beth Kransberger, associate dean of student affairs at Thomas Jefferson, stands by that figure, noting that it includes 25 percent of those graduates who could not be located, as well as anyone who went on to other graduate studies — all perfectly kosher under the guidelines.

Like lots of administrators, she defends the figures she gathers and laments that so many other schools are manipulating results.

“You need to take the high road,” she said. “Schools that are behaving the most ethically want students who come to law school with their eyes open.”

Even students with open eyes, though, will have a hard time sleuthing through the U.S. News rankings. They are based entirely on unaudited surveys conducted by each law school, using questions devised by the American Bar Association and the National Association for Law Placement. Given the stakes and given that the figures are not double-checked by an impartial body, each school faces exactly the sort of potential conflict of interest lawyers are trained to howl about.

The surveys themselves have a built-in bias. As many deans acknowledge, the results are skewed because graduates with high-paying jobs are more likely to respond than people earning $9 an hour at Radio Shack. (Those who don’t respond are basically invisible, aside from reducing the overall response rate of the survey.)

Certain definitions in the surveys seem open to abuse. A person is employed after nine months, for instance, if he or she is working on Feb. 15. This is the most competitive category — it counts for about one-seventh of the U.S. News ranking — and in the upper echelons, it’s not unusual to see claims of 99 percent and, in a handful of cases, 100 percent employment rates at nine months.

A number of law schools hire their own graduates, some in hourly temp jobs that, as it turns out, coincide with the magical date. Last year, for instance, Georgetown Law sent an e-mail to alums who were “still seeking employment.” It announced three newly created jobs in admissions, paying $20 an hour. The jobs just happened to start on Feb. 1 and lasted six weeks.

A spokeswoman for the school said that none of these grads were counted as “employed” as a result of these hourly jobs. In a lengthy exchange of e-mails and calls, several different explanations were offered, the oddest of which came from Gihan Fernando, the assistant dean of career services. He said in an interview that Georgetown Law had “lost track” of two of the three alums, even though they were working at the very institution that was looking for them.

As absurd as the rankings might sound, deans ignore them at their peril, and those who guide their schools higher up the U.S. News chart are rewarded with greater alumni donations, better students and jobs at higher-profile schools.

“When I was a candidate for this job,” said Phillip J. Closius, the dean of the University of Baltimore School of Law, “I said ‘I can talk for 10 minutes about the fallacies of the U.S. News rankings,’ but nobody wants to hear about fallacies. There are millions of dollars riding on students’ decisions about where to go to law school, and that creates real institutional pressures.”

Mr. Closius came from the University of Toledo College of Law, where he lifted the school to No. 83 from No. 140, he said. Among his strategies: shifting about 40 students with lower LSAT scores into the part-time program. Because part-time students didn’t then count in the U.S. News survey — the rules have since been changed — Toledo’s bar passage rate rose, which helped its ranking.

“You can call it massaging the data if you want, but I never saw it that way,” he says. Weaker students wound up with lighter course loads, which meant that fewer of them flunked out. In his estimation, a dean who pays attention to the U.S. News rankings isn’t gaming the system; he’s making the school better.

Unfortunately, he says, not all schools play fair.

Of course, fair play is hardly encouraged. Any institution with the guts to report, say, a 4 percent drop in postgraduate employment would plunge in the rankings, leaving the dean to explain a lot of convoluted math, and the case for unvarnished truth, to a bunch of angry students and alums.

Critics of the rankings often cast the issue in moral terms, but the problem, as many professors have noted, is structural. A school that does not aggressively manage its ranking will founder, and because there are no cops on this beat, there is no downside to creative accounting. In such circumstances, the numbers are bound to look cheerier, even as the legal market flat-lines.

“We ought to be doing a better job for our students and spend less time worrying about whether another school is five spots ahead,” says David N. Yellen, dean of the Loyola University Chicago School of Law. “But in the real world you can’t escape from the pressures. We’re all sort of trapped. I don’t know if anyone is out-and-out lying, but I do know that a lot of schools are hyping a lot of misleading statistics.”

WHEN Mr. Wallerstein started at Thomas Jefferson, he was in no mood for austerity. He borrowed so much that before the start of his first semester he nearly put a down payment on a $350,000 two-bedroom, two-bath condo, figuring that the investment would earn a profit by the time he graduated. He was ready to ink the deal until a rep at the mortgage giant Countrywide asked if his employer at the time — a trade magazine publisher in New Jersey — would write a letter falsely stating that he was moving to San Diego for work.

“We were on a three-way call with my real estate agent and I said I didn’t feel comfortable with that,” he says. “The Countrywide guy chuckled and said, ‘Everyone lies on their mortgage application.’ ”

Instead, Mr. Wallerstein rented a spacious apartment. He also spent a month studying in the South of France and a month in Prague — all on borrowed money. There were cost-of-living loans, and tuition of about $33,000 a year. Later came a $15,000 loan to cover months of studying for the bar.

Today, his best guess is that he should be sending $2,000 to $3,000 a month in total, to lenders that include Wells Fargo, Citibank and Sallie Mae.

“There are a bunch of others,” he says. “I’m not really good at keeping records.”

Mr. Wallerstein didn’t know it at the time, but Thomas Jefferson leads the nation’s law schools in at least one category: 95 percent of students graduate with debt, the highest rate in the U.S. News rankings.

The reason, Ms. Kransberger says, is that many Thomas Jefferson students are either immigrants or, like Mr. Wallerstein, the first person in their family to get a law degree; statistically those are both groups with generally little or modest means. When Ms. Kransberger meets applicants engaged in what she calls “magical thinking” about their finances, she advises them to defer for a year or two until they are on stronger footing.

“But I don’t think you can act as a moral educator,” she says. “Should we really be saying to students who don’t have family help, ‘No, you shouldn’t have access to law school’? That’s a tough argument to make.”

It’s an argument complicated by the reality that a small fraction of graduates are still winning the Big Law sweepstakes. Yes, they tend to hail from the finest law schools, and have the highest G.P.A.’s. But still.

“Who’s to say to any particular student, ‘You won’t be the one to get the $160,000-a-year job,’ ” says Steven Greenberger, a dean at the DePaul College of Law. “I think they should have all the info, and the info should be accurate, but saying once they know that they shouldn’t be allowed to come, that’s predicated on the idea that students are really ignorant and don’t know what is best for them.”

Based on the seething and regret you hear from some law school grads, more than a few wish that someone had been patronizing enough to say, “Oh no you don’t.” But it’s often hard to convince students about the potential downside of law school, says Kimber A. Russell, a 37-year-old graduate of DePaul, who writes the Shilling Me Softly blog.

“This idea of exceptionalism — I don’t know if it’s a thing with millennials, or what,” she says, referring to the generation now in its 20s. “Even if you tell them the bottom has fallen out of the legal market, they’re all convinced that none of the bad stuff will happen to them. It’s a serious, life-altering decision, going to law school, and you’re dealing with a lot of naïve students who have never had jobs, never paid real bills.”

Graduates who have been far more vigilant about their finances than Mr. Wallerstein are in trouble. Today, countless J.D.’s are paying their bills with jobs that have nothing do with the law, and they are losing ground on their debt every day. Stories are legion of young lawyers enlisting in the Army or folding pants at Lululemon. Or baby-sitting, like Carly Rosenberg, of the Brooklyn Law School class of 2009.

“I guess I kind of assumed that someone would hook me up with something,” she says. She has sent out 15 to 20 résumés a week since March, when she passed the bar. So far, nothing.

Jason Bohn is earning $33 an hour as a legal temp while strapped to more than $200,000 in loans, a sizable chunk of which he accumulated during his time at Columbia University, where he finished both a J.D. and a master’s degree.

“I grew up a ward of the state of New York, so I don’t have any parents to call for help,” Mr. Bohn says. “For my sanity, I have to think there is an end in sight.”

AS a student, Mr. Wallerstein assumed that the very scale of law school — all the paperwork, all the professors, all the tests — implied that pots of gold awaited anyone with smarts, charm and a willingness to work hard. He began to doubt that assumption when the firm where he had interned told him that it hadn’t been profitable for two years and could not offer him a full-time job.

Mr. Wallerstein and his fiancée moved back East after graduation, and he landed a job at a small firm in Queens. He says he was paid $10 an hour and worked for a manager who seemed to have walked straight out of a Dickens novel. Over a firm-wide lunch, as Labor Day approached, she asked employees to thank her, one at a time, for giving them the holiday off.

“When it was my turn, I said, ‘Labor Day is about celebrating the 40-hour workweek, weekends, that sort of thing,’ ” Mr. Wallerstein recalls. “She said, ‘Well, workers have that now so you don’t need a day off to celebrate it.’ ”

He lasted less than a month.

Since then, he has found jobs at temporary projects reviewing documents.The latest of these gigs is in office space rented on the 11th floor of the Viacom building in Times Square. He sits in a small, windowless room with five other lawyers, all clicking through page after page of documents on computers under fluorescent lights. The walls are bare except for the name of each lawyer, tacked overhead.

“Welcome to the veal pen,” said one during a tour two weeks ago.

The job is set up through a company called Peak Discovery, which put an ad on Craigslist, seeking 100 lawyers. “We got about 300 responses overnight,” said John Thacher, who is managing the project.

Mr. Thacher has managed about 2,500 people in his six years in the temporary legal business, and maybe five of them have gone on to associate jobs in law firms, the kind of work that nearly everyone aspires to when entering law school.

“Most of us either went to the wrong law school, which is the bottom two-thirds, or we were too old when we graduated,” he said. “I was 32 when I graduated, and at 32 you’re washed up in this field, in terms of a shot at the real deal. They perceived me as somebody they can’t indoctrinate into slave labor and work to death for seven years and then release if they don’t like you.”

This gets to what might be the ultimate ugly truth about law school: plenty of those who borrow, study and glad-hand their way into the gated community of Big Law are miserable soon after they move in. The billable-hour business model pins them to their desks and devours their free time.

Hence the cliché: law school is a pie-eating contest where the first prize is more pie.

Law school defenders note that huge swaths of the country lack adequate and affordable access to lawyers, which suggests that the issue here isn’t oversupply so much as maldistribution. But when the numbers are crunched, studies find that most law students need to earn around $65,000 a year to get the upper hand on their debt.

That kind of money is hard to earn hanging a shingle in rural Ohio or in public defenders’ offices, the budgets of which are often being cut. As elusive, and inhospitable, as jobs in Big Law may be, they are one of the few ways for new grads to keep out of delinquency.

The mismatch of student expectations and likely postgraduate outcomes is starting to yield some embarrassing headlines. In October, a student at Boston College Law School made news by posting online an open letter to the dean, offering to leave the school if he could get his tuition money back.

“With fatherhood impending,” wrote the student, whose name was redacted, “I go to bed every night terrified of the thought of trying to provide for my child AND paying off my J.D., and resentful at the thought that I was convinced to go to law school by empty promises of a fulfilling and remunerative career.”

After a few years of warnings by concerned professors, the American Bar Association is now studying whether it should refine the questions in its surveys in order to get more realistic and useful statistics for the U.S. News rankings. In mid-December, the organization held a two-day hearing in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., about the collection of job placement data.

“There is a legitimate question about whether we’re asking for detailed-enough info and displaying that info for those who use it,” says Bucky Askew of the bar association. “I think it’s fair to say we’re aware of the criticism and have a committee working to getting to the bottom of this.”

And what about U.S. News? The editors could, but won’t unilaterally demand better data from law schools. “Do we have the power to do that? Yes, I think we do,” said Robert Morse, who oversees the law school rankings. “But we’d have to create a whole new definition of ‘employed,’ and it would be awkward if U.S. News imposed that definition by itself. It would be preferable if the A.B.A. took a leadership role in this.”

Instead of overhauling the rankings, some professors say, the solution may be to get law schools and the bar association out of the stat-collection business. Steven Greenberger of DePaul recommends a mandatory warning — a bit like the labels on cigarette packs — that every student taking the LSAT, the prelaw standardized test, must read.

“Something like ‘Law school tuition is expensive and here is what the actual cost will be, the job market is uncertain and you should carefully consider whether you want to pursue this degree,’ ” he says. “And it should be made absolutely clear to students, that if they sign up for X amount of debt, their monthly nut will be X in three years.”

Another approach would be to limit class sizes or the number of new law schools. But the bar association, which is granted accrediting authority by the Department of Education, says that it would run afoul of antitrust law if it imposed such limits.

Today, American law schools are like factories that no force has the power to slow down — not even the timeless dictates of supply and demand.

Solving the J.D. overabundance problem, according to Professor Henderson, will have to involve one very drastic measure: a bunch of lower-tier law schools will need to close. But nobody inside of the legal establishment, he predicts, has the stomach for that. “Ultimately,” he says, “some public authority will have to step in because law schools and lawyers are incapable of policing themselves.”

MR. WALLERSTEIN, for his part, is not complaining. Once you throw in the intangibles of having a J.D., he says, he is one of law schools’ satisfied customers.

“It’s a prestige thing,” he says. “I’m an attorney. All of my friends see me as a person they look up to. They understand I’m in a lot of debt, but I’ve done something they feel they could never do and the respect and admiration is important.”

Compared with the life he left four years ago, he has lost ground. That research position in Newark, he figures, would pay him $60,000 a year now, with benefits. Instead, he’s vying with a crowd for jobs that pay at rates just a little higher, but that last only a few weeks at a time, with no benefits. And he’s a quarter-million dollars in the hole.

Unless, somehow, the debt just goes away. Another of Mr. Wallerstein’s techniques for remaining cool in a serious financial pickle: believe that the pickle might somehow disappear.

“Bank bailouts, company bailouts — I don’t know, we’re the generation of bailouts,” he says in a hallway during a break from his Peak Discovery job. “And like, this debt of mine is just sort of, it’s a little illusory. I feel like at some point, I’ll negotiate it away, or they won’t collect it.”

He gives a slight shrug and a smile as he heads back to work. “It could be worse,” he says. “It’s not like they can put me jail.”

Copyright 2011 The New York Times Company. Reprinted from The New York Times, National, of Sunday, January 9, 2011.